The History of Wuyi Rock Tea Making Techniques: A Character Worth a Thousand Coins

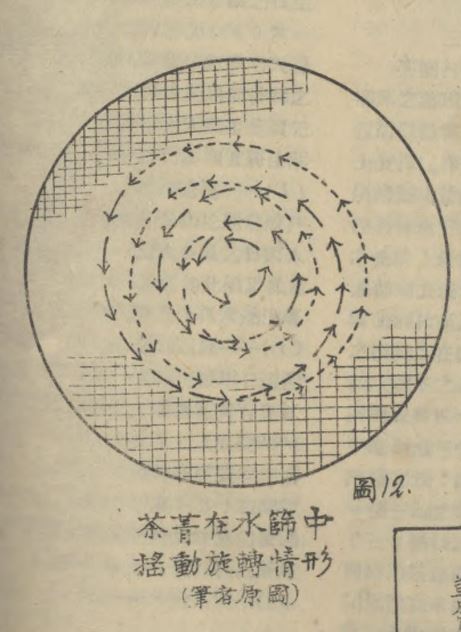

Shaking the green, one of the key procedures in traditional Wuyi Rock Tea making techniques, involves standing straight with feet shoulder-width apart. Hold the bottom third of the water sieve with both hands and tilt the surface slightly inward. Simultaneously apply force to make a back-and-forth motion, pulling and pushing the sieve, causing it to move up and down. The tea leaves on the sieve will start to rotate and roll in a semi-spherical shape. The collision and friction between the leaves and the sieve surface cause damage to the edge cells of the leaves, promoting partial oxidation.

From a physical practice perspective, mastering the shaking of the green has a certain level of difficulty. Lin Fuquan during the Republic of China era wrote, “I continued to learn this step for four days and nights, but my movements still did not meet the requirements. It is said that one must practice continuously for three or four months to become proficient.”

Shaking the green is a point of innovation in the history of Wuyi Rock Tea making techniques. Its emergence and historical path of improvement are worth noting. Let's start with the early records – the character “lù.”

I. A Character Worth a Thousand Coins

The earliest record of the “shaking the green” technique can be found in Lu Tingcan's “Supplement to the Classic of Tea,” which quotes Wang Caotang's “Tea Discourse”:

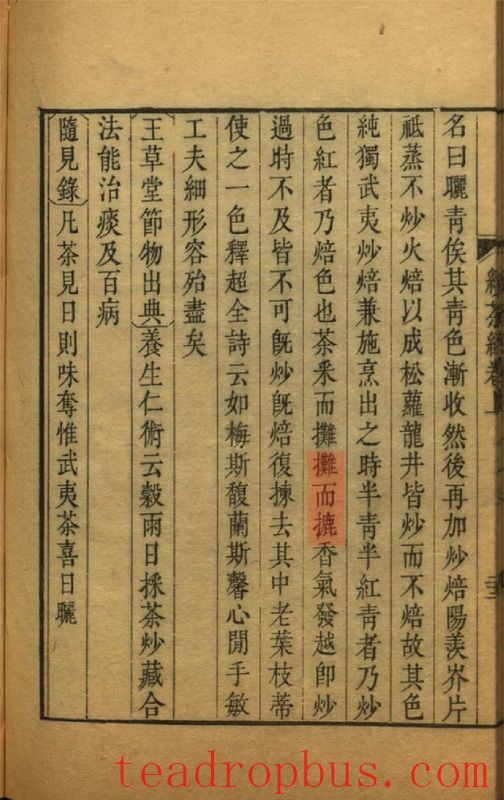

After tea is picked, it is evenly spread in a bamboo basket and placed in the wind and sun, known as sunning. Wait until the green color gradually fades, and then proceed with stir-frying and baking. Yangxian and Jiaopian teas are only steamed, not stir-fried, and fire-baked to completion. Songluo and Longjing are stir-fried but not baked, hence their pure color. Only Wuyi employs both stir-frying and baking. When brewed, the tea is half green and half red, the green part is from stir-frying, and the red part is from baking. After picking, the tea is spread out, shaken, and when its aroma develops, it is stir-fried. Stir-frying too soon or too late is not appropriate. After stir-frying and baking, the old leaves and stems are removed to ensure uniformity.

Wang Caotang, also known by his courtesy name Caotang, was a native of Qiantang (Zhejiang) who lived in Wuyi Mountain. He authored works such as “Wuyi Nine-Curve Records” and “Family Rites Defined.” The “Tea Discourse” cited in “Supplement to the Classic of Tea” is now lost, so we cannot understand its full content. Fortunately, Lu Tingcan's “Supplement to the Classic of Tea” preserves several fragments of it. The quoted passage above is particularly valuable, recording the initial appearance of Wuyi Rock Tea making techniques.

The “lù” in “spread and lù” originally means “vibration, shaking.” According to the “Cihai”: “Lù: shake.” The “Guangyun”: “Lù, pronounced ‘lùgǔ,' meaning ‘shake.'” The “Jiyun”: “Lù, pronounced ‘lùgòng,' meaning ‘shake.'” In “The Rituals of the Zhou Dynasty,” it says, “Three drumbeats, lù the gong, all officials lower their flags, and the chariots and foot soldiers sit down.” According to Han dynasty scholar Zheng Xuan's commentary, “Covering and shaking is lù. Lù stops movement and calms the breath.” Thus, the origin of the character “lù” dates back to “The Rituals of the Zhou Dynasty” and is widely recorded in ancient Chinese dictionaries.

In Wang Caotang's “Tea Discourse,” “lù” refers to shaking the green, a crucial process for partially fermented teas that produces the green Leaf with a red rim. Although it is described with just a single character without specific details about the technique, it is invaluable for tracing the origins and studying the history of Wuyi Rock Tea making techniques.

II. The Unique Origin of the Character “Lù” and Wang Caotang

There are differing opinions in academic circles about whether “spread and lù” records the shaking of the green. Some scholars believe that “lù” in this context means kneading. From a linguistic standpoint, “lù” unambiguously means vibration and shaking, but by examining the background of Wang Caotang, we may further confirm the true meaning of “lù” in “spread and lù.”

(I) “Lù” in “Spread and Lù” Does Not Mean “Knead”

Huang Yisheng's book “Research on the Making Process of Wuyi Rock Tea (Da Hongpao)” argues:

Regarding the interpretation of the ancient character “lù.” In “Tea Discourse,” the “lù” in “picked and spread, spread and lù” is interpreted by those advocating the Oolong tea origin theory as meaning “shake,” which they further extend to mean the green-making process. This is a subjective misinterpretation. In fact, “lù” is a dialectical substitute for “knead” in Wuyi Mountain. Interpreting “lù” as “knead” is based on factual evidence. Ming dynasty scholar Xie Zhaozhe (1567-1624) wrote in “Tea Record”: “Kneading and baking began in our dynasty.” Kneading was part of tea production during the Ming and Qing dynasties, a historical fact.

From a linguistic perspective, there are no examples of “lù” being used as a dialectical substitute for “knead.” Moreover, the material provided by author Xie Zhaozhe merely indicates that kneading was a procedure in tea production during the Ming and Qing dynasties and does not prove a direct relationship between “lù” and “knead.” While the pronunciation of “lù” and “knead” may be similar in the Wu dialect, forcibly interpreting “lù” as “knead” is actually a subjective misinterpretation.

(II) The Unique Origin of “Lù” and Wang Caotang

“Lù” is not a commonly used character. For example, it first appears in “The Rituals of the Zhou Dynasty,” a Confucian classic. Why did Wang Caotang use such a relatively obscure character to describe shaking the green instead of simply using “shake”? In fact, there is a unique connection here.

Although “lù” is almost unused in modern Chinese today, it is commonly used in Wu dialects. For instance, in Xiangshan, Ningbo, “lù” is still used to mean “vibration, shaking,” such as “shake it and see, there's something inside.” There is a toy that northerners call a “rattle drum,” which people in Xiangshan call “lù lù.” Wang Caotang wrote “Family Rites Defined” and would have been familiar with the ritual literature “The Rituals of the Zhou Dynasty.” Additionally, he was from Yuhang, Zhejiang, where the Wu dialect is spoken, so the character “lù” would not have been unfamiliar to him. Therefore, when he encountered the process of shaking the green, using the character “lù” to describe it is not surprising. It is a unique mark of the author in this early record of Wuyi Rock Tea making techniques.

If there is any infringement, please contact us for deletion.