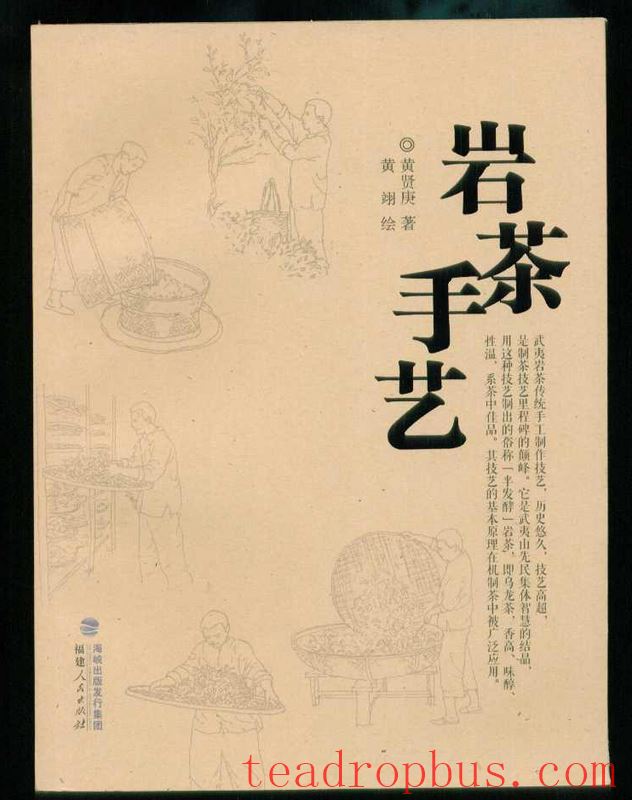

The traditional handmade skills of

Rock Tea

The skills of making Rock Tea have a long history. The process is complex, time-consuming, and labor-intensive, allowing the inherent quality of Rock Tea to be fully expressed. Its fundamental principles are widely applied in today's mechanized production of Wuyi Rock Tea, making it a precious treasure of Chinese culture. In 2025, the traditional handmade skills for making Wuyi Rock Tea (Da Hongpao) were listed as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage.

In light of this, the author, drawing on his own experiences in handcrafting tea since childhood, spent two to three years collecting and organizing information, reminiscing about the past, and compiling a comprehensive and systematic guide on the traditional handmade skills for making Rock Tea, titled “The Art of Rock Tea.” The illustrations in the book are all rendered in line drawings to capture the unique techniques of the tea masters and the tools they used. The book lists 76 complete tea-making skills, 58 workshops and tools, and includes 168 illustrations (including various methods of operation, detailed displays, and parts of tools).

The terms for the processes, techniques, workshops, and tools in Rock Tea handcrafting have their own traditional local dialect names. For example:

Firstly, according to the traditional local dialect names. For instance, “daoqing” (dumping green leaves), “zoushui” (walking water), and “chaoqing” (withering) are called “withering,” “fermentation,” and “fixation” respectively in academic terms; the sieves used for withering and shaking the tea are called “shuisai” (water sieve), which implies their role in “zoushui” (walking water); the window through which tea is passed into the Roasting room is called “mamen” (horse door). The fuel known academically as “mangqigu” is called “jimeng” or “langyi”; small shrubs and branches are referred to as “chaizi” and “qiutiao,” and so forth.

Secondly, the specifications of tea-making tools follow traditional designs. Since these tools were handmade in the past, their sizes varied from factory to factory but were generally smaller compared to modern ones, making them more lightweight and flexible. For example, the water sieve and tea sifting basket had greater elasticity.

The traditional skills for making Wuyi Rock Tea are indeed advanced and challenging. For example, “kaiqing” (spreading out the green leaves). This involves evenly spreading out the green leaves for uniform exposure to sunlight. It is a highly skilled technique. Techniques include using a rice sieve, an axe, or pushing and pulling. Using a rice sieve is considered the best. During kaiqing, an assistant holds the tea leaves, placing them in the water sieve, while the master quickly spreads them out. The technique involves gently lifting the tea leaves slightly off the sieve and then rotating the sieve at the moment the tea leaves are in mid-air, allowing them to fall evenly back onto the sieve. Not only must it be done quickly, but also uniformly. Although it seems like a simple movement, some people spend their entire lives without mastering it. Can you imagine how difficult it is?

For example, “shaqing” (shaking the tea leaves). When shaking the tea leaves, one must keep the back straight, grasping the frame of the water sieve at one-third its length, shaking it left and right in alternating high and low movements. This causes the tea leaves to rise in a spiral shape, promoting “zoushui” (walking water) through their collision with each other. For the first shake, just a few gentle shakes are needed, gradually increasing the number of shakes and the duration as needed later on.

For example, “chaoqing” (fixation). The primary purpose of fixation is to set the quality developed during the withering stage. The temperature in the Wok for chaoqing exceeds 200 degrees Celsius, requiring the master to perform manual operations under high heat, which is very arduous. During fixation, about 1 kilogram of tea leaves is placed in the wok. The worker uses their hands to press down on the tea leaves, dragging them towards the front before flipping them over. This cycle is repeated, typically for about 2 to 3 minutes. However, the duration of fixation depends on the age, moisture content, and variety of the tea leaves. If the tea leaves contain more moisture, they should be lifted and scattered before being flipped over again.

For example, “roucha” (rolling the tea leaves). The purpose of rolling the tea leaves is to form a gel-like substance from the effective elements within the leaves and transfer it to the surface, while also curling the leaves into twisted strands.

When rolling the tea leaves, the feet are positioned in a horse stance, leaning forward slightly. The left hand holds the tea leaves, while the right hand presses down on them and pushes them forward. As the tea leaves reach the front of the rolling tool, the right hand grips them and gently pulls them back, and the left hand pushes them forward to the right. This process is repeated, alternating between the two hands. Rolling and fixing the tea leaves are sequential tasks that require continuous and swift movements to ensure the smooth progress of the process.

For example, “bocha” (sifting the tea leaves). The purpose of sifting the tea leaves is to remove triangular pieces, dust, and broken leaves. To do this, stand with your feet apart, lean slightly forward, and grasp the sides of the sifting basket at two-fifths its length, resting the back end against your navel. The technique involves lifting the tea leaves in the basket and slightly tilting it backward, causing the lighter pieces and dust to float to the front of the basket. By straightening the abdomen, the pieces and dust are shaken out. The force used when sifting depends on the amount of pieces and dust present.

Speaking of “zuqing” (green processing), it is even more challenging. “Watching the tea to process it” and “processing the tea according to the weather” seem to be secrets, but they actually have scientific reasoning behind them. Not only must one know how to observe, but also how to act accordingly. Observation is to understand the principles, while action is to facilitate change, making the tea leaves go through a process of “living and dying” and then “reviving.” In simpler terms, one needs to know how to promote changes in the green leaves while also inhibiting those changes, knowing when to stop. This is why Wuyi Rock Tea has “vitality,” and its “vitality” comes from the skills and “insight” of the tea maker. This is a ten-hour task that requires great attention to detail. In the old days, teachers often kept their knowledge to themselves, fearing that “teaching the apprentice would lead to the master's downfall.” Therefore, they would instruct their apprentices on what to do but never explain why. Unless the apprentice was their own child or grandchild. Thus, there was a saying: “Learning the