The appropriate degree of bleaching is the foundation for high-quality bleached Tea. Within a certain range, the whiter the fresh leaves, the higher their amino acid content and sensory quality; however, exceeding a certain degree of bleaching can lead to a decrease in internal substances, causing a corresponding decline in tea quality, making it less fragrant and bland; when the degree of bleaching is insufficient, the tea quality shifts towards that of conventional tea, failing to display the inherent characteristics of bleached tea. Therefore, controlling a reasonable degree of bleaching is the key technology for producing high-quality fresh Leaf raw materials.

I. Bleaching Expression Factors

(A) Ecological Conditions

The decisive ecological factor for the expression of bleaching in low-temperature-sensitive bleached tea is a certain low-temperature condition, followed by soil type and nutrient supply. Light and tree vigor also play an auxiliary role in bleaching.

1. Temperature

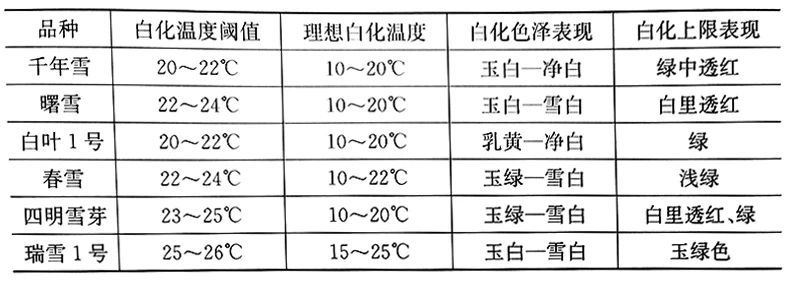

Studies have shown that the dependence on temperature, from strongest to weakest, is in the order of Qian Nian Xue (Thousand Year Snow), Bai Ye No.1, and Si Ming Xue Ya (Four Bright Snow Bud). The dependence of the parent varieties is stronger than that of their offspring.

Temperature dependence of spring shoot bleaching in low-temperature-sensitive bleached tea

2. Soil Type and Nutrition

Studies have found that the most sensitive variety to soil type and nutrition is Bai Ye No.1 and Qian Nian Xue, while the dependency is relatively less obvious in varieties like Si Ming Xue Ya. Under the same cultivation measures, tea gardens with clayey soil are less likely to bleach or more prone to regreening, while those with sandy soil show more obvious bleaching. In tea gardens with sufficient fertility, especially with abundant nitrogen fertilizer, bleaching is not obvious, whereas in gardens with insufficient fertility, bleaching is very apparent.

3. Other External Factors

The dependence of low-temperature-sensitive bleaching on light is not as strong as that of light-sensitive bleached tea, but within a suitable temperature range for bleaching, light can cause differences in the degree of bleaching. At relatively high temperatures, moderately reducing light can increase the bleaching expression of Bai Ye No.1, while there seems to be little impact on Qian Nian Xue and Si Ming Xue Ya; when the tree itself has vigorous growth, the new shoots receive more nutrients, and the degree of bleaching decreases accordingly.

(B) Flush Period and Bleaching Expression

Under natural conditions, except for Qian Nian Xue occasionally showing bleaching during autumn when encountering low temperatures, other varieties (strains) only exhibit bleaching in the spring flush; there is often a significant difference between the bleaching expression of buds and leaves in the early part of the Spring Tea season and later parts. Generally, the degree of bleaching in the later period is higher than in the earlier period, with leaf-bleached types of bleached tea being particularly evident.

Within a suitable temperature range for bleaching, the buds and leaves of leaf-bleached types of bleached tea usually undergo a bleaching initiation process during the early part of the spring tea season. Before the first leaf is fully developed, the buds and leaves of Bai Ye No.1 are typically creamy yellow or jade green, while Qian Nian Xue is jade green or light green; the transition to white occurs during the initial development of the first leaf to the initial unfolding of the second leaf, sometimes with a sudden whitening observed within a day.

Similarly, within a suitable temperature range for bleaching, the bleaching of later flushes often lacks a clear bleaching initiation process, and the bleaching is very direct. Bai Ye No.1 exhibits a green stem and white leaf state from the beginning of leaf development, with the degree of leaf bleaching resembling snow. When the temperature drops below 15°C, the bleached buds and leaves exhibit obvious inferior qualities, becoming narrow and ribbon-like, with hard stems and thin leaves, leading to a decline in quality.

(C) Shoot Vigor and Bleaching Expression

The issue of differences in the vigor or quality of buds and leaves between early and later flushes is relatively common in conventional varieties, such as Ping Yang Te Zao Cha (Pingyang Special Early) and Zhe Nong 139, where the buds and leaves in the early period are relatively robust, while the tea buds appear very thin and small in the later period. For low-temperature-sensitive bleached tea, the bleaching phenomenon is very noticeable when the temperature is low, and the growth of the buds and leaves is suppressed; when the temperature is high, no bleaching occurs or it is not obvious, and the growth of the shoots improves.

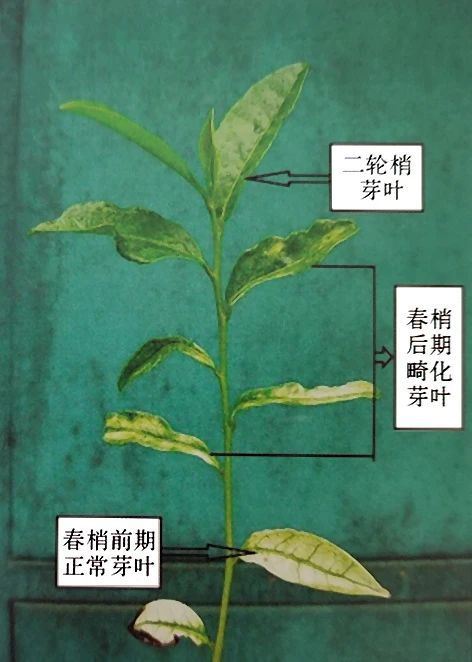

Studies on the mechanism of bleaching have shown that the bleaching of buds and leaves leads to an obstruction in chlorophyll synthesis, which in turn affects the growth vigor of the shoots. Overall, the growth vigor of bleached shoots is weaker than that of unbleached branches, with thinner and smaller leaves, a decrease in the number of unfolded leaves, and shorter shoot lengths. The higher the degree of bleaching, the poorer the growth vigor of the shoots. Shoots that remain highly bleached often stop growing after developing two or three leaves, accompanied by inferior qualities and physiological disorders. Highly bleached shoots gradually return to normal leaf shape and growth vigor only after the next flush of shoots emerges.

Morphology of Development of Highly Bleached Shoots

II. Appropriate Degree of Bleaching

The appropriate degree of bleaching refers to the degree of bleaching that meets the requirements for high-quality fresh leaves of bleached tea while maintaining normal growth and development of the shoots.

Since the picking standards for fresh leaves of bleached tea generally include single bud, one bud and one leaf, and one bud and two leaves, for the appropriate degree of bleaching required for high-quality fresh leaves, if bleaching only appears when the tenderness of the fresh leaves is lower than the two-leaf standard, it loses practical significance; for the tree vigor, the lack of bleaching or rapid regreening of the buds and leaves after the second leaf is more conducive to subsequent growth. Therefore, the focus of production regulation for the appropriate degree of bleaching is the regulation of bleaching within the two-leaf period.

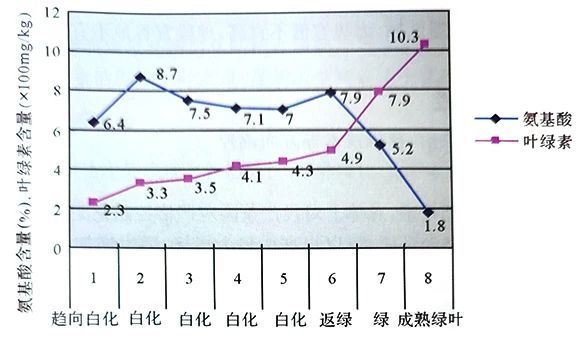

The changes in levels of chlorophyll, amino acids, etc., in Bai Ye No.1 from the onset of bleaching, through bleaching, regreening to mature green leaves, correspond to the tenderness of the buds and leaves picked, which are one leaf initially unfolded (onset of bleaching), one leaf unfolded to two leaves unfolded (bleaching), and maintenance of two leaves unfolded (green) standards. It can be seen that before regreening, the color of the buds and leaves tends from bleaching to a bleached state, and the change in chlorophyll levels is a gradual accumulation process, while amino acids maintain relatively high levels overall, forming a saddle-shaped dynamic curve. The degree of bleaching of the fresh leaves during this stage is relatively appropriate.

Degree of Bleaching and Levels of Amino Acids, Chlorophyll

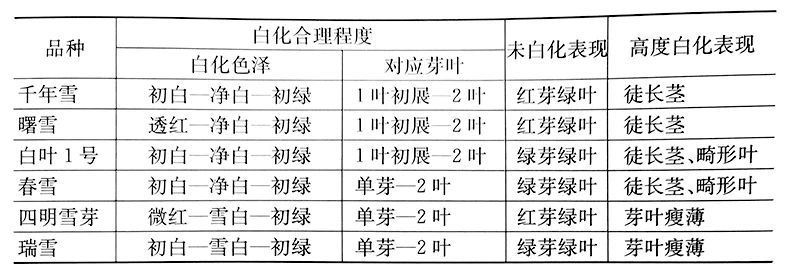

Under suitable temperature conditions, there are significant differences in the bleaching of buds and leaves among different varieties, and familiarity with their bleaching patterns helps to grasp the appropriate degree of bleaching.

Appropriate degree of bleaching within the picking standards of bleached tea

III. Regulatory Measures

The regulation of an appropriate degree of bleaching involves bidirectional regulation, but since tea trees are cultivated under natural conditions, the measures for regulating the appropriate indicators of bleaching are often difficult to implement. Relatively speaking, regulation towards greening is easier than regulation towards bleaching.

(A) Fundamental Regulation

This mainly refers to the selection of planting areas, sections, and soil types when establishing tea gardens. In southern regions with high accumulated temperatures, the altitude should be higher rather than lower, sections should be mountainous rather than flat, and the soil should be sandy rather than clayey; in northern regions with low accumulated temperatures, the