The other day, we introduced the Five Great Kilns of the Song Dynasty, and a Tea enthusiast asked: Why isn't the Jian Kiln included?

In fact, the Song people had a particular fondness for Jian tea bowls, and using them in tea competitions was a significant trend during that era. However, the Five Great Kilns were designated later, and since the method of brewing tea changed over time, the Jian Kiln was not included among them.

Jian tea bowls became highly prized treasures pursued with great expense by the royal and aristocratic classes of the Song Dynasty, as well as subjects of poetry and literary admiration.

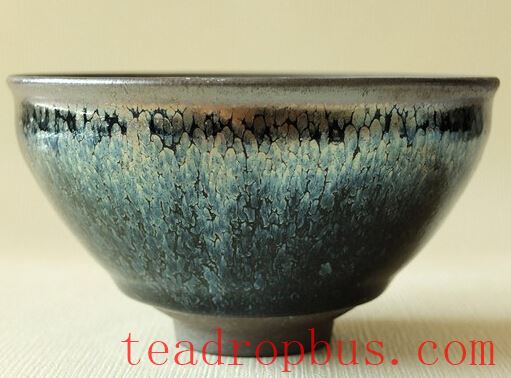

Besides the well-known facts that “White Tea looks best against a black bowl,” “the thicker the body, the longer it retains heat,” and the unique “hare's fur” and “partridge speckle” glazes, what are the unique characteristics of Jian tea bowls that made them so favored by tea competitors in the Song Dynasty?

Fragment of a Black Glazed Jian Bowl

There are numerous records from the Song Dynasty about Tea drinking. There are also many references in poetry and lyrics.

Tao Gu recorded in his “Qing Yi Lu” (Records of Peculiar Things): “In Fujian, tea bowls are made with patterns resembling the speckles of a partridge, which are treasured by tea connoisseurs.” This refers to Fujian, where Jianyang is located, and its production of tea bowls.

What are “partridge speckles”? They are the markings found on the feathers of a partridge, a bird with many spots on its plumage. Tea bowls imitate these biomorphic features.

Chinese Partridge

Oil Drop (Partridge Speckle) Bowl

Biomorphic tea bowls are very common in Jian ware, such as hare's fur bowls, which resemble rabbit hair.

In “Da Guan Tea Treatise,” Emperor Huizong of Song wrote: “Tea bowls should be valued for their dark blue-black color, and those with clear hare's fur streaks are considered superior.”

This means that dark blue-black bowls are the best, and those with streaks known as “hare's fur” are considered top quality.

Wild Gray Rabbit

Hare's Fur Bowl

“Jian bowl” is our term, but there was another term used in the past that we no longer use, which the Japanese still use: “Yao Bian.”

A superstitious account from Ming dynasty notes stated that when Jian bowls were fired, the blood of a virgin boy and girl must be offered as a sacrifice. The essence would then coalesce on the surface, hence the term “Yao Bian.”

The term “Yao Bian” is not commonly used in China today, but it is used in Japan. If you look up Japanese ceramics books, you will certainly find the term “Yao Bian.”

Many people think that this term originated in Japan, but it did not; it is actually Chinese and was later transmitted to Japan, where it remained in use. The Japanese refer to it as “Yao Bian.”

(One theory suggests that the Japanese term “Yao Bian” originally comes from the Chinese term “yao bian,” meaning “kiln transformation.”)

Japanese National Treasure Yao Bian Tenmoku

There is another interesting term: “Tenmoku.” How did “Tenmoku” come about?

There are countless explanations, but one that is closest to historical fact and most convincing is that Japanese monks brought back tea utensils from Mount Tianmu in Zhejiang province when they visited China. This explanation is more credible and easier to accept.

When Japanese monks brought Chinese Tea-drinking methods and utensils back to Japan, it was natural to call them “Tenmoku.”

Nowadays, any black porcelain from the Song Dynasty is referred to as “Tenmoku ware.”

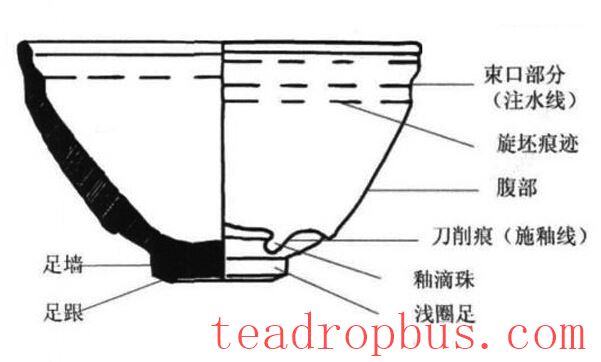

Shape of a Tied Mouth Bowl

(The tied mouth bowl is the most typical and common shape of Jian bowls.)

During the firing process of ordinary black glazed Tenmoku, changes in temperature led to unexpected beautiful variations like oil drops and hare's fur.

However, the formation of Yao Bian is even more complex – it requires extremely special firing conditions. According to scholars' research, in the dragon kilns built along the mountainside in Jianyang, pine wood was used, which produced high flames, allowing the kiln to heat up quickly and maintain a reducing atmosphere easily. Skilled kiln workers could control the position and temperature to produce some transformed objects.

At first, it may have been coincidental, but later, they likely tried to intentionally produce them, albeit at a ratio of approximately one out of every 100,000 bowls.