The I Ching: The Book of Changes says: “That which is above form is the Way; that which is below form is the utensil.” The utensil is the material carrier of the Way, while the Way is the spiritual attribute of the utensil. The interaction between these two has formed a variety of cultural phenomena. Tea culture is no exception. Through the material activities of picking, processing, transporting, storing, and drinking Tea, along with the spiritual culture inherent in these practices, it has gone through a process of emergence, development, and evolution. This has left us with various physical artifacts and a rich body of classical literature.

Tea utensils have evolved alongside the development of tea culture. A significant portion of the archaeological remains and extant artifacts related to tea culture are tea utensils. There are also many historical records and documents about tea utensils in the literature on tea.

When we mention tea literature, we generally refer to various tea books (the most comprehensive collection being Comprehensive Edition of Tea Books Throughout Chinese History with Annotations, containing 114 works, some of which are actually tea essays rather than full books). There have also been compilations of tea essays and tea poetry from all types of classics (the most extensive being The Chinese Tea Canon, published by Guizhou People's Publishing House in 1995). These provide basic resources for our compilation of tea utensil literature.

Tea utensils were created out of the need for people to pick, process, transport, store, and drink tea. As society developed, they became a combination of high art and everyday items, occupying an important place in the material and spiritual history of the Chinese nation. They are closely linked to culture and are also commonly used items in daily life, embodying both the character of the Way and the utensil. Tea utensils have evolved in response to changing human needs, each period producing distinctive styles. By examining tea utensils, we can understand the characteristics of tea culture during different periods and gain insight into the culture, thought, customs, and habits of the time. Historical tea utensils vary in shape and type, and we can learn about their history from relevant literary records, as well as from extant collections and archaeological discoveries. Of course, as a culture primarily embodied in material form, tea utensils also contain rich ideological and artistic content. Tea utensils from each era can give us a glimpse into the social culture of that time.

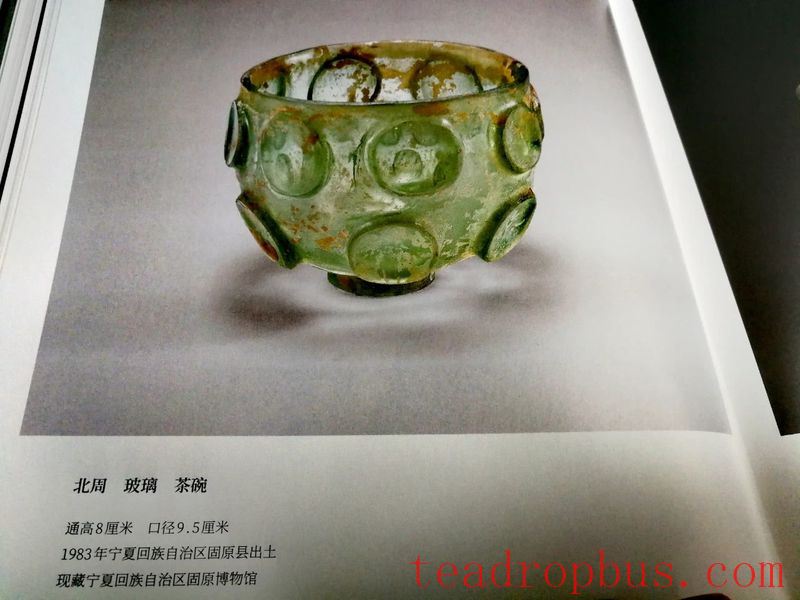

As early as the Western Zhou period (approximately 11th century BCE–771 BCE), tea was used medicinally, as a sacrificial offering, and began to be consumed as a beverage. However, at that time, food and tea were not separated, and utensils were often used for multiple purposes, including tea, alcohol, and food, without specialized tea utensils. By the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), the custom of drinking tea had become widespread, and tea had started to become a commodity. The earliest written record of Tea drinking appears in Wang Bao's Tongyue from the third year of Emperor Xuan's reign (59 BCE), mentioning “preparing tea and all its utensils” and “buying tea in Wuyang,” indicating that “tea” had become one of the dietary items of the time and that the custom of drinking tea had begun to spread among the upper classes of society. However, tea utensils had still not separated from eating utensils at this time. During the Wei, Jin, and Southern and Northern Dynasties, tea utensils continued to use cooking, boiling, and drinking utensils. With the promotion of tea drinking and the deepening understanding of tea, by the Six Dynasties period, specialized tea utensils had emerged from dining utensils and wine vessels, and the number of types had greatly increased. However, there were still relatively few records about tea utensils in the literature of the time.

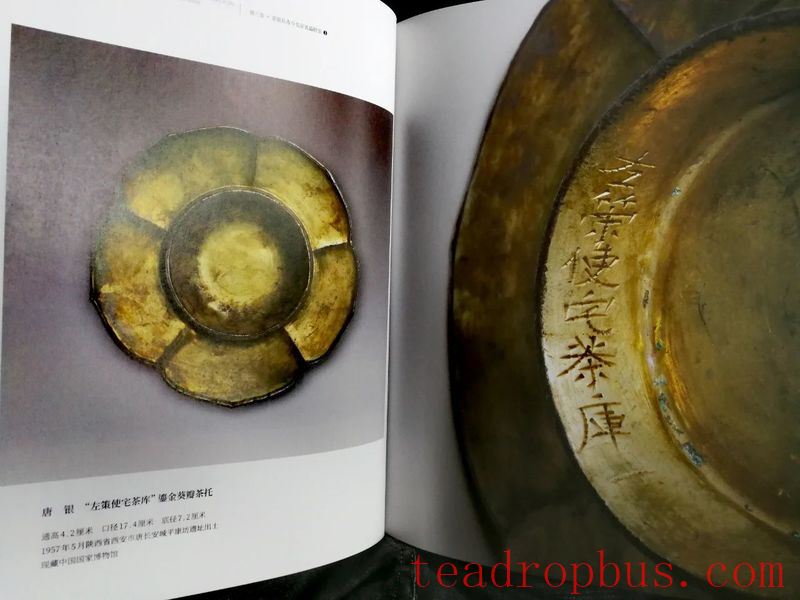

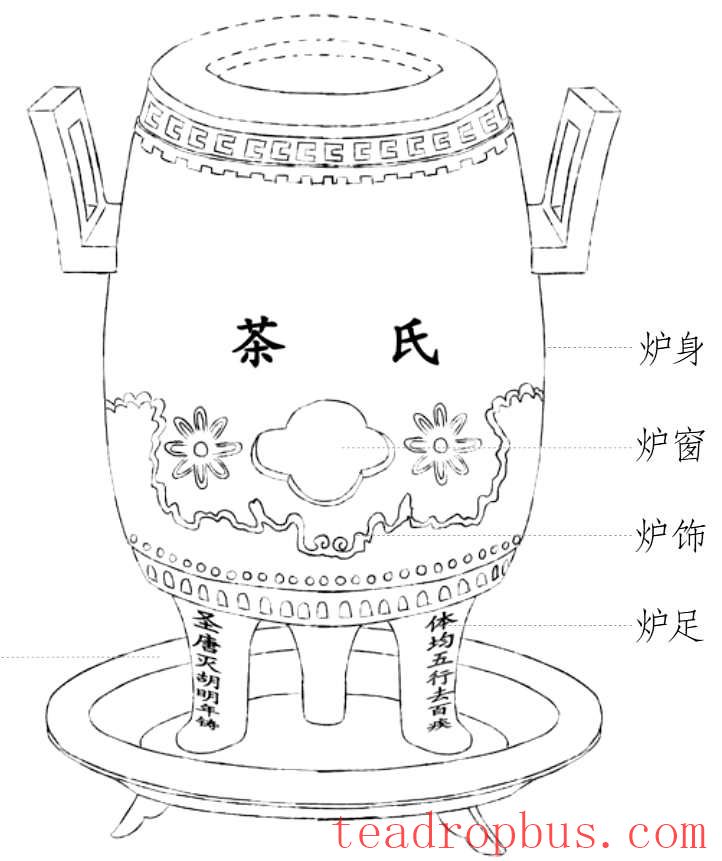

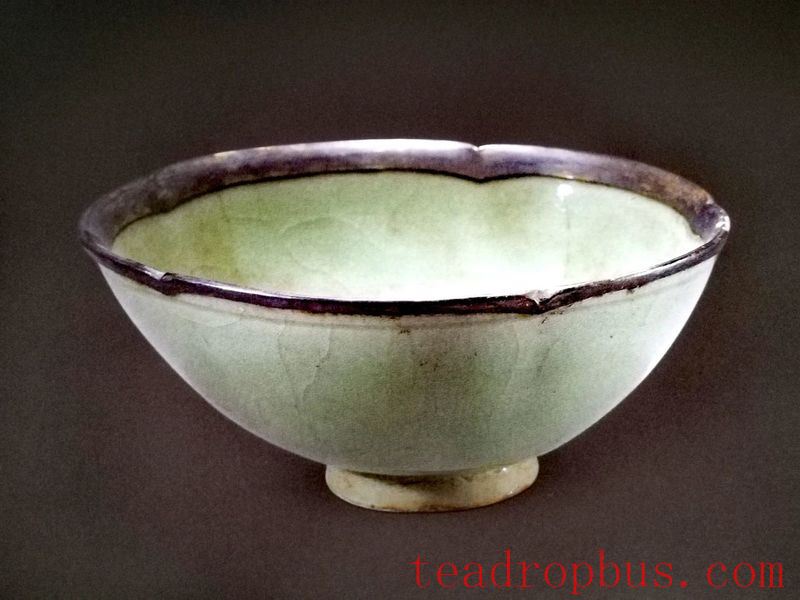

During the Sui and Tang dynasties, there were even more varieties of tea utensils, which were more complete than before. According to Lu Yu's The Classic of Tea, there were 28 types. Ceramic tea utensils predominated, but noble families and wealthy households also used metal tea utensils made of gold, silver, copper, and tin. Due to different local customs, the tea utensils used in Tang society were much more complex than those recorded in The Classic of Tea. This can be seen from relevant artifacts unearthed at places like Famen Temple and records in Tang poetry. According to The Classic of Tea, the method of tea drinking at this time emphasized the selection of tea, utensils, and water, as well as the skills required for brewing. It had evolved from simply quenching thirst to a higher level of tea appreciation culture. Scholars would even use the beauty of the utensils to enhance the quality of the tea, and celadon tea bowls from Yue kilns, which were “like jade” and “as clear as ice,” complemented the tea beautifully and thus became popular. With the transition from boiling tea to pouring tea, new utensils appeared, such as the side-handle pot and tea tray. This change became an important subject for Tang scholars' poetry.

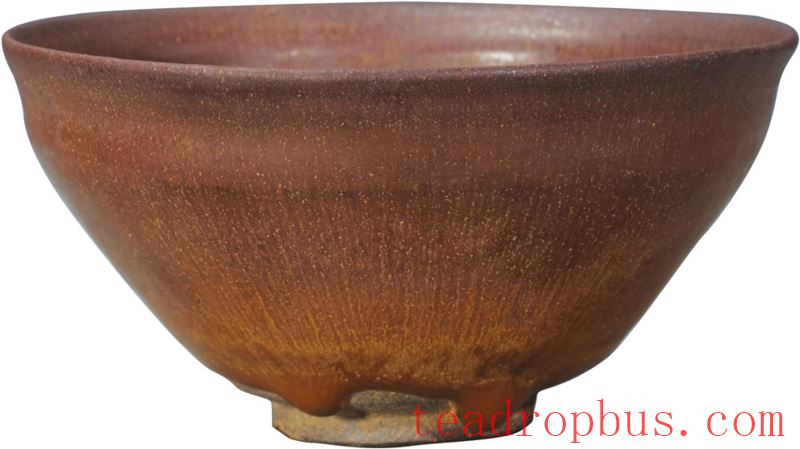

In the Song Dynasty, changes in tea production and methods of consumption, combined with the fashion of tea competitions and tea appreciation, led to several significant changes in tea utensils. Firstly, compared to the Tang Dynasty, Song Dynasty tea utensils were more refined and smaller in size. Secondly, due to the need for tea competitions, black-glazed tea bowls occupied an important position in the daily tea consumption of the Song people. Thirdly, many treatises on tea utensils appeared during the Song Dynasty, with Cai Xiang's Tea Record, Emperor Huizong's Comprehensive Treatise on Tea, and the anonymous Praise of Tea Utensils from the Southern Song Dynasty being the most famous.

There are fewer records about tea utensils from the Yuan Dynasty, but we can find some information about tea drinking and tea utensils during the Yuan Dynasty through scattered records in poems, paintings, and archaeological discoveries. Both the point-brewing method and direct brewing with boiling water were used during the Yuan Dynasty, as evidenced by Yuan poets' works and archaeological finds. The transitional nature of tea drinking methods directly influenced Yuan Dynasty tea utensils.

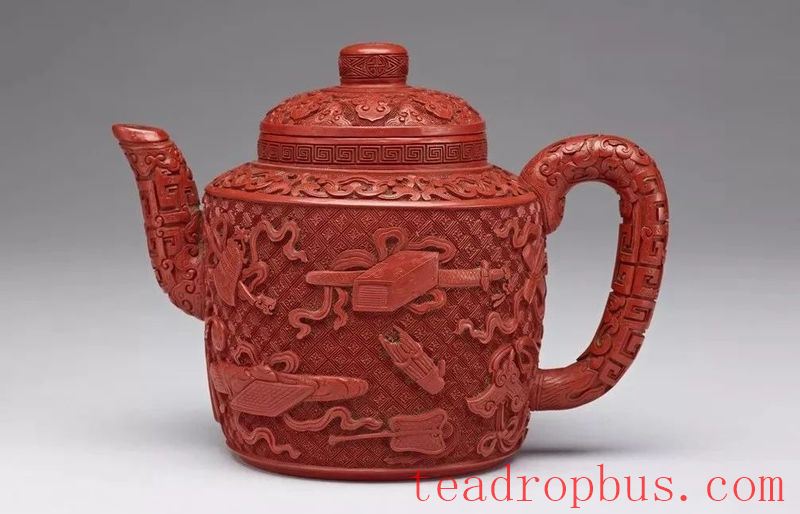

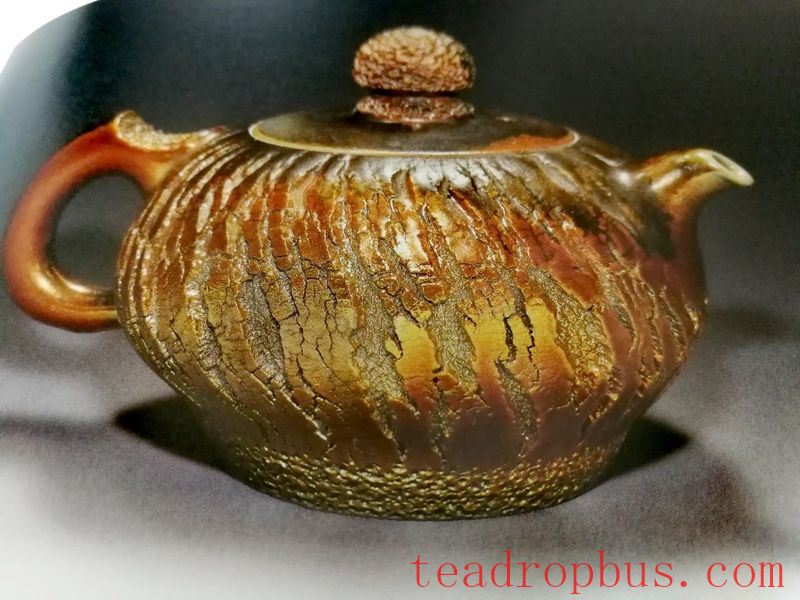

During the Ming Dynasty, there were some significant improvements in tea utensils, such as the ban on the production of dragon tea cakes in the twenty-fourth year of Hongwu (1391), which promoted the improvement and popularity of loose tea. Due to the emperor's advocacy, the Ming method of drinking tea involved steeping, which has been followed to this day. With the change in tea drinking methods, people's attitudes towards tea and aesthetic preferences also changed significantly. Tea competitions had largely disappeared, so black-glazed bowls were no longer suitable for the times, and white-glazed bowls became popular again. White porcelain tea utensils from Jingdezhen, Jiangxi, were widely welcomed and gradually developed into the center of porcelain production in the country. In general, Ming Dynasty tea utensils were relatively simple, but Gao Lian's Zunsheng Babian lists 16 pieces, plus seven additional storage utensils, totaling 23 pieces. Some scholars believe that this was a way for Ming scholars to express their desire for purity and inspiration when their real-world aspirations could not be realized. Teapots and teacups were the most important utensils in the steeping method, leading to the rise of purple clay teapot art, which developed into a highly artistic pottery industry. Another innovation in the Ming Dynasty was the addition of lids to cups, making the three-in-one cup (cup, saucer, lid) the standard format for Ming tea utensils. During the Qing Dynasty, with the increase in tea varieties, the methods of