From September 27 to November 6, 1989, Li Xu, one of the “Six Gentlemen of the Tea Horse Road,” set out from Kunming alone or by hitchhiking and hiking, traveling through Tiger Leaping Gorge – Zhongdian – Deqin – Yanjing – Mangkang – Zuo Gong – Bangda – Baxoi – Ranwu – Bomi – Lhasa – Shannan, arriving in Xigaze, completing the first journey on the Yunnan-Tibet Tea Horse Road.

Graduate students have an opportunity for an “academic visit” before writing their master's thesis, with a research fee of five hundred yuan. I was preparing to head to Tibet. My thesis was about literature and death, a question that had troubled me since childhood. I thought some enlightenment or answers would be found on that road. I had to continue from Lijiang and Zhongdian, following the path once trodden by mule trains. That road haunted my dreams.

In 1986, while working as a lecturer in Zhongdian, I had already traveled extensively around northwest Yunnan, and so I spent all my time thinking about going further. During the summer vacation, I participated in the college entrance examination grading and earned 140 yuan. After piecing together 900 yuan, I borrowed some photographic equipment. My friend Zhang Youlin gave me five rolls of film, making a total of fifteen rolls. Everything was ready, but I couldn't leave, as the school wouldn't let me go.

Finally, I persisted until it was time to set off. Sometimes, all that is needed is persistence.

Passing through Tiger Leaping Gorge, that unforgettable Tiger Leaping Gorge. Back in 1987, I had crossed Haba Snow Mountain with several friends from Zhongdian, traversing it in a single day.

Then we ascended onto the plateau. Familiar sights greeted me again: Tibetan houses, prayer flags, yaks, bright red poison wolves, and vast fields, evoking a myriad of emotions. It had been a long time, plateau.

I bought a ticket to Deqin in Zhongdian, as the long-distance bus only went that far. The long-held wish had finally been put into action. True wandering, true silence, true solitude. What more could I ask for?

It took a full ten hours to reach Deqin. I really wanted to hike, which might have felt better. Upon arrival, I hurried to find a vehicle. Eventually, I managed to get a ride on an old truck from Tibet's Changyu region, loaded with large crates. There were two fellow travelers: Xiao Chen from Guangxi, who had quit his job to travel without any particular purpose, and a man from Hong Kong with a Silver earring in his right ear. I later discovered he was a cannabis user. For him, life probably revolved around places where cannabis grew.

The Prince Snow Mountain was obscured by clouds and mist. Along the way, there were frequent landslides and slope failures, forcing us to repeatedly get out of the vehicle to dig paths and push it along. My intestines almost came out. Fortunately, the Tibetan drivers were bold. They were accustomed to all the hardships on the road, and people from other regions would have faltered long ago. Gradually, the trees disappeared, leaving barren mountains and murky rivers. We arrived at Yanjing at night, which felt like a small American Western town from the 19th century.

We knocked on the door of the only accommodation available, the Supply and Marketing Cooperative Guesthouse. It resembled a medieval abandoned ruin. As soon as we stepped inside, thick dust enveloped our shoes. There was no water or light, and a staff member shone a flashlight to show us our beds. Each bed cost three yuan. In the dark, we ate some bread and tsampa and slept in filth.

Leaving Yanjing for Mangkang, the autumn scenery was pleasant. Red became redder, yellow became yellower, and green remained green. The colors were vivid and saturated. The Tibetans in Mangkang had a strong ethnic flavor. The vehicle broke down in Mangkang, and I walked with several Tibetan companions. Along the way, we listened to them recite scriptures and sing songs, not feeling tired. A few days later, we reached Zuo Gong. Zuo Gong is a clean little city located in a river valley.

Snow had begun to fall on the mountains. After waiting for two days without any vehicles, we continued on foot. The mule trains of old also followed this route, although Zuo Gong was not yet a county seat at that time. Our group had grown, including an elderly monk heading to Lhasa to fulfill his wishes, two young women who mainly gathered firewood to make tea, and two children who had run away from home and were also going to Lhasa to worship. I didn't understand why they chose to endure such hardship on the road. Perhaps they didn't understand me either. With a language barrier, we could only communicate through gestures. Sometimes, a glance was enough.

When we arrived in Bangda, the broken-down truck from Changyu caught up, and we climbed into its cargo area. Over the course of half a month, this was likely the only vehicle on this highway. The difference was that there were now two and a half adult yaks in the back. Whenever the vehicle swayed, they would lean on us, and their hooves couldn't maintain their balance. We had already taken on the smell of yaks and butter tea.

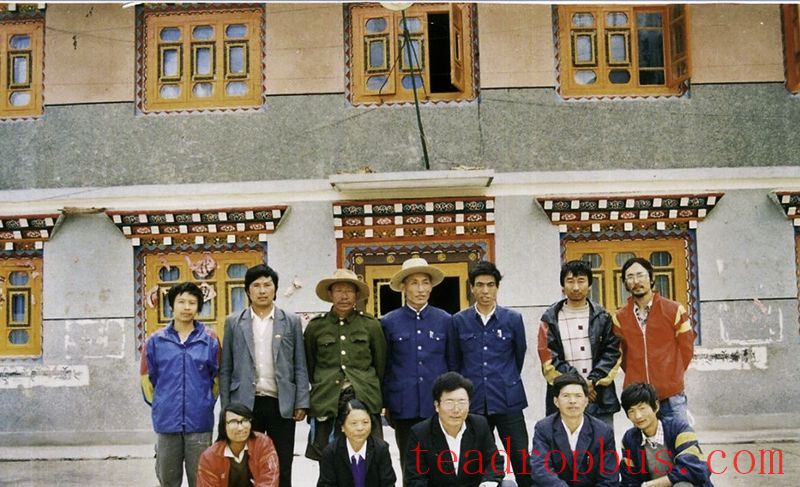

The “Six Gentlemen of the Tea Horse Road” took a commemorative photo with local ethnic and cultural workers during their exploration of the Tea Horse Road.

As soon as we left Bangda, we headed uphill, where the snow was thick, and the vehicle moved with difficulty, groaning with every step, crawling along. It often skidded and stalled, and we had to push and dig in the snowstorm. Or walk. Every groan of the vehicle made us worry that it would break down on the mountain. Just a hundred meters from the pass, it did indeed break down. We nearly froze at the mountain pass. After much effort, we finally passed over it, sliding downhill. The headlights carved colorful light trails in the snowy night sky. When the beams hit the sparkling snow, they fully displayed the texture and luminosity of the snow, which was incredibly beautiful. At midnight, the vehicle slid halfway down the slope and stopped moving, requiring repairs. We gathered firewood and started a fire, huddling around it to stay warm through the night.

After repairing it for half a day, we finally descended into the Nu River Valley and reached Baxoi. The roads were extremely dangerous, with countless hairpin turns. The canyon and the river were imposing, and I kept looking from the back of the truck. Crossing the steel bridge over the Nu River, soldiers on guard checked our IDs. The truck needed repairs in Baxoi (Baima), and we had to find a way to refuel. It was said that we needed the county magistrate's approval. So, like the Tibetans, we wandered up and down the muddy streets, looking at the same small items in each shop. Looking at them, I couldn't help but laugh. On that day, I probably became familiar with all the biscuits, canned goods, rubber shoes, and people in the entire city. The two Tibetan children who had run away from home had more than tsampa and Tibetan knives in their pockets; they probably also had twenty yuan.

This was their first time in the city, and they stuffed themselves with various delicious foods, turning green-faced and clutching their stomachs when we saw them today. I offered them some berberine tablets, gesturing for them to take them. They had probably never encountered such things before, putting them in their mouths and chewing. Instantly, their mouths opened wide, their mouths turned yellow, and their faces showed a bitter expression. When I saw them again that evening, they were laughing and smiling, giving me a thumbs-up. I wandered around nearby villages. The lamasery had been burned down and was being rebuilt. I took some photos of the ruins and the unique cantilever wooden bridges typical of the Tibetan region over swift rivers.

The scenery along the way from Baxoi to Ranwu was magnificent, with blue skies, white clouds, silver snow, and clear waters… After passing the perilous Ranwu Gorge, icicles hung almost to the top of the vehicle, and in some places, trunks were used to build roofs. Ranwu Lake formed after an earthquake caused a blockage in the Palong Tsangpo River. Sur