Identify the Author

Lu Yu (733–804 AD): Also known as Ji, with the courtesy name Hongjian, and another name Jici. He referred to himself as the Mulberry Man and was also known by the pseudonym Donggangzi. He was a native of Jingling, Fuzhou (today's Tianmen, Hubei Province), in the Tang Dynasty. Lu Yu is said to have been an abandoned infant adopted and raised by the Zen Master Zhiji from Xita Temple in Tianmen.

In his youth, Lu Yu's master taught him Buddhist scriptures, but Lu Yu was unwilling to learn them. His master became angry and punished him with hard labor, yet Lu Yu continued to study diligently. Later, he escaped from the temple and joined a troupe of actors.

During the Tianbao period of the Tang Dynasty, local officials in Tianmen held a banquet and called upon Lu Yu's troupe to entertain. The Prefect of Tianmen, Li Qiwu, admired Lu Yu and gave him some poetry books. Thus, Lu Yu studied under Master Zou on Huomen Mountain near Tianmen.

Later, he was recognized by Cui Guofu, a former Ministry of Rites official who served as a Macao in Tianmen, who gifted Lu Yu a “Literary Scholar's Cassia Letter” and a “Black Ox Cart.” Despite his unappealing appearance and stammer, Lu Yu was well-versed and good at debate, with a generous and trustworthy personality.

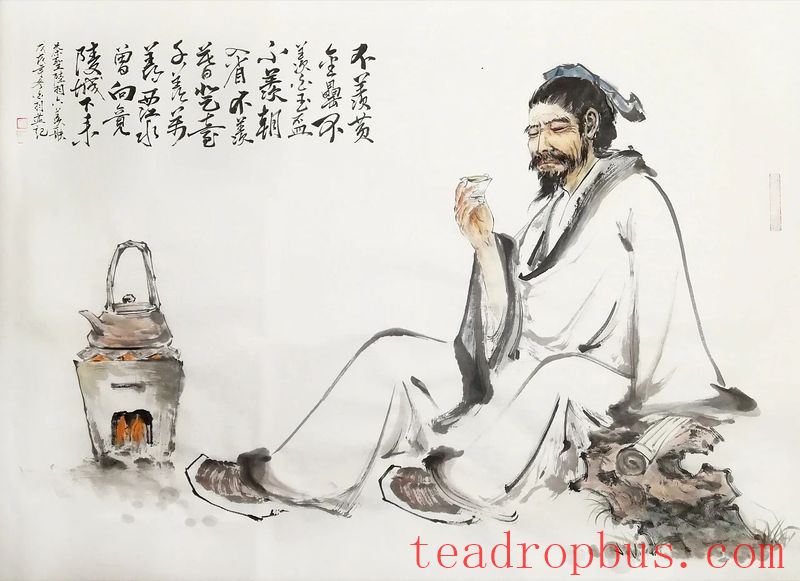

In the early years of the Shangyuan era of the Tang Dynasty, Lu Yu lived in seclusion in Wuxing, Zhejiang, where he secluded himself to read and referred to himself as the Mulberry Man. He only socialized with famous monks and scholars, drinking, reciting poems, and exchanging verses. He formed a deep friendship with the monk Jiaoran. Sometimes, Lu Yu would wander alone in the wilderness, reciting poems, and even weep before returning home.

After a long time, the emperor issued an edict appointing Lu Yu as a “Literary Scholar for the Crown Prince,” and later as a “Great Tutor for the Crown Prince,” but Lu Yu did not accept these positions. At the end of the Zhenyuan era, he passed away at the age of seventy-two.

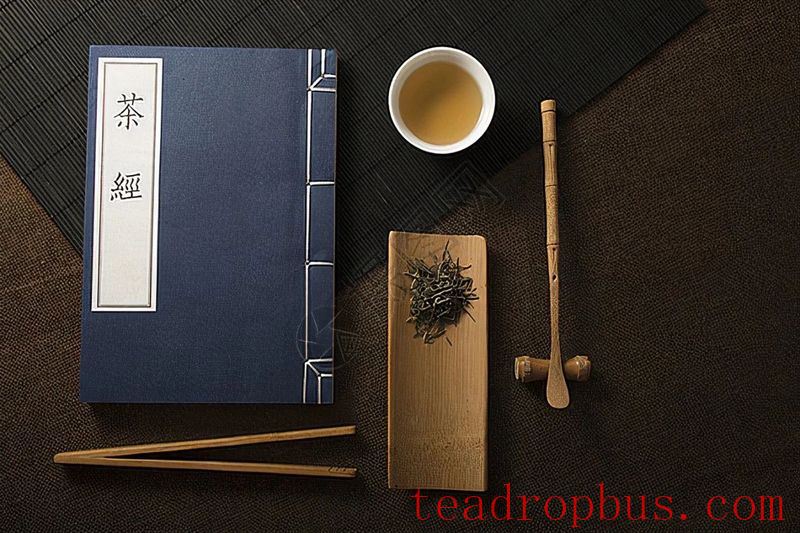

Lu Yu had a particular fondness for researching Tea and wrote “The Classic of Tea,” a three-volume work that meticulously detailed the origins of tea, its cultivation, preparation, consumption methods, and the tools used for making and brewing tea, thus enlightening the entire nation about the benefits of tea. Although many of Lu Yu's other works are now lost, “The Classic of Tea” has remained intact and passed down through generations. Posthumously, people revered him, placing ceramic statues of Lu Yu on altars in tea shops, worshipping him as the “Tea God.”

Read the Poem

The Song

I do not envy the golden flagon,

Nor the white jade cup.

I do not envy those entering the palace in the morning,

Nor those entering the imperial offices in the evening.

I envy the waters of the Western River ten thousand times,

For they have flowed down to the city of Jingling.

Savor the Meaning of the Poem

I do not desire a golden flagon,

Nor a white jade cup.

I do not envy the high officials who freely enter the palace,

Nor the eminent figures in politics.

I only envy the waters of the Western River,

Flowing ceaselessly towards the city of Jingling.

This poem, “The Song,” was composed in the sixth year of the Zhenyuan era of Emperor Dezong during the Tang Dynasty, while Lu Yu was residing in Shangrao, Jiangxi. It is said to be a tribute to Zen Master Zhiji. According to the supplement “Tea Scholar” (Volume I): “When Lu Yu was elsewhere and heard of his master's passing, he cried bitterly and composed a poem to express his feelings…” This poem reveals Lu Yu's tranquil aspirations and noble character, showing that he does not covet wealth or glory; what he truly envies is the water of the Western River flowing towards his hometown.