Recently, the TV series “Blossoms,” created by renowned director Wong Kar-wai, has been a hit. In just over half a month, it has achieved remarkable ratings, further boosting the popularity of “Metropolis” Shanghai.

“Blossoms” poster

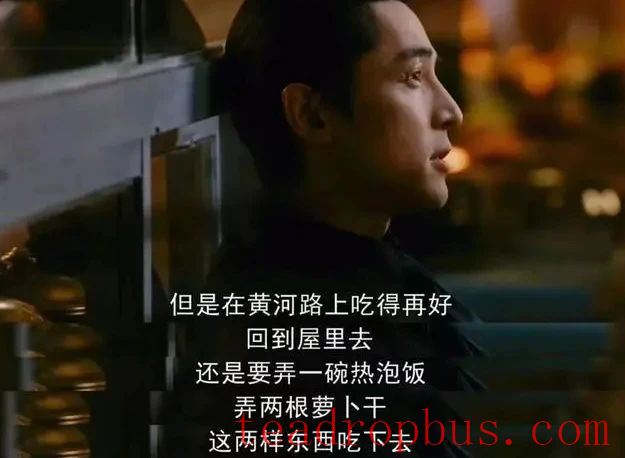

The series is not only visually appealing but also tantalizes viewers with its depiction of Shanghai cuisine, including dishes such as pork rib and rice cake, The Conqueror's Farewell, Captain's Fried Rice, porridge, dry-fried beef noodles, Ding Sheng Cake, and fried dough balls, among others, leaving internet users drooling.

In fact, the original novel (2012) by Jin Yucheng also captures the taste of old Shanghai through its descriptions of Tea.

The human touch of “having tea”

Both the novel and the TV adaptation are filled with authentic Shanghai dialect, vividly portraying the city's life to readers and viewers alike. When Wong Kar-wai, who was born in Shanghai and left for Hong Kong in the 1960s, acquired the rights to adapt “Blossoms,” he described it as “Shanghai's version of ‘Along the River During the Qingming Festival,' representing the essence of Shanghai.”

Jin Yucheng also mentioned that dialects carry a unique flavor, embodying the distinct character of a region. There is a passage in the original:

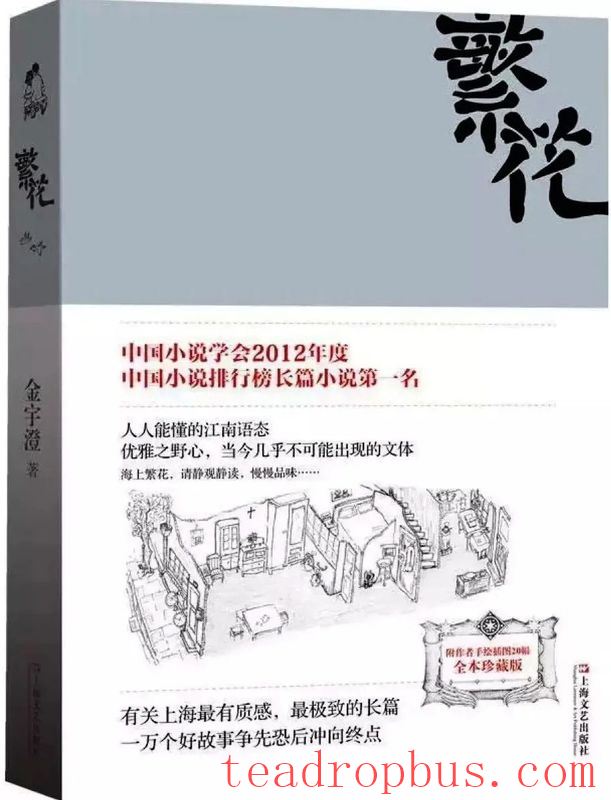

“Hu Sheng passed by the Jing'an Temple market and heard someone calling out. Hu Sheng looked and saw Tao Tao, a neighbor of his ex-girlfriend Mei Rui. Hu Sheng said, ‘Tao Tao is selling hairy crabs now.' Tao Tao replied, ‘It's been a long time; come in for a cup of tea.' Hu Sheng said, ‘I have something to do.' Tao Tao insisted, ‘Come in, come in to enjoy the scenery.' Hu Sheng reluctantly entered the stall…”

The noted writer Shen Hongfei annotated: “In old Shanghai dialect, ‘tea' generally refers to boiled water, while tea with leaves is called ‘leaf tea.' Readers from other provinces should take note of this distinction.” (From “Blossoms: Annotated Edition,” Changjiang Literature and Art Press)

The explanation of “tea” in old Shanghai dialect from “Blossoms: Annotated Edition”

The common phrase “Have tea when you're free?” is an invitation among friends, conveying a warm sense of camaraderie. Additionally, there is the custom of “having tea to resolve disputes.”

In old Shanghai, if neighbors had conflicts, they would go to a Teahouse to “have tea to resolve disputes,” inviting respected elders or individuals with social influence to mediate and speak on their behalf.

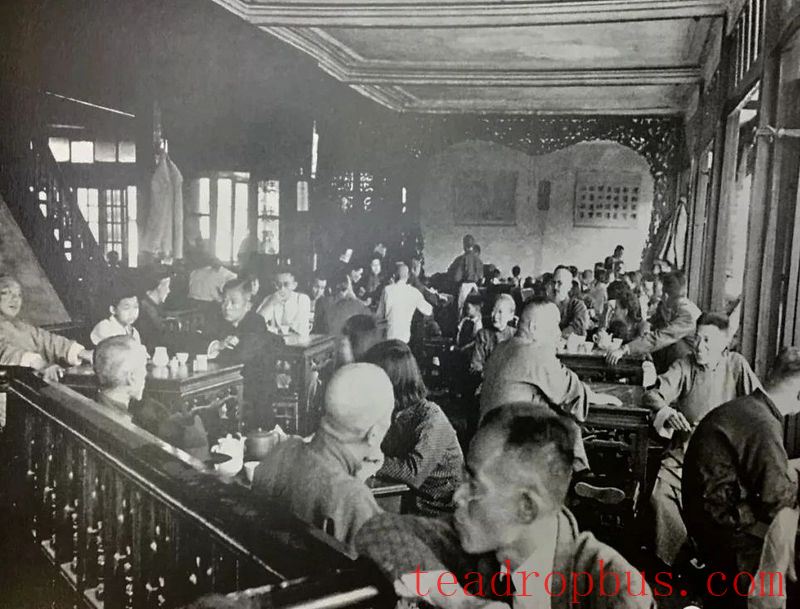

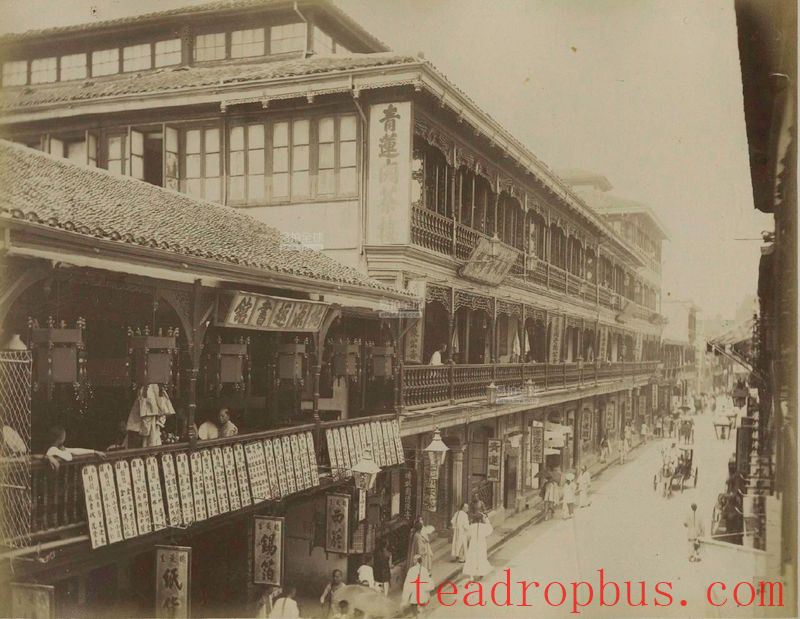

An old Shanghai teahouse

Typically, the party at fault would apologize and cover the cost of tea for everyone present, bringing a happy resolution to the matter.

The charm of old teahouses

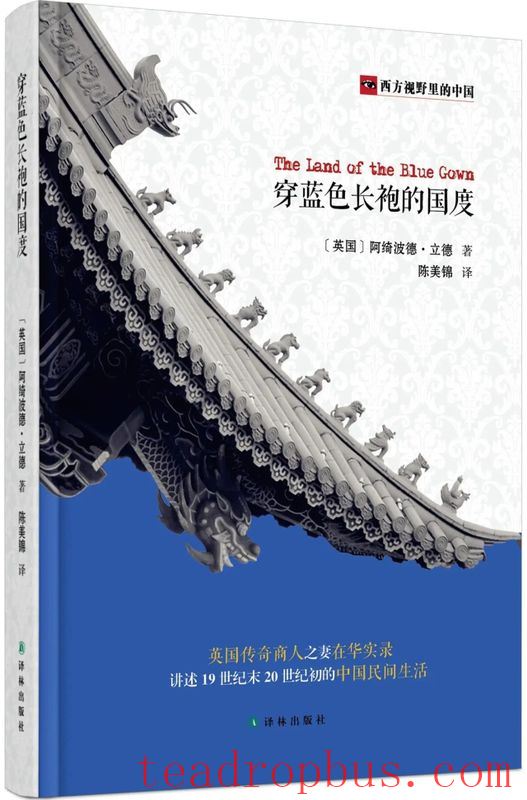

In her book “The Land of the Blue Robe,” British merchant Archibald Little's wife, who lived in China for twenty years, wrote:

“One of the best things about Shanghai is its teahouses. They look like pictures on English willow-patterned plates, with water, bridges, pavilions, and artificial mountains. These bridges twist and turn, one here, one there, very delicate.”

Archibald Little and his wife, along with “The Land of the Blue Robe”

Teahouses represent the refined urban atmosphere of old Shanghai. According to Xu Ke's “Miscellaneous Records of Qing Dynasty: Tea Shops,” “The first teahouse in Shanghai was Lishuitai, built in the third year of Tongzhi near the riverbank of Yangjing Bang. It had three floors and spacious buildings.”

Following Lishuitai, teahouses spread from the southern part of the city to the north. Teahouses with poetic names such as Yitiantian, Hutin Pavilion, Yilan, Guifang Pavilion, Xiangxuehai, Hongfoulou, Yihuchun, and Deyilou opened one after another.

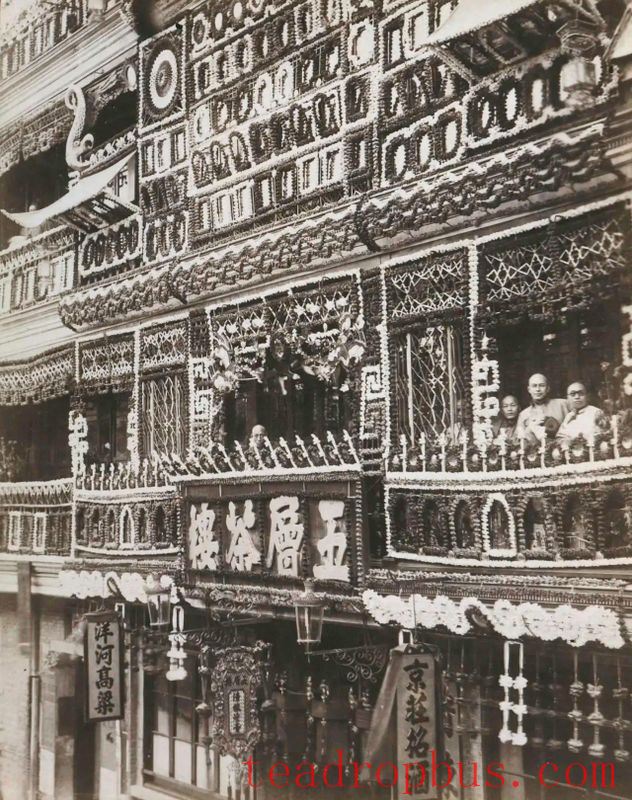

A five-story teahouse in Shanghai during the late Qing Dynasty

By the first year of the Xuantong era (1909), there were around sixty teahouses in Shanghai, increasing to over 160 by the 1920s. At the time, teahouses were everywhere in Shanghai, bustling with customers and filled with the aroma of tea.

Old Shanghai was a city where diverse cultures mingled, and the styles of teahouses varied widely, including Suzhou-Zhejiang flavors, southern Chinese styles, Japanese, European, and more.

Qingliange Teahouse in Shanghai

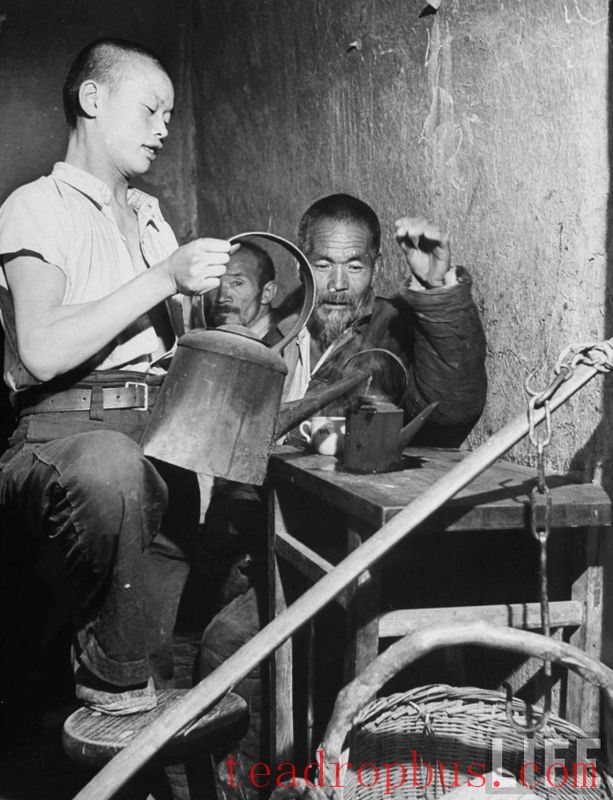

Teahouses were also categorized based on the status of their patrons, ranging from high-end to low-end. High-end teahouses were typically located in bustling areas or scenic spots, frequented by officials, socialites, scholars, and other elites. Low-end teahouses were scattered throughout residential areas, serving ordinary people. A typical example was the “tiger stove,” where laborers would rest after work, enjoying a cheap pot of hot tea while chatting, feeling content.

Ordinary people resting and having tea at a teahouse

The most famous and oldest existing teahouse in Shanghai is undoubtedly the Hutin Pavilion Teahouse. Originally built by Pan Yunzhu, a Sichuan provincial governor during the Ming dynasty's Jiajing period, it was part of the Yu Garden. Since 1855, it has operated as a teahouse, initially named “Yeshixuan” and later renamed “Wanzai Xuan.”

This historic teahouse features upturned eaves, dark tiles, and red windows, standing in the middle of the Nine-Bend Bridge pond. Its interior spans two floors, adorned with redwood furniture, calligraphy and paintings on the walls, and lanterns hanging from the ceiling, creating a tranquil environment. Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom visited and had tea here during her trip to China in 1986.

Hutin