The history of the Six Great Tea Mountains is half the history of Pu'er tea. On the historical stage of Pu'er tea, the successive Yibang and Yiwu Tusi played different roles. The fortunes and misfortunes of these two families, and the rise and fall of a single tea, were intertwined by fate, together writing an immortal legend.

In the seventh year of the Yongzheng era (1729), the establishment of the Pu'er Prefecture as part of the replacement of local rule with direct imperial administration was a pivotal event that decided the fate of the Six Great Tea Mountains. Following this, Wu Zha Hu and Cao Dang Zhai were successively granted the titles of Tusi by the court, becoming two prominent Tusi families in the history of the Six Great Tea Mountains.

The Cao family Tusi of Yibang and the Wu family Tusi of Yiwu faced complex situations, having to accept the jurisdiction of both the Tusi government of the Che Li Xuan Wei Shi Si and the official government of the Si Mao Office. Ultimately, their fate was determined by the Qing court. As rulers of their respective territories, the Yibang and Yiwu Tusi had to obey orders from above while also ruling those below them. Consolidating their own ruling positions was a constant pursuit for them, which can be seen from their emphasis on their titles. Their efforts to construct a sense of self-identity and status reflected the rise and fall of these two families.

In the eleventh year of the Yongzheng era (1733), the newly appointed Viceroy of Yunnan and Guizhou, Yin Ji Shan, submitted a memorial requesting measures for the aftermath. In his memorial titled “Memorial on the Consideration of the Aftermath of Pu Si Yuan,” he referred to Cao Dang Zhai as the Tusi of Yibang and Wu Zha Hu as the Tusi of Yiwu, indicating military Tusi. This kind of reference was not uncommon.

Statue of Cao Dang Zhai (Yibang Tribute Tea History Museum)

The old street of Yibang, once the seat of the Yibang Tusi, is now the location of the Yibang Village Committee. Not far from the old street lies the cemetery of the Cao family Tusi of Yibang, locally known as the “official tomb hill.” In a recently built golden pavilion, there stands a stele inscribed in the second year of the Qianlong era (1737) by imperial decree, commemorating Cao Dang Zhai and his wife as Zhaoxin Xiaowei and Anren respectively. The inscription clearly states “Cao Dang Zhai, the Tusi of a thousand households of the Yibang tea mountain under the jurisdiction of Pu'er Prefecture, Yunnan Province,” using the official title held by the then Tusi of Yibang, Cao Dang Zhai. The character “Cao” is written with a dot and a horizontal stroke rather than the more common grass radical, a style later referred to as the “officially clear Cao” to distinguish it from the “white-headed Cao.”

(Yibang)

Manzhuan village, once under the jurisdiction of the Yibang Tusi, is now part of the Manzhuang Village Committee of the Xiang Ming Yi Nationality Township of Mengla County (now renamed the Manzhuang Village Committee of the Manzhuan Village). In the home of the tea farmer Feng Jing Tang, there stands a merit stele erected in the sixth year of the Qianlong era (1741) for the construction of the Manzhuan Guildhall, inscribed with “Cao Dang Zhai, the Tusi of a thousand households managing the tea mountains, donated four taels of Silver.” This indicates that the then Tusi of Yibang, Cao Dang Zhai, recognized his title as entirely consistent with his appointment by the court.

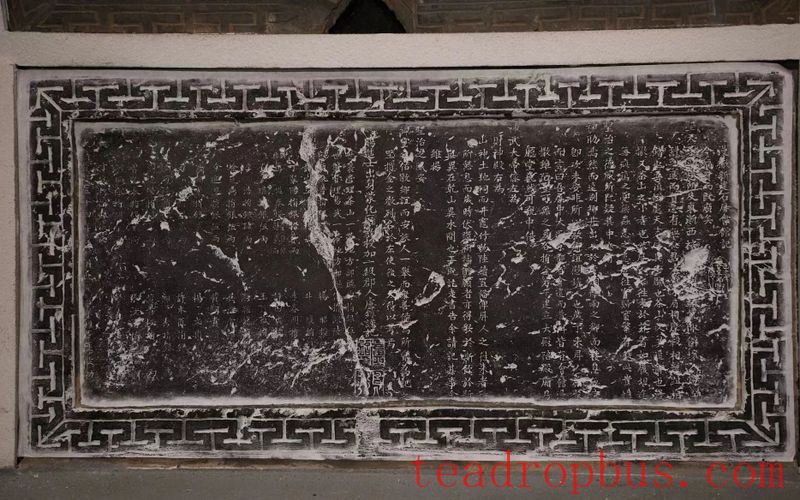

In the twelfth year of the Qianlong era (1747), the then Viceroy of Yunnan and Guizhou, Zhang Yun Sui, issued administrative orders regarding tea policies. The following year, these orders were engraved on a stone stele by the then Tusi of Yibang, Cao Dang Zhai, and his subordinates, and are now preserved in the Yibang Tribute Tea History Museum. For ease of reference, I have named it the “Xu Yi Stele,” without hindering any other naming. The inscription on the “Xu Yi Stele” reads “Cao Dang Zhai, the Tusi of a thousand households managing the tea mountains, with the heads of the four mountains, respectfully established this proclamation.” This shows his respectful attitude and clear understanding of his own position.

In the thirty-eighth year of the Qianlong era (1773), Cao Dang Zhai completed his life, which was full of legendary tales. His tomb is located on the official tomb hill, and the epitaph on the tombstone bears the title “Empress Dowager's Imperial Decree: Zhaoxin Xiaowei, posthumously awarded Wude Lang, the late Cao Gong Dang Zhai.” The reason behind this is that in the thirty-second year of the Qianlong era (1767), Cao Dang Zhai was promoted to the rank of Tushi due to his military merits. Perhaps because of the overall defeat in the Qing-Burmese War, Cao Dang Zhai did not live to receive the corresponding noble title associated with his rank, which became a regret after his death.

In the fifty-first year of the Qianlong era (1786), the content of a license issued by the Yiwu Tusi to guest residents was recorded in “Investigations into the Social History of the Dai People – Xishuangbanna Part Three.” It begins with “The Military Merit Tusi Hall managing the Yiwu area and responsible for money and tea affairs.” This is the earliest known reference to the Yiwu Tusi.

In the fifty-fourth year of the Qianlong era (1789), the new Shansha Guildhall was completed, and the merit stele erected for its construction is now preserved in the Yiwu Tea culture Museum. Among the donors was “Cao, hereditary manager of the tea mountain area, who donated fifty taels of silver,” and “Wu, hereditary manager of the Yiwu area, who donated sixty taels of silver.” This is an interesting fact. As the Tusi of Yibang, donating funds for the construction of the Manzhuan Guildhall in the sixth year of the Qianlong era (1741) was understandable, as it was within his jurisdiction. As the Tusi of Yiwu, donating funds for the construction of the new Shansha Guildhall, which was under his jurisdiction, was also reasonable. However, the then Tusi of Yibang also donated money, and was listed before the Tusi of Yiwu, suggesting that the then Tusi of Yibang and Yiwu had a good relationship and both hoped to display their influence in public affairs related to the tea mountains. Our focus here is on the titles of the then Cao family Tusi of Yibang and the Wu family Tusi of Yiwu, as both began to consciously highlight their symbols of power.

In the second year of the Daoguang era (1822), the ruling made by the then Tusi of Yiwu, Wu Rong Zeng, concerning the dispute between Yiwu and Yibi villages was engraved on a stone stele, now preserved in the Yiwu Tea Culture Museum of Mengla County Yiwu Town. It begins with “Hereditary manager of the Yiwu area responsible for money and tea affairs, Tusi Hall, blank.” There is only a slight difference compared to earlier references.

Approximately after the sixth year of the Daoguang era (1826), the five-province temple in Niuguntang was rebuilt, and the merit stele erected for this purpose is now preserved at the Niu Guntang Tea Tasting Pavilion of the Xiang Ming Yi Nationality Township Anle Village Committee. Among the donors was “Cao, Tusi Hall of Yibang, who donated five taels of silver,” referring to the actions of the then Tusi of Yibang, Cao Ming, actively participating in public affairs within his jurisdiction.

In the sixteenth year of the Daoguang era (1836), the Yong'an Bridge in Yiwu was completed, and the merit stele erected for this purpose is now preserved in the