This year, new Pu'er teas are gradually entering the market, and many Tea enthusiasts have started to focus on the topic of how to select their ideal Pu'er tea. I've touched on this before, but today I'll delve into it from a more professional perspective.

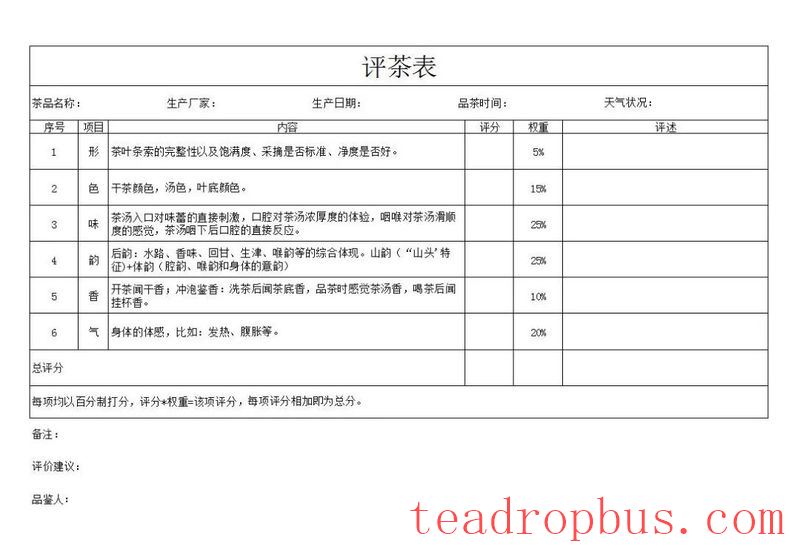

Do you remember the Pu'er tea evaluation chart that I shared with you previously? The chart lists six key factors that influence the quality of Pu'er tea: appearance, color, taste, character, aroma, and qi. I will go into detail about how to use these six factors as criteria for selecting your ideal Pu'er tea.

Appearance

Appearance refers to the shape of the tea leaves, which we often refer to as the twist. Try to choose teas with a high degree of completeness in the twists, looking relatively full-bodied. Fullness is difficult to control, and some articles suggest that thicker twists indicate better quality, which is rather one-sided. Whether twists are thick or not depends on the variety of the tea, picking, and production methods. For example: teas from the Yi Wu, Bang Dong, and Jing Mai regions, especially spring teas, do not have large leaves. If picked according to standards and rolled with moderate pressure, the dried tea won't appear particularly thick. On the other hand, teas with a stronger bitterness from the Lao Banzhang and Lao Man'e areas in the Bulang region are rolled more loosely during production, resulting in thicker-looking dried tea. Therefore, using thickness to describe tea quality isn't very appropriate; using fullness is easier to understand – the tea twists should look neither thin nor shriveled, but rather solid.

Additionally, check if the picking was done according to standards, with about 70-80% being one bud and two leaves, and 20-30% being one bud and three leaves. The fewer impurities in the tea, such as husks and stems, the better.

Color

The term “color” here has three layers of meaning: the color of the dried tea, the color of the brewed tea, and the color of the infused leaves.

The color of dried Pu'er tea can vary depending on the region, with some being darker and others lighter, some more blackish and others more whitish. For instance: the color of dried tea from the Yi Wu area tends to be deeper and slightly blackish, with finer and fewer buds; the color of dried tea from the Bulang Mountain area is lighter or more whitish, with coarser and more abundant buds; Xi Gui tea has an even deeper and blacker color, with fewer buds, while Na Han tea from the same region is lighter and more whitish. These variations in color are relative concepts, and it's difficult to describe them accurately with words; you need to observe and summarize them yourself.

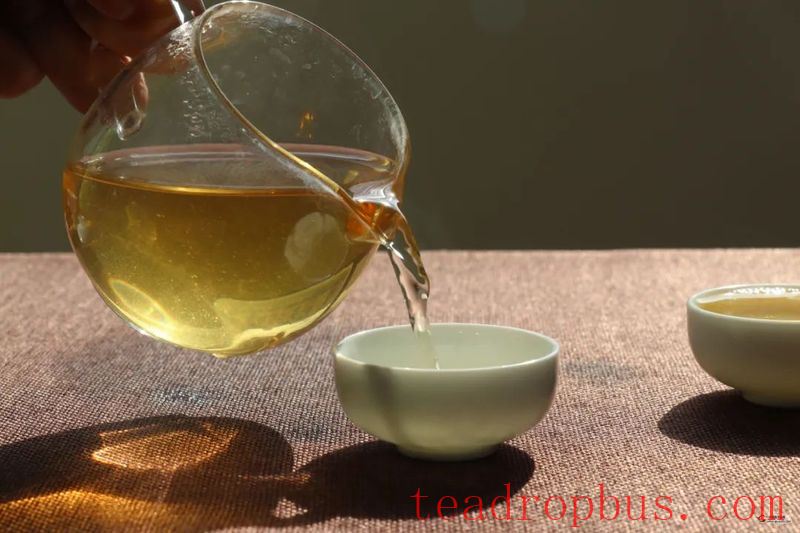

The color of the tea liquor in new teas should ideally be yellow-green. Colors that are too yellow or too green are not desirable; overly yellow indicates the tea has been suffocated or improperly processed, while overly green suggests excessive processing or slight roasting. There's no need to be overly concerned about the clarity of the tea liquor; new teas, especially loose teas, typically don't have great clarity and may contain some fine suspended particles, which is normal.

The color of the infused leaves after brewing six to seven infusions should be yellow, with most of the leaves showing consistent color. Occasionally, a small number of red stems or red leaves, or one or two older leaves appearing green or bluish, are relatively normal. However, if there are too many, it indicates a problem with the tea's production process.