The Tea Ship Ancient Route connects diverse civilizations across different regions, promotes cultural integration in areas it reaches, and nourishes the daily lives and spiritual homelands of countless people both at home and abroad.

The Tea Ship Ancient Route connects diverse civilizations across different regions, promotes cultural integration in areas it reaches, and nourishes the daily lives and spiritual homelands of countless people both at home and abroad.

Teahouse Culture Flourishes Widely

Every morning as dawn breaks, Wuzhou City gradually awakens. In the city, the time-honored Dadaong Grand Restaurant begins to welcome a busy day: waiters move nimbly between teahouse tables with large kettles, customers loudly request refills, Tieguanyin, Pu'er, Liubao… steaming pots of tea are served and then vanish down the throats of the tea drinkers. Following this, there are royal teatimes, afternoon teas, and night teas, one after another, until late into the night.

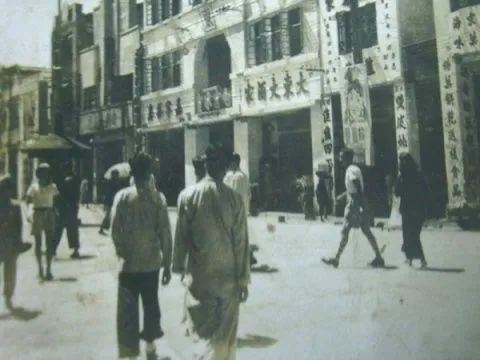

This picture shows the Dadaong Grand Restaurant in Wuzhou during the Republican era. Its predecessor was the Nanhua Hotel built in 1928, which had a full house of customers every day after opening.

This bustling scene is familiar to “old Wuzhou residents,” because for many years, teahouse culture has been prevalent in Wuzhou, and most Wuzhou people have developed the habit of going to teahouses to “savor tea.” According to “The Famous Dadaong Restaurant in Guangdong, Guangxi, Hong Kong, and Macau” written by Lu Xianqiang, a local author from Wuzhou, the predecessor of the Dadaong Grand Restaurant was the Nanhua Hotel built in 1928, which had “customers filling its doors every day after opening, and both officials and merchants considered Drinking Tea here an honor.”

As an important transit point on the Tea Ship Ancient Route, the development of teahouse culture in Wuzhou was already very evident in the early part of the last century. Scholar Zhao Yinting confirmed through research that in the late Qing Dynasty and early Republic period, there were two or three dozen tea and wine houses in the city center of Wuzhou. From 1921 to the first half of 1937, the number of tea and wine houses in Wuzhou reached over 60.

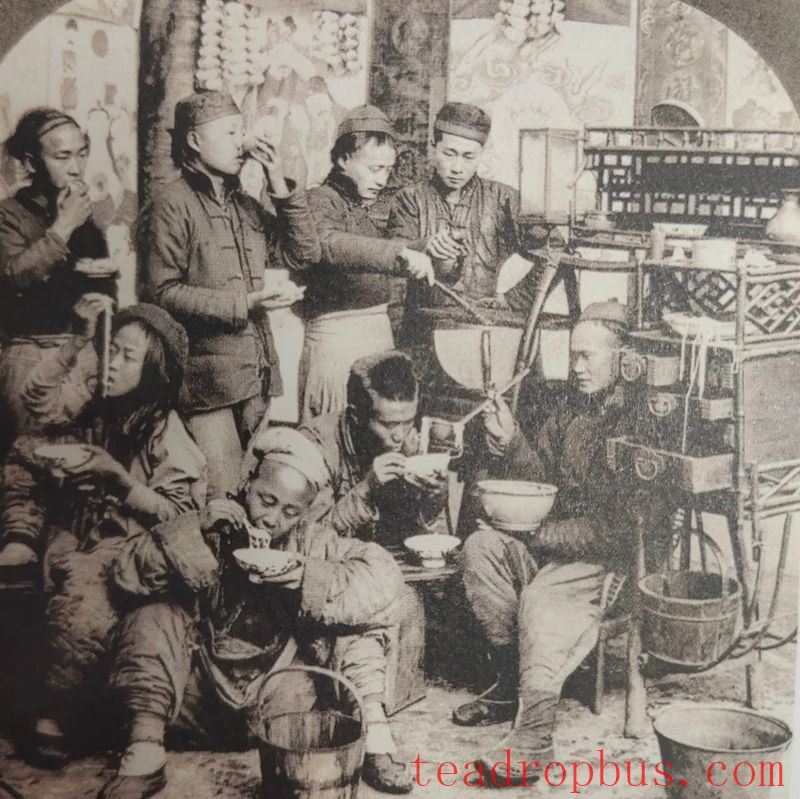

In the mid-to-late Qing Dynasty, roadside tea lodges in Guangdong were places for the working class to drink tea, eat, and rest.

Liu Fusheng, one of the founders of the Wuzhou Tea Factory, was attracted to Wuzhou's teahouse culture when he moved there in the early 1950s. “Back then, restaurants and flower boats were where Wuzhou's tea drinkers gathered most. I remember that hundreds of teahouse tables in the Dadaong Grand Restaurant were often fully occupied. People would sip tea, socialize, discuss matters, and conduct transactions, and the restaurant did brisk business.” To this day, Liu Fusheng still vividly remembers the bustling scenes in the teahouses and restaurants of Wuzhou in those days.

The thriving tea market wasn't unique to Wuzhou. Along the ancient route of Liubao tea exports, teahouse culture had permeated all levels of society and become an indispensable part of people's daily lives. In “Sketches of Rice Fragrance,” Jin Wuxiang recorded the situation of tea lodges in the early Guangxu period: “Outside the north gate of Guangzhou, there are many graves as far as the eye can see. At the end of the market area is Kuai Ge, a place for travelers to take a tea break… These simple roadside tea lodges were called ‘one-lian pavilions' (one lian being equal to 1/72 of a tael).” Soon, “two-lian pavilions” appeared in Guangzhou, which had fixed tables and chairs and offered not only tea but also pastries. Later, to meet the needs of the upper classes, more sophisticated tea houses and tea parlors emerged. Through their development, tea lodges and tea houses complemented each other's strengths and weaknesses, eventually merging into the modern Cantonese-style tea house.

The widespread teahouses and restaurants boosted tea consumption throughout the Xi River Basin. “Miscellaneous Records of the Qing Dynasty” records that from Wuzhou to Guangzhou, and even in Hong Kong and Macau, a huge consumer market absorbed tea from various sources, including “Guangxi green tea” like Liubao tea, which has been a staple in the teahouses of Guangdong and Guangxi since the mid-Qing Dynasty.

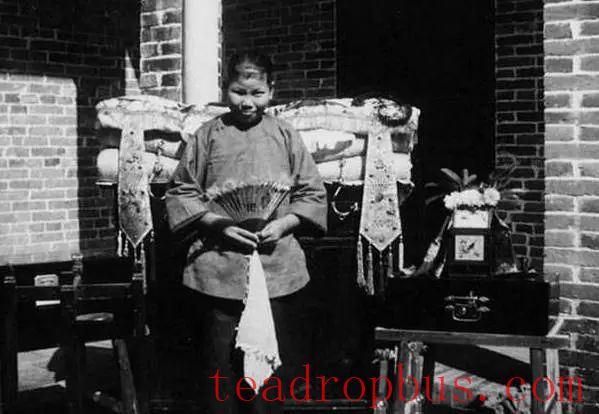

In 1936, a bride in the Wuzhou region poses with her dowry. At the time, tea was an essential part of a woman's dowry when she married.

The rapid development of the teahouse industry expanded the consumer market, and the growing tea industry further propelled the development of the teahouse industry. They complemented each other, mutually promoting each other's progress. This allowed Liubao tea to participate in the evolution of tea-drinking culture in Guangdong and Guangxi over the past century and played a significant role in its development. A closer look reveals that the flourishing of teahouse culture in Guangdong and Guangxi aligns closely with the formation and maturity of the Tea Ship Ancient Route. Both were shaped in the mid-to-late Qing Dynasty and entered a peak period of development.

Cai Yiming, deputy general manager of the China Tea Industry Co., Ltd. in Wuzhou, said, “The prosperity of the teahouse culture in the Pearl River Delta, Hong Kong, and Macau is intricately linked to the thriving production and sales of Liubao tea and the transportation support provided by the Tea Ship Ancient Route.”

Spiritual Bonds Connect Nanyang

Malaysian tea aficionado Huang Jinzhao has a special affection for Liubao tea. For over a decade, he has been involved in promoting and selling Liubao tea. A few years ago, he specifically visited Wuzhou to explore the cultural and historical roots of Liubao tea.

“My family especially loves drinking Liubao tea. I grew up with Liubao tea. When I was young, my grandfather would buy a large basket of Liubao tea at once, enough for the family to enjoy for half a year,” Huang Jinzhao said. “Malaysian Chinese have long loved Liubao tea. They believe it has unique medicinal benefits, so some Chinese medicine shops sell Liubao tea as a medicinal herb. Nowadays, Liubao tea has become a favorite for consumption and collection among Malaysian Chinese. There are over 50 tea shops in Kuala Lumpur, most of which sell Liubao tea.”

In 1949, advertisements for Yingji Tea Shop could be seen on the streets of Guangzhou. After 1950, the tea shop moved to Hong Kong.

As a waterway for tea transportation, the Tea Ship Ancient Route is uniquely significant in the history of Chinese Tea distribution. For the regions of Guangxi, Guangdong, Hong Kong, Macau, and Southeast Asia, the impact of this water trade route is even more profound. In the view of He Huaxiang, an associate professor of Chinese literature at Wuzhou University who specializes in intangible cultural heritage, the Tea Ship Ancient Route supports livelihood development, fosters urban prosperity, connects diverse civilizations across different regions, and nourishes the daily lives and spiritual homelands of countless people both at home and abroad.

“Under the influence of water culture and Tea culture, the Tea Ship Ancient Route serves as a peaceful bond, quietly creating wealth, sustaining