To appreciate a Purple Clay Teapot, one must first have a standard. For Chinese calligraphy, painting, and even chess and music, there have long been standards for evaluation. However, for the purple clay Teapot, such standards have not yet been established. Recently, although there has been much discussion, some only touch on one aspect while neglecting the essentials; others may understand the truth but fail to express it eloquently. Readers often consider this a regrettable matter. I, being no genius, have collected insights from ancient and modern times, learning from many masters, and hereby establish these “Six Essentials for Appraising Teapots” as a standard. What are the “Six Essentials”?

- 1. Spirit and Grace

- 2. Form

- 3. Color

- 4. Interest and Taste

- 5. Literary Mindset

- 6. Utility

Spirit and Grace

The first of the “Six Essentials” and the most important is spirit and grace.

All teapots have form, but not all possess spirit and grace. “Spirit” refers to vitality and dynamism, while “grace” pertains to poise and elegance. These qualities can be sensed but not explicitly described. Teapots with spirit and grace have distinct personalities and a sense of life. Those without spirit and grace are lifeless; mere utensils made of clay, not worthy of being considered art. Sometimes, the difference lies in the subtle variations of rhythm and harmony, despite similarities in size, height, curvature, and angles. This distinction immediately reveals the elegance or vulgarity of the pot, and the maker's cultivation, thoughtfulness, and creativity become evident.

Therefore, it is easy for makers to imitate the form of a teapot, but difficult to capture its spirit and grace. The spirit and grace displayed by a teapot, such as simplicity, delicacy, clarity, toughness, freshness, innocence, elegance, grandeur, simplicity, brightness, elevation, purity, lightness, softness, and firmness, are all refined and full of vitality. In the past, Su Dongpo wrote: “Fine Tea is like a beautiful woman.” The same can be said for fine teapots; some are dignified like beauties from Yan and Zhao, while others are graceful like charming women from Wu and Chu. Although their styles differ, they each possess their own beauty.

A teapot with spirit and grace brings vitality to a home. On the other hand, a room filled with vulgar teapots might as well be filled with discarded mud.

Form

The spirit and grace of a teapot cannot exist independently but must be revealed through its form. This is known as “sensing categories through form.” The spirit resides within the form and communicates through the object, allowing people to naturally sense it. Therefore, without form, one cannot see the spirit. A teapot may have form but lack spirit, but without form, there is nothing for the spirit to attach to. One must seek the spirit within the form and the grace within the state. Form consists of points, lines, surfaces, size, height, thickness, thinness, squareness, roundness, curves, and angles. Even the slightest deviation can lead to significant errors.

Form and state are different. There are three forms: ribbed pattern, geometric, and natural.

The “ribbed pattern” form resembles the veins in a leaf. On the surface of the pot, there are similar fold lines with raised ridges. The areas between the ribs are rounded and raised, not externally attached. Some petal-shaped teapots are similar to ribbed patterns and should be considered a combination of ribbed and natural forms.

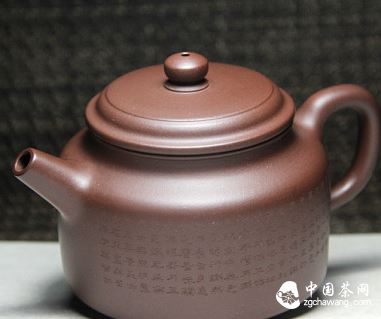

The “geometric form” uses geometric shapes for design, such as squares, rectangles, diamonds, spheres, ellipses, cylinders, or other geometric shapes.

The “natural form” is entirely based on the shapes of natural objects such as plum branches, pumpkins, pears, flowers, fruits, trees, and animals. However, there are also teapots that only slightly resemble something found in nature, such as a chrysanthemum bud teapot, which looks somewhat like a chrysanthemum bud but not entirely. These can be called quasi-natural forms.

State also includes three states: static, dynamic, and balanced. These three states embody three types of beauty: stillness, movement, and simplicity. Of course, some combine stillness and movement.

Within the form, there is a sense of softness, firmness, and a combination of both. There is also the concept of squareness within roundness, roundness within squareness, and the interplay of the two. Some teapots stand erect and stable, others are upright and firm, and others exude vigor. From this perspective, half of “state” belongs to spirit and grace, but there is a slight difference. Just like a beautiful woman, her charm comes from her posture.

Form is the body of spirit and grace.

In addition to the “three forms” and “three states,” there are also “three levels,” referring to the highest point of the handle and spout being level with the mouth of the pot. “Three levels” is a general principle for teapots, though not an absolute one. Achieving “three levels” easily conveys a sense of balance, but it is also possible to achieve a unique beauty by breaking this rule. Breaking the “three levels” should still be based on the principle of “three levels.”

Besides the “solid form,” there is also the “void form,” such as the space formed between the handle and the body of the pot, the space between the handle and the lid, or the space occupied by a curved spout. These spaces are referred to as “white space,” similar to the concept of “treating white as black” in painting, known in Pottery as “treating void as solid.” This “space” has its own shape and is part of the teapot, significantly influencing its aesthetic appeal and refinement. When designing the handle, whether square, round, oval, or angular, in addition to considering its solid form, one must also consider how to create a beautiful and appropriate void form (space) that harmonizes with the spout and body. The void form is just as important as the solid form and should not be taken lightly by either the maker or the appraiser.

Color

The color of a teapot must also be carefully considered. The clays mined from various mountains around Yixing come in colors such as purple, yellow, vermilion, black, white, green, and brown; if mixed and processed, even more colors can be achieved. Each color has variations in depth, brightness, and darkness. They can be used individually or in combination, with the aim of creating a color that is neither too bright nor too vulgar, but rather solemn, elegant, simple, natural, fresh, cold, bright, and gentle, so that viewers find it pleasing to the eye and soothing to the heart. If the color is overly bright, dull, gaudy, or flashy, viewers will feel uneasy at first sight, or find it jarring, irritating, or uncomfortable, and such colors are not suitable for refined