The term “zhan,” seldom mentioned these days, is much like the object it represents, no longer used in everyday life. According to the dictionary: a zhan is a small, shallow bowl.

So what is Jian ware?

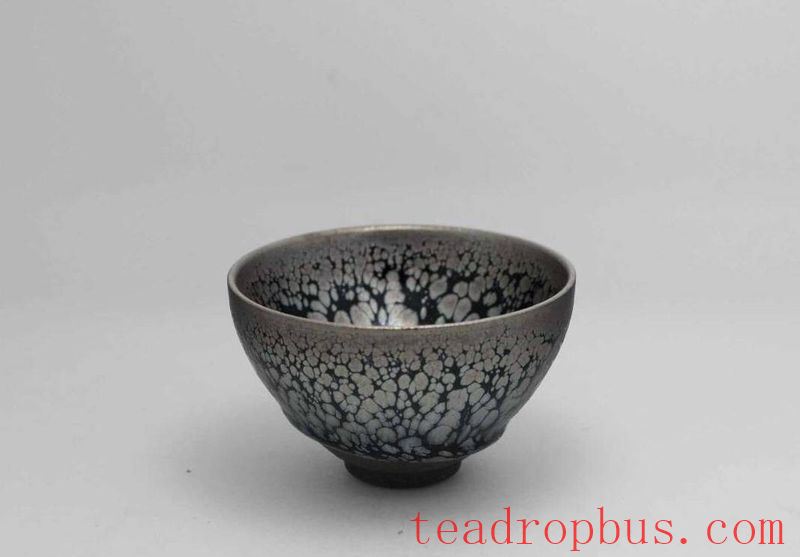

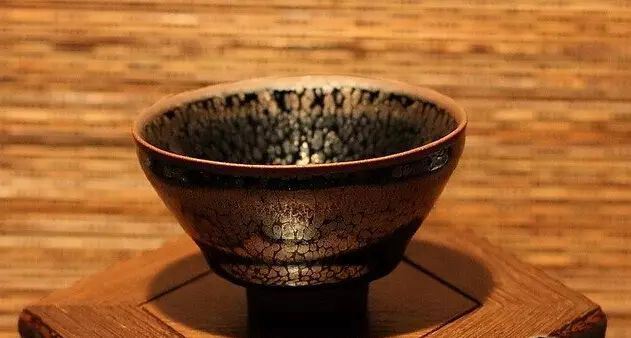

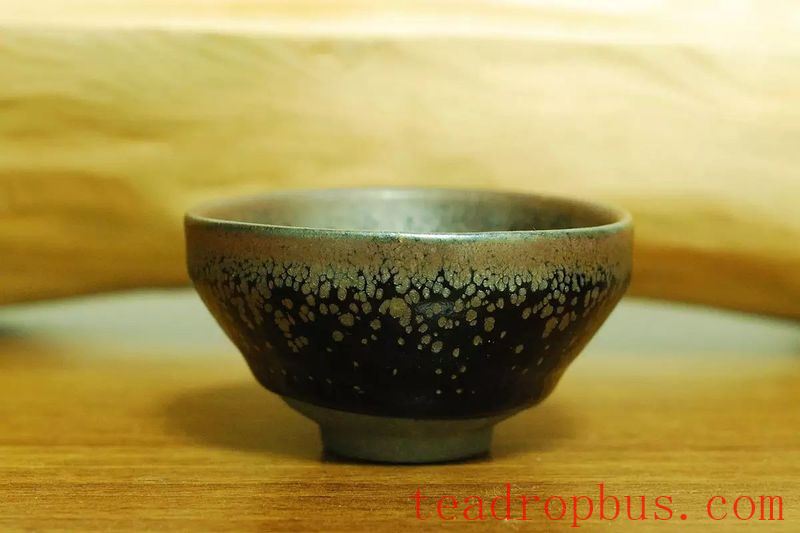

Jian ware specifically refers to porcelain Tea bowls produced in the kilns of Jianyang, Fujian Province. Generally speaking, these bowls have wide mouths and narrow feet, with thick, coarse bodies. The exterior lower part of the bowl and the foot are unglazed, exposing the body of the bowl.

The clay and glaze for Jian ware come from its place of origin, Jianyang. Due to their high iron content and the thickness of the clay, the exposed body appears grayish-black, commonly referred to as an iron body. The glaze colors range from deep black, dark blue-black, to purple. At the high temperature of 1350 degrees Celsius reached in the kiln during firing, iron ions precipitate out and flow across the glaze surface, forming unique and beautiful patterns known as “hare's fur,” making the Jian ware bowls more widely recognized by this name.

The Chinese civilization is the only ancient culture that has been continuously passed down in an orderly manner and remains vibrant to this day. However, countless ancient wisdoms have been lost throughout history. Among those that have been rediscovered, Jian ware kiln tea bowls are one such example.

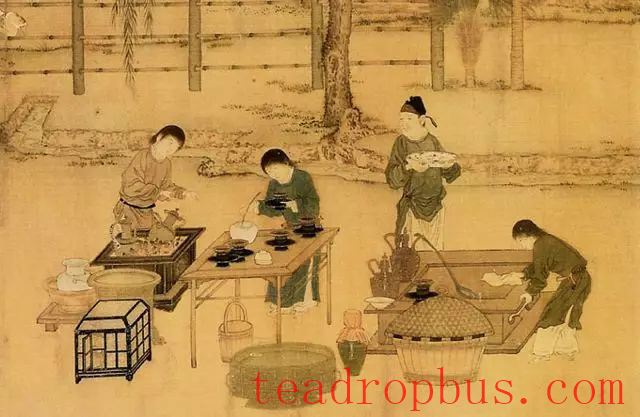

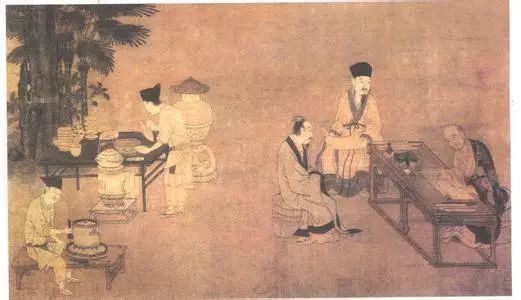

The heyday of Jian ware was during the Song Dynasty. Throughout both Northern and Southern Song periods, Jian ware bowls were considered the pinnacle of tea-drinking utensils, sought after by the nobility and gentry, and admired by literati and scholars. However, the renewed interest in Jian ware among modern people is a recent phenomenon, within the past decade. If enthusiasts of ceramics were to consult sources from the Ming and Qing dynasties, they would find little information on Jian ware, and what little there is, is vague and fragmentary. In fact, starting from the Yuan dynasty, the Jian kilns gradually became less active, and by the Ming and Qing periods, they were almost entirely forgotten. What caused this? Let us first look at a passage from the Northern Song's “Record of a Banquet at Taiqing Pavilion” to understand the zenith of Jian ware.

In the second year of the Zhenghe era (Northern Song), the capital Bianliang enjoyed a warm spring. Inside the palace grounds at Taiqing Pavilion's Chigong Hall, Emperor Huizong hosted a banquet for Chancellor Cai Jing. Precious wine jars, treasures, glass, agate, crystal, jade, and other valuables were arrayed before them…

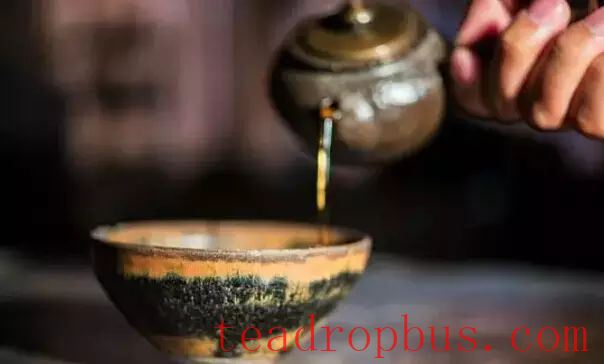

After drinking, Emperor Huizong personally prepared tea. For tea preparation, he used only clear spring water, a Jian ware bowl, and several cakes of compressed tea. This simplicity seemed somewhat incongruous with the surroundings, but guest Cai Jing was delighted. He was familiar with the elegant tea ceremony and all the utensils involved. The clear spring water came from the stone springs near Huishan Temple, located 1,500 miles from the capital, making it difficult to obtain. The dark blue-Black Tea bowl and the compressed tea cakes came from Cai Jing's hometown, Jianxi. The glaze color of Jian ware is a deep blue-black, resembling a congealed sea, shimmering with reflected light yet deep and dignified.

What is so special about this small, dark bowl? Even with patterns resembling hare's fur, it still seems short and crude, how could it be suitable for refined settings? In fact, Jian ware appears dull at first glance, but upon closer inspection, one discovers that the dark blue-black glaze shines like inkstone, and the patterns are lively, resembling hare's fur, Silver moss, stars, or mountains and seas, captivating and thought-provoking. Only through deeper appreciation can one uncover its splendor.

Song people would admire Jian ware under sunlight, tilting it to see the mesmerizing patterns clearly. Nowadays, we can use magnifying glasses to easily enter the splendid world of Jian ware, though we may feel dizzy and dazzled after lingering too long. The beauty of Jian ware is quiet and unassuming. It lacks the flamboyance of vivid colors or tumultuous waves. Initially unattractive, it simply remains there, like a maiden in repose, waiting for someone who appreciates its beauty to become immersed. Connoisseurs know that while much labor goes into creating such beauty, the key lies in nature's work. Truly beautiful objects are often one in ten thousand, and masterpieces like the iridescent and variant hare's fur patterns can only be bestowed by the gods of the kiln. It is no wonder that even an elegant emperor like Huizong cherished them like pearls and jade.

A great kiln producing only one type of ware—this was the Jian kiln (though not exclusively, as it also produced mundane items like oil lamps, which can be ignored compared to Jian ware bowls). The Jian kiln primarily produced black-glazed tea bowls. Despite the single type of black-glazed Tea bowl, under the combined effects of human skill and natural ingenuity, they transformed into myriad colors and infinite beauty, becoming powerful tools for tea competitions and treasured in their time. They were favored by royalty and inspired many other kilns to imitate them. Two-thirds of kilns across the country produced black-glazed tea bowls. Northern kilns like Ding, Cizhou, and Yaozhou, as well as Southern kilns like Jizhou and other kilns in Fujian, all made similar products, using various methods to imitate hare's fur and oil droplet patterns. However, the beauty of Jian ware remained unparalleled. Various spotted black-glazed bowls produced by the Jian kiln were always cherished by tea enthusiasts. Su Dongpo wrote in “Sending off Nanping Qianshi”: “The monk came out of Nanping Mountain early in the morning, demonstrating his mastery of tea preparation. Suddenly, I saw the hare's fur spots on the tea bowl, and the tea was like spring wine.” Here, Dongpo used a hare's fur-spotted bowl, speculated to be an early Jian ware bowl, with finer spots that had not yet reached the standard of hare's fur. But when paired with the pale Green Tea, it was enough to fill one with the joy of spring with just one sip.

Jian ware may seem ordinary, but it is simple without being monotonous, plain without being crude. Its glaze is deep and lustrous, suitable for tea preparation and competition. The patterns are simple and harmonious, yet varied and numerous, with various renowned types. Especially the iridescent spots resemble a dreamy cosmic sky, with blue light shimmering, inducing endless contemplation and enchantment. Two iridescent bowls later flowed to Japan, where they were obtained by the Japanese warlord Oda Nobunaga, who cherished them like precious gems. Legend has it that one was destroyed during the Incident at Honnō