During the Song and Yuan dynasties, tea production shifted from traditional compressed teas to powdered and loose leaf teas. At the same time, “tea dueling” became a new national trend in Tea drinking.

During the Song and Yuan dynasties, tea production shifted from traditional compressed teas to powdered and loose leaf teas. Simultaneously, “tea dueling” became a new national trend in tea drinking. In Fujian Province, with the development of Quanzhou Harbor and unprecedented growth in overseas trade, the opening of the maritime “Silk-Ceramic” route, and the southern shift of the economic center of the Song people, the tea industry in Fujian flourished even more. Tea from Fujian had already been listed as a tribute item during the Tang Dynasty, and by this point, it had become renowned throughout the country. In Fujian, at least five prefectures produced tea, and books stated that “Fujian's tea is particularly favored across the world” – Fujianese tea became the beloved choice of all. The region around Jianzhou in the northern gardens was a famous source of tribute teas and imperial kilns. Zhou Jiang's Comprehensive Record of Tea Gardens states: “Of all the teas in the world, those from Jian are the best, and among those from Jian, those from the Northern Gardens are the best.” Emperor Da Guan praised them, saying: “Since the rise of our dynasty, every year we pay tribute with the teas of Xijian, where dragon-sphere and phoenix-cake teas are renowned across the world” (The Da Guan Tea Treatise). The rise of Jian teas greatly stimulated the prosperity of the ceramics industry in Fujian. Kiln smoke could be seen everywhere along the slopes of Mount Wuyi and the banks of the Min River, and the crisp sounds of porcelain were heard constantly.

During this period, in addition to inheriting some types of tea ware from the Tang dynasty, such as large-scale production of green porcelain bowls, water pots, and tea cups (with saucers), some types of tea ware underwent significant changes. For example, the saucer for tea cups almost became a fixed accessory, and there were more styles available. In 1978, two styles of green porcelain saucers were unearthed from a Song tomb on Jiulong Mountain in Shunchang: one style had a relatively high saucer, with variations in wide flared rims and straight mouths; the other style had the cup and saucer fixed together. In areas south of the Yangtze River, apart from ceramic and Silver saucers, there were also golden saucers and lacquered saucers.

In the Song dynasty, tea was mostly drunk from cups. Those cups with flared mouths and small feet were shaped like straw hats and were also called “straw hat bowls.” According to archaeological evidence, Song dynasty tea cups were divided into four types: black glaze, brown glaze, green glaze, and bluish-green glaze. Among these, “black glaze” cups were the most popular.

The poem says “the fame of Jian kiln resounds across the world.” When discussing the quality of black glaze, one must mention the Jian kiln. Equally well-known alongside the North Garden teas of the Song dynasty were the black-glazed tea wares produced by the Shuigai kiln in Jianyang. These black-glazed tea cups, as tribute items “for imperial use,” also became treasured possessions across the world.

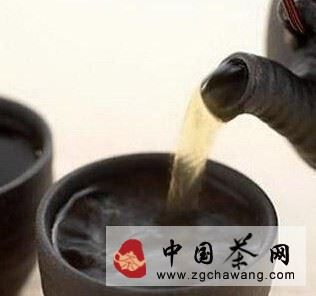

Indeed, the reason why the Song people were so fond of black-glazed tea wares produced by the Jian kiln was deeply rooted in their tradition of tea dueling. In Song dynasty tea dueling, finely ground tea powder was placed in tea cups, and while boiling water was poured over it, the mixture was stirred with a tea whisk until it formed a suspension and froth accumulated around the rim of the cup. The winner was determined by who had tea that “stuck to the cup without leaving any water marks.” Cai Xiang introduced Jian'an tea dueling in his Tea Record, placing particular emphasis on a semi-fermented White Tea produced locally. This was because “in tea dueling, color is the first criterion,” and white or bluish-white teas were prized, as they made the water appear heavier and darker, while green teas made the water appear clearer. In Jian'an, greenish-white tea was preferred over yellowish-white tea in tea duels. Due to the preference for white tea in tea duels, which provided a clear contrast against the black background, black porcelain tea cups were essential: “White tea looks best in black cups, as any marks are easily visible” (Zhu Mu, Geographical Records of Famous Places, Song dynasty); the Da Guan Tea Treatise also believed that “black cups are the best, with those displaying jade-like streaks being superior.” These “jade-like streaks” referred to variegated cups. A good cup with vibrant colors and smooth lines could make the tea color shine, with the scenery emerging according to the surroundings. The cup acted as the backdrop for the tea, and the bright and luminous tea scene benefited from its supporting and creating role. During the Ming dynasty, however, Xie Zhaozhi found Cai Xiang's use of black cups difficult to understand, thinking “the color of tea should naturally be greenish, how could it be pure white?” –– this change in the type of tea influenced the selection of tea ware. In the Song dynasty, the focus was on ground tea, looking at the foam, and observing “the patterns of partridge spots on the surface of the tea cup, like clouds swirling in words, and the whiteness of rabbit fur in the center of the cup, like a pool of snow” (Sibu Congkan shadow Song dynasty manuscript, Chengzhai Ji, Volume 19). However, during the Ming dynasty, with the focus on young tea leaves, the tea infusion was green after brewing, and therefore, black cups were no longer used, and instead, “white and sturdy” cups (from Wu Za Zu) were the preferred choice. Only the Yuan dynasty separated the Ming and Song dynasties, yet Xie was completely unaware of the previous tea-drinking customs, which seems a bit strange. These are stories for another time.

The bottom of tea dueling cups needed to be slightly deeper and wider – a deeper bottom helped the tea stand up, making it easier to produce foam, while a wider bottom allowed the tea whisk to stir vigorously without hindrance. The tea cups from Shuigai's Jian kiln not only had these advantages but also the benefit of thick walls that helped retain heat. Thick walls prevented the tea from cooling quickly, allowing the water marks inside the cup to last longer. As Cai Xiang wrote in his Tea Record: “White tea looks best in black cups. The ones made in Jian'an are deep blue-black, with patterns resembling rabbit fur. Their walls are very thick, so they stay hot for a long time and do not cool down easily, making them the most useful. Cups from other places are either too thin or purple, and are not as good.” Considering the situation of porcelain kilns across the Song dynasty, about one-third of the kilns nationwide produced black-glazed wares at the time. In the north, the best black-glazed porcelain came from Cizhou and Ding kilns, while in the south, Fujian had the most kilns producing black-glazed porcelain, with nearly 20 counties and cities having kilns that produced black-glazed tea wares. The largest, highest quality, and most influential of these was the Shuigai kiln in Jianyang, covering an area of nearly 110,000 square meters.

The Jian kiln began operations at the end of the Five Dynasties and the beginning of the Song dynasty, mainly producing black-glazed tea wares (bowls, cups). It has the longest dragon kiln in China today (139.6 meters) and has unearthed tens of thousands of various daily utensils and tea wares, primarily black-glazed porcelain. Of