Spanning millennia and thousands of miles

The Tea Horse Road

is currently the highest, most dangerous, longest,

and still-traveled ancient path in the world.

Located on the southwestern frontier of China in Yunnan,

ninety percent of its area is mountainous.

In an era without airplanes, high-speed trains, or expressways,

how was the over ten-thousand-kilometer-long Tea Horse Road traversed through human and horse transport?

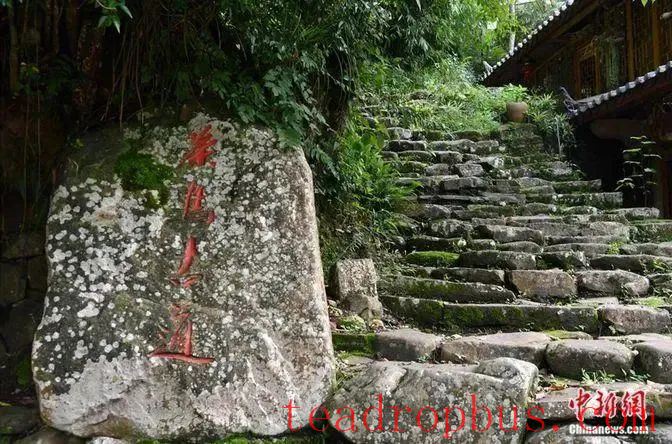

The stone slabs on the Tea Horse Road are weathered with age.

“How beautiful is the Black Tea, how distinct the Tibetan horses…

Tibetan horses for Yellow Tea, seeking gold and pearls from nomadic horses.”

Tea-horse trade fairs

flourished during the Tang and Song dynasties and reached their peak during the Ming and Qing dynasties.

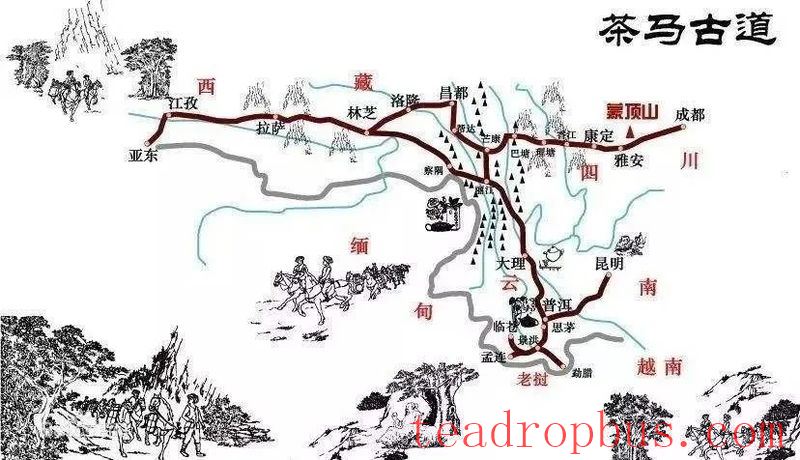

A map of the Tea Horse Road routes. Source: Yunnan Release

Due to “one tea and one horse,”

“a road” was formed.

Although named as a “road,”

over a thousand years of development,

the Tea Horse Road has become a vast network

that spans in all directions and connects mountains and seas.

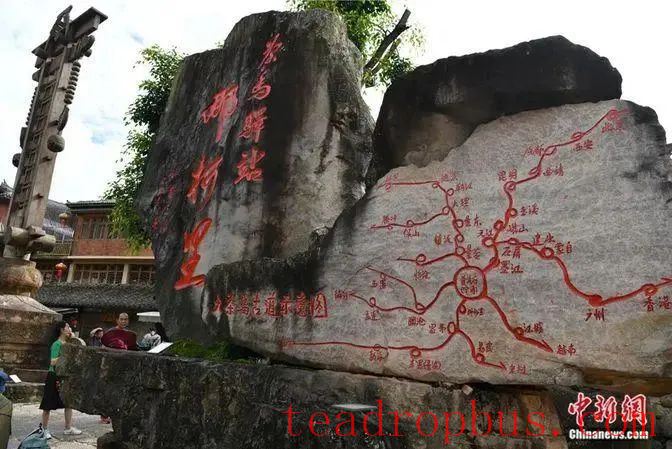

Nakeli was the first station on the southern route of the ancient Pu'er Prefecture's Tea Horse Road.

Its scope can be divided into three areas: core, main trunk, and periphery.

The core area is the border region of Yunnan, Tibet, and Sichuan provinces.

The main trunk area encompasses these three provinces.

The peripheral area includes China's Guizhou, Chongqing, Guangxi, Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, Shaanxi, and other provinces,

as well as extending to Southeast Asian countries like Myanmar, Vietnam, Laos, Thailand,

and South Asian countries such as India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan,

reaching even into Europe.

Yang Haichao, a master's thesis supervisor at the College of Humanities and Law of Southwest Forestry University and deputy director of the Yunnan Tea Horse Road Research Base,

recently introduced in an exclusive interview with China News Service that according to historical records,

in 138 BC, Zhang Qian, on his mission to the Western Regions,

saw Qiong bamboo and Sichuan cloth in Daya (Bactria),

and after inquiry, speculated that there was a commercial route from Yunnan and Sichuan to Shendu (India).

The main urban area of Kunming's Shuncheng Street

was a gathering place for caravans along the Southern Silk Road and the Tea Horse Road during the Ming and Qing dynasties.

In the late Qing dynasty, French officials stationed in China photographed images of escort caravans resting here.

Photographs taken by the late Qing dynasty French official Paul Favier show escort caravans passing through Shuncheng Street. Source: Xinhua News Agency courtesy of Yin Xiaojun

Since the late 19th century,

European explorers, missionaries, and others have collected and published accounts

of their experiences related to the Tea Horse Road in China, Southeast Asia, and South Asia.

The American-Austrian explorer Joseph Rock's

“The Ancient Kingdom of Naxi in Southwest China”

documents part of the caravan routes.

Peter Gou, a Russian, wrote

“The Forgotten Kingdom: Lijiang 1941-1949”

about his experience following caravans to Lijiang.

American writer Edgar Snow recorded his journey following caravans through western Yunnan,

entering Myanmar from Yunnan in “Caravan Travel,”

where he described Kunming as both the end of a railway and the starting point of many caravan journeys,

both the last contact point between East and West and the earliest contact point between East and West.

During World War II,

the Tea Horse Road in Yunnan became an extremely important international commercial route in southwestern China.

At that time, the Burma Road and the Yunnan-Vietnam Railway, which were called the “artery” and “lifeline” by the Chinese,

were bombed and blockaded by Japanese forces.

In times of war, caravans never ceased their journeys,

with bells ringing through the mountains.

The British photographer Mike Freeman captured a rock-cut section of the Tea Horse Road near the town of Bingzhongluo in Gongshan, Yunnan.

Since the 1980s,

Chinese scholars, analogizing to the “Silk Road,”

have referred to the ancient route running through Sichuan, Yunnan, Burma, and India as the “Southwest Silk Road” or “Southern Silk Road.”

In July 1990,

scholars Mu Jihong, Chen Baoya, Li Xu, Xu Yongtao, Wang Xiaosong, Li Lin, and others from Yunnan

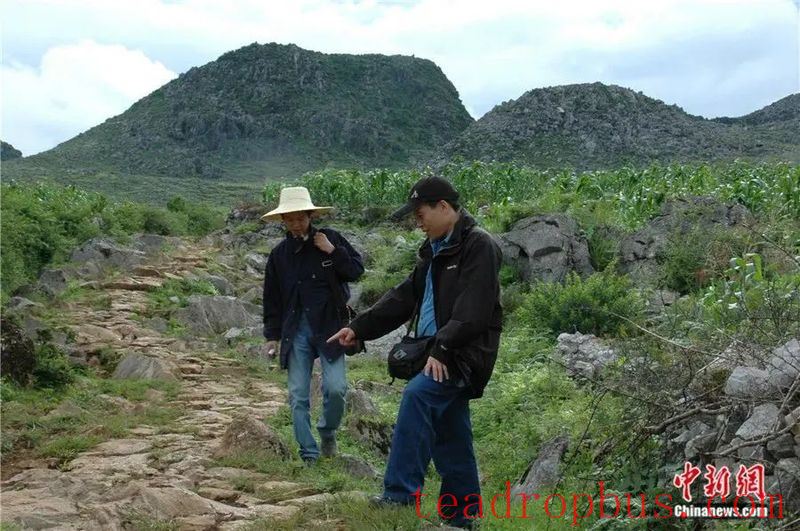

hiked the ancient route used by caravans entering Tibet,

later naming it the “Tea Horse Road.”

Around 2004,

“Tea Horse Road” began to appear frequently in academic literature.

In 2005, Yang Haichao (left) and Chen Baoya explored the Tea Horse Road. Photo provided.

The Tea Horse Road is a trade route

but also a path of cultural exchange and civilizational integration.

The Tea Horse Road is a cross-regional, cross-ethnic

network of folk trade and transportation.

Within China, it connects Han, Tibetan, Qiang, Yi, Mongolian, and other ethnic groups.

The commodities traded along the ancient route enrich the shared items, technologies, languages, cultures, and more among these groups,

deepening the foundation of mutual recognition.

Heshun Caravans. Source: Yunnan Provincial Department of Culture and Tourism

The differences in natural environments along the Tea Horse Road

resulted in complementary products.

Caravans traded textiles, tools (like Qiongzhu canes, ironware, glass), currency (like seashells, copper coins), food (like salt, tea), and other goods along the ancient route,

fostering interactions among the various ethnic groups.

The trade activities brought abundant supplies

and spread production technologies.

According to the Tang Dynasty's “Book of the Southern Barbarians,”