In ancient times, “Tea utensils” and “Teaware” were two terms with completely different meanings and classifications. However, as the method of tea drinking evolved over time, the definitions and functions of these terms merged. Thus, the scope of what we now refer to as teaware (or tea utensils) has actually narrowed, primarily referring to implements used for drinking tea. With modern advancements in living standards and culture, teaware production has entered a prosperous phase characterized by high volume, diverse types, and an abundance of creative designs. This has attracted an increasing number of collectors to the teaware field, gradually integrating teaware collecting into their daily lives.

The reason teaware is so closely tied to everyday life can be attributed to two important factors. First, the threshold for collecting teaware is relatively low compared to traditional collectibles. The price range for teaware is broad, from pieces costing tens of thousands of yuan to those that cost just a dozen yuan. Interested collectors can start their collections with items priced in the hundreds or thousands of yuan, making it accessible as an entry point into teaware collecting. Second, teaware has high practical value. Generally speaking, antique items kept at home are usually stored away and not used, serving only as decorative items that maintain their value. Teaware, on the other hand, is different because its functional use reduces the risk of purchase for collectors. Even if one is deceived, being able to use the item can mitigate losses to some extent.

In addition, the significance of teaware collecting, based on its proximity to daily life, is also a means of enhancing the quality of life.

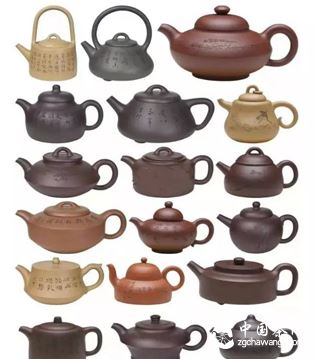

The aesthetic value inherent in teaware is the first aspect to consider. We gain aesthetic appreciation from teaware through its craftsmanship, starting with evaluating the manual workmanship. Generally, whether the transition between points, lines, and surfaces in the teaware's shape is natural and smooth is crucial in highlighting its overall character. Taking the example of a purple clay Teapot, the spout, mouth, shoulder, belly, base, spout, and handle are the basic areas for appraisal. When examining details, one can inspect the seat of the knob, lid surface, spout opening, spout base, transition, handle base, and inner circle of the handle.

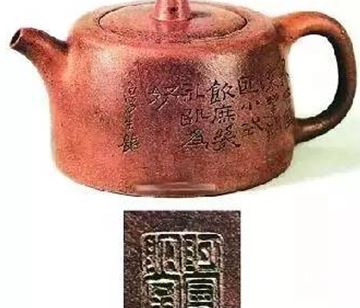

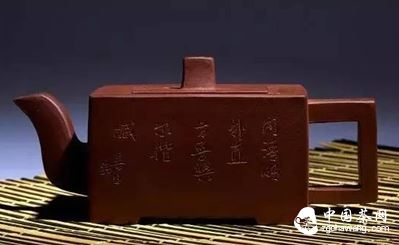

Besides observing the “shape,” the engraving and calligraphy on the surface of teaware can greatly enhance its aesthetic appeal. Delicate engravings and calligraphic paintings are fundamental elements that skilled artisans impart to teaware. If the teaware is crafted by a famous artist, imbued with the creator's personal philosophy and spirit, it becomes culturally meaningful. For instance, inscriptions on the surface of a purple clay teapot or landscape paintings on porcelain tea sets provide people with a sense of beauty in their daily lives.

Secondly, teaware collecting plays a role in cultivating one's mind and body in daily life. Through playing with teaware, nurturing it, and enjoying the sensory experience during tea drinking, one can alleviate the pressures of life, achieving a calming effect.

When scholars became involved in tea-drinking rituals, teaware emerged with a small, exquisite, and elegant form, becoming a favored item for play. The “Jiaocha Jian” describes how Ming Dynasty scholars played with Teapots: “Teapots, with kiln-fired ones being superior, are prized for their small size, with each guest having their own pot to pour from, fully capturing the essence of the experience.” Purple clay teapots were discovered by tea enthusiasts in the mid-Ming Dynasty. Their texture lies between pottery and porcelain, warm and simple, fitting the temperament of scholars, who enjoyed handling them daily, warming them with their body heat to achieve a smooth, lustrous appearance.

Chen Mansheng

In earlier times, Chen Mansheng designed his own teapot shapes and invited the master craftsman Yang Pengnian to make teapots according to his designs. Yang Pengnian's teapots received praise from Chen Mansheng, with the seemingly casual wrinkles on the delicate teapots providing great pleasure for Chen as he played with them.

Mansheng Eighteen Styles

Nowadays, people continue this tradition of playing with teaware and commonly use teapot nurturing as a leisure activity. Collected purple clay teapots can be nourished daily with tea, developing a luster over time that appears like purple jade on the outside and like green clouds within, emitting a subtle, radiant glow. Over time, a bond forms between the tea enthusiast and the teapot, a connection that is difficult to express in words.

Experiencing the texture of teaware with one's hands is a form of enjoyment. Additionally, the five senses can appreciate Tea culture through the use of teaware during daily tea drinking.

As the saying goes, Yixing clay teapots are considered the best, while white and pure-white cups are ideal. White porcelain is most suitable for observing the color of tea, providing a visual delight. The sound of water pouring into a teapot is pleasing to the ear. The aroma of brewed tea in a purple clay teapot, smelled before sipping, is a treat for the nose. Tasting the tea after smelling its fragrance is a delight for the palate. The utilization of teaware in tea drinking provides a more direct sensory experience for the five senses. These experiences can help clear the mind, soothe the spirit, and lead to insights, allowing the tea enthusiast to relax mentally.

Thus, the eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, and mind have concrete experiences with the help of teaware collecting. Moreover, the philosophical implications contained within this process are revealed, offering interpretations and sudden enlightenment related to Buddhist principles.

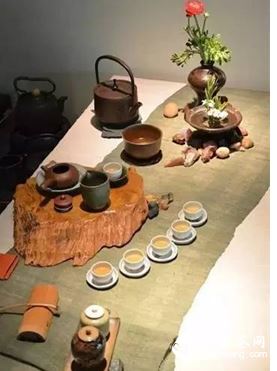

Lastly, teaware collecting serves as an element in interior design, adding classical elegance to living spaces.

Teaware played a vital role in the lives of literati during the Song and Ming Dynasties. The four arts of the Song people—burning incense, brewing tea, hanging paintings, and arranging flowers—were continued in the Ming Dynasty. Ming literati regarded tea tasting as a high art of living. They expressed their reverence and enthusiasm for tea ceremonies by standardizing the use of tea utensils, the number of participants, the environment, and the atmosphere. In terms of space construction, they tended towards a romantic style shaped by personal whimsy. It was precisely due to this that independent tea rooms became possible later on.

Today, this lifestyle of literati tea rooms is being