Tea enthusiasts often have their preferences when it comes to tea ware. Because they are used for brewing tea, these vessels are not only functional but also carry aesthetic significance. Here we present a selection of exquisite tea wares from various dynasties for your appreciation, inviting you to savor the lingering fragrance of tea that even time cannot take away.

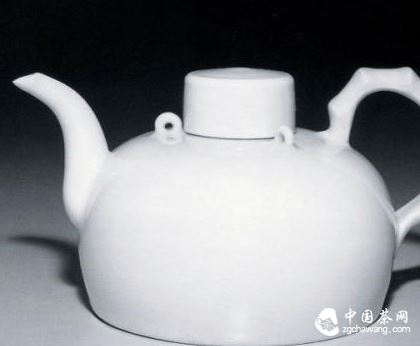

The sweet white porcelain Teapot from the Ming dynasty's Yongle period, part of the collection at the National Palace Museum in Taipei. It has a small round lip, a body shaped like half a circle, a bamboo node handle, and a flat-topped round lid. The entire piece is glazed in sweet white, with a glossy finish and a slightly thick body. During the Ming dynasty, after Emperor Hongwu ordered the discontinuation of the tribute of Compressed tea cakes, the method of grinding tea into a powder practiced during the Tang and Song dynasties gradually fell out of use. Instead, steeping loose tea leaves became the prevalent way of drinking tea, making the teapot the primary vessel for brewing.

The black-glazed Hare's Fur tea bowl from the Southern Song dynasty, housed in the Tokyo National Museum. It has a narrow mouth, a small base, and deep curved walls, with a silver rim around the lip. The entire surface is coated in black glaze, which is decorated with streaks resembling hare's fur, hence the term “Hare's Fur tea bowl.” Since the promotion of these bowls by scholars such as Cai Xiang, Mei Yaochen, and Su Dongpo in the mid-Northern Song period, they have been favored by tea duelists. The key to winning a tea duel lay in whether the white froth adhered to the sides of the bowl, covered the surface, and did not reveal the tea liquid beneath. To easily distinguish water marks and highlight the white froth, Black Tea bowls became an essential component in the preparation of tea for duels.

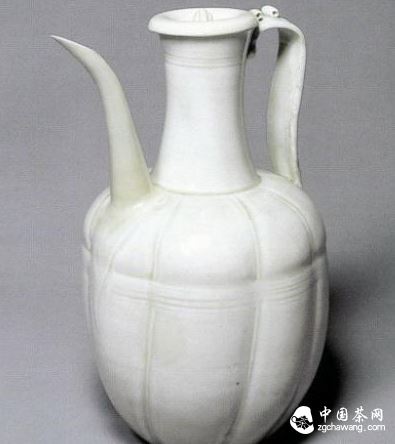

The celadon-green porcelain tea bottle from the Northern Song dynasty, part of the collection at the Tokyo National Museum. It has a slightly flared mouth, a long neck, broad shoulders, and a curved handle. It comes with a round lid, with corresponding holes on the lid rim and handle for a string to connect them. The spout is long and pointed, and the entire piece is glazed in celadon-green, exuding elegance and refinement. Known as a soup bottle, this vessel was used by the Song people to pour hot water directly into the tea bowl, making it indispensable for preparing tea. The spout of a tea bottle is typically long and sharply cut, a common feature of both gold and silver and ceramic tea bottles from the Song dynasty. As stated in Emperor Huizong's “Da Guan Tea Treatise,” “The critical factor for pouring hot water lies in the shape of the spout. A large and straight spout ensures a strong and focused pour without scattering. The end of the spout should be rounded and sharply cut, allowing the hot water to be poured in measured amounts without dripping. Hot water that pours forcefully and stops cleanly ensures that the tea surface remains intact.” To ensure a neat pour, a round, small, and sharp spout became a necessary condition for tea bottles in the Song dynasty, and one of its main characteristics.

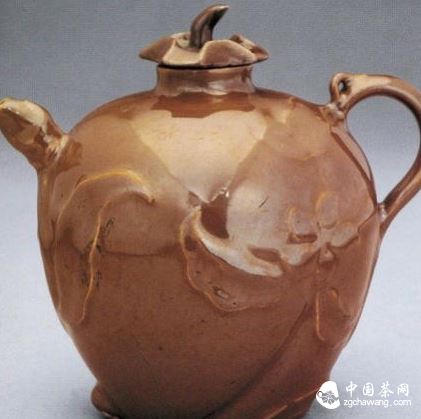

The green-glazed handle pot from the Tang dynasty, part of the collection at the National Palace Museum in Taipei. It has a round mouth, a short neck, sloping shoulders, and a full belly, with a rectangular hollow cross handle. The handle has a circular hole in the middle, allowing it to be connected to the round hole on the lid, which features a pearl knob. The entire piece is glazed in green, with a milky greenish hue. Cross-handle pots are commonly found in Hunan's Changsha kilns, and similar pieces have also been discovered in Zhejiang's Yue kilns. These pots were among the main products of the Changsha kilns, and in the late Tang dynasty, along with short-spouted tea bottles, they were used for pouring hot water to prepare tea.

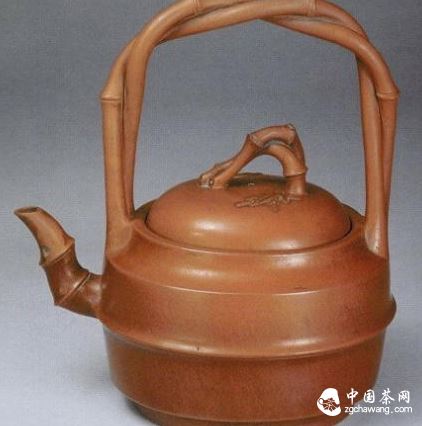

The Yixing purple clay bamboo-section handle pot made by Chen Yinqian from the Qianlong period, part of the collection at the National Palace Museum in Taipei. The teapot is shaped like bamboo sections, with an oval body adorned with a string of grooves. The spout is molded to resemble three bamboo sections, while the handle is formed by two slender bamboo branches twisted together. The bottom bears the seal mark “Made by Chen Yinqian” in seal script. Chen Yinqian was a famous Yixing potter during the middle of the Qianlong period, whose birth and death dates are unknown. He specialized in making bamboo-section handled pots, and several examples bearing his signature are known to exist, including those housed in the Nanjing Museum. This pot, having been used for a long time, bears traces of old tea stains, giving it a lustrous appearance and hinting at its popularity.

The celadon-glazed tea caddy from the Yongzheng period, part of the collection at the National Palace Museum in Taipei. It has a straight mouth, a short neck, broad shoulders, and a large belly, with the entire piece glazed in celadon, featuring an even and delicate hue and a fine texture. Celadon or blue-and-white tea caddies were particularly abundant during the Yongzheng period, indicating Emperor Yongzheng's fondness for tea. Although there are no extant poems or writings about his thoughts on tea tasting, the frequent mention of his gifting of tribute tea to officials, often including the tea jars and sometimes accompanied by tea bowls, suggests the popularity of tea drinking in the imperial court during the Yongzheng period.

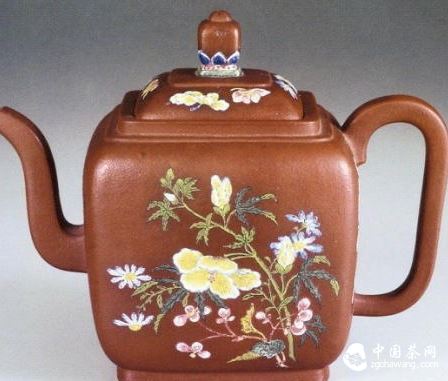

The square Yixing-bodied cloisonné enamel teapot with polychrome seasonal flowers from the Kangxi period, part of the collection at the National Palace Museum in Taipei. The square pot has a straight mouth, a square curved handle, a short spout, and a square arched lid. The lid is decorated with flowers such as roses, chrysanthemums, and narcissus, while the four sides of the plain-body pot are painted with various peonies, lotuses, mallows, and plum blossoms. The Kangxi emperor's personal Yixing-bodied cloisonné enamel tea wares were first produced and selected in Yixing, then sent to the imperial workshops where court artists added cloisonné enamel decorations, which were fired at a low temperature. This pot features bright and vivid enamel colors and meticulous painting, and it is the only known surviving example without a transparent glaze, making it an extremely rare and precious piece of imperial tea ware from the Qing court.

The purple-gold glaze peach-shaped handle pot from the Xuande period of the Ming dynasty, part of the collection at the National Palace Museum in Taipei. It has a small round mouth, a short neck, broad shoulders, and a large belly. It has a short spout and a curved handle. The pot is modeled after natural forms, with a ring of peach branches attached around the body, extending to the spout and handle, giving the spout the appearance of a half-blossomed flower bud. This piece was displayed in the Qianqing Palace, alongside a set of Yixing purple-gold glaze cups, suggesting that it