The successful nomination of Jingmai Mountain for World Heritage status has captured many people's attention, but it also raises questions: why Jingmai Mountain? After all, Yunnan is the richest place in the world for ancient Tea trees and ancient tea gardens, with a total existing area of ancient tea tree resources of approximately 329,680 acres. Of this, about 265,750 acres are home to wild-type ancient tea trees, while cultivated ancient tea trees (gardens) cover around 63,930 acres. Walking through the tea mountains of Yunnan, one is often awed by the vast ancient tea gardens nestled within dense forests, moved by the accumulation of time and the fruits of our ancestors' labor. In terms of scale, the ancient tea forest of Jingmai Mountain isn't the largest; its neighbor, the ancient tea mountain of He Kai in Menghai, is also “thousands of years old and tens of thousands of acres.” In terms of reputation, whether by price or name recognition, it can only be considered “second-tier” compared to Bingdao, Lao Banzhang, Yiwu, and others; in terms of the richness and diversity of indigenous cultures, the landscape is vibrant and varied, making it hard to pick a clear winner…

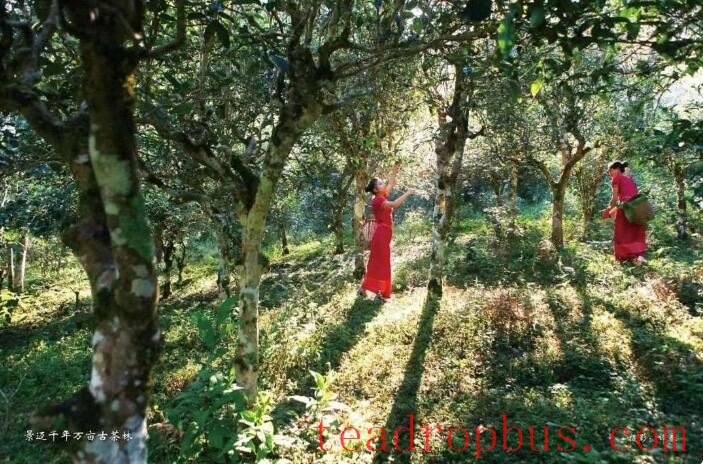

Ancient tea forest (Photographed by Tan Chun)

In a recently released video, Yunnan Tea culture researcher Zhou Chonglin “decodes” how Jingmai stood out during the World Heritage nomination process. The primary reason was local emphasis, with concerted efforts from the government, businesses, and the community. It cannot be overstated that decision-makers and participants at both the Pu'er City and Lancang County levels were both visionary and tenacious, demonstrating a precious “clear-headedness.” Of course, there were also efforts from higher up, particularly the professional and effective contributions from the field of cultural heritage preservation. Imagine, without over a decade of regulations and improvements along the World Heritage nomination journey, would Jingmai Mountain have the comfortable appearance it does today?

In fact, people's doubts reflect a misperception of the value of “World Cultural Heritage.” The “ancient tea forest cultural landscape” in “cultural heritage” is not about who has the largest area or sells the most expensive tea, nor even about who has the most legendary stories. Rather, it's about “authenticity and integrity.” Put another way, it's about who is more rustic, more professional, and more patient. For this reason, Jingmai Mountain can be seen as a representative and benchmark of the cultural heritage value of ancient tea mountains in Yunnan.

The cultural heritage elements of Jingmai Mountain include five ancient tea forests, nine traditional villages, and three buffer forests. These serve as physical evidence of “understory tea gardens” before the advent of modern terrace tea gardens. This model of mountain agriculture, settlement structure, and traditional tea garden techniques are similar across various ancient tea mountains in Yunnan, more like a “universal model.” It took me a long time to understand that because the support capacity of mountain agricultural resources is limited, the land cannot sustain too many people. Therefore, villages on the mountain must be dispersed for cultivation, and if a Village becomes too large, a new one must be established elsewhere. Otherwise, it's too far to travel to work on the mountain. Whether selected by golden deer or white elephants is another matter. There are boundaries between villages and between different tea plots, with the best “fences” being natural forests.

Walking through Wengji Village on Jingmai Mountain, an ancient Bulang village, the towering ancient trees encountered along the way are just as impressive as the traditional stilted architecture. Deputy Director Li Yang of the Heritage Department of the Pu'er Jingmai Mountain Ancient Tea Forest Protection Administration explained that if viewed from above, you would notice large trees surrounding the village. These large trees mark the village boundary and indicate the environmental carrying capacity. The more you learn about Jingmai Mountain, the more you appreciate the land ethics behind the cultural heritage and the rich details of harmony between heaven and humanity—ancient survival wisdom that is both harmonious and systematic, beautiful and scientific. This wisdom and these principles, passed down for centuries, were once considered backward or even shameful.

We should be grateful for the World Heritage nomination, which has given some seemingly “primitive” ways of life, cultural practices, and customs in Yunnan global recognition and promotion. It builds a bridge between academic theory and cultural dissemination, allowing us to reevaluate the value of tradition and making arrogant and utilitarian impulses seem trivial in comparison. At the foot of Jingmai Mountain, a world's first 10,000-ton intelligent tea cellar is under construction. Project leader Gan Changzhu told me that their high-end members shed tears when they come here for a stay and attend bonfire parties. Indeed, the flavors of the mountains and the guitars of ethnic minority singers have a captivating power, embodying “a way of life called Yunnan.”

Jingmai Village Nu Gang Ancient Village (Photographed by Shi Yueming)

The successful World Heritage nomination of Jingmai Mountain is the glory of all ancient tea mountains in Yunnan, as the logic of survival and natural terroir are highly similar across these mountains. This is not something to make other places envious or bitter but rather an opportunity to tell their own stories within the framework of “cultural heritage.” Jingmai Mountain becoming the first World Cultural Heritage site with a focus on tea is, at the very least, an honor for the Chinese Tea industry, celebrated by tea people worldwide. If one merely sees it as making the local tea more sellable or boosting tourism, then the perspective is too narrow. However, Jingmai Mountain's success also serves as a mirror for other ancient tea mountains in Yunnan: to reflect on what they have become and whether they are worthy of their ancestral heritage. As for the aspects in which Jingmai Mountain can serve as a mirror, I will elaborate further below.

Sunset at Mang Hong Village in Mangjing (Photographed by Su Kun)