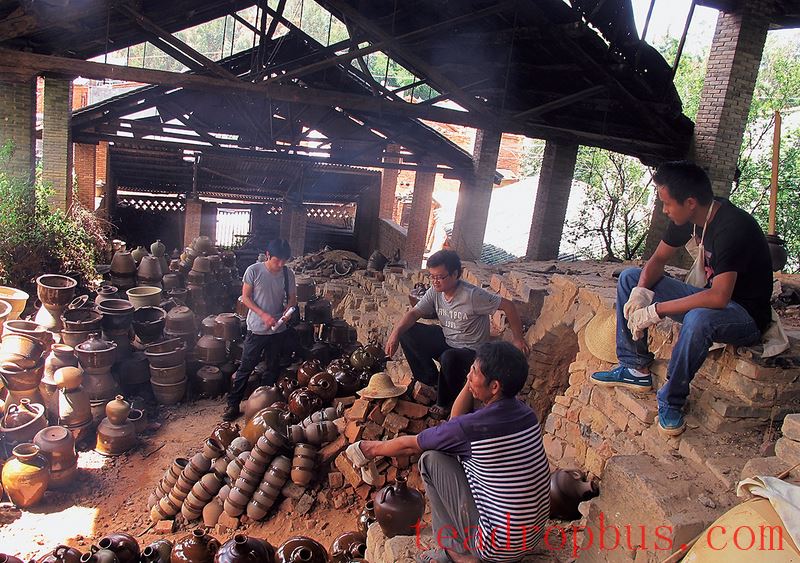

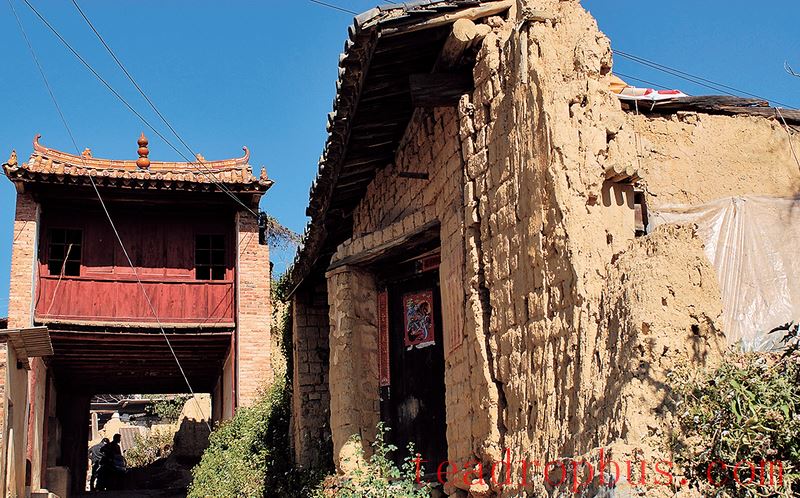

The rain pattered in the courtyard as dusk fell into midnight. This was the first rain of winter in Jianshui, and Pottery makers dread the cold season. Even half-dry clay pieces feel like immovable ice blocks, and more importantly, it takes twice as long for clay to dry enough to be fired in the kiln compared to summer or autumn. Perhaps the unforgiving nature of the clay and the slow passage of time could inspire a greater sense of respect and care. I looked forward to the earth in my hands retaining the essence of a Jianshui winter after its transformation.

My friend Master Muzhong's mother called me to dinner. It was just her and me in the small courtyard. After finishing her prayers, she had made the journey from the old house in Shangyao to the workshop in Xiayao to cook for me. I stretched and put down my carving knife, carefully wrapping each unfinished piece of clay in plastic bags and placing them on an old wooden table that had lost its paint. The kitchen was to the left of the courtyard, and raindrops rolled off the tiles, forming shimmering Silver threads that appeared and disappeared.

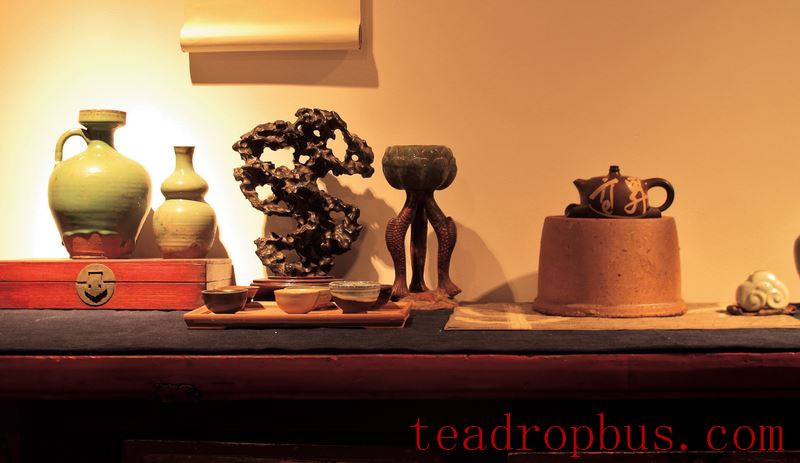

The rural kitchen was small to begin with, and most of its space was taken up by stored clay. Apart from the stove, there was barely room for two or three people. The kitchen light, covered in droplets of rainwater, cast a warm yellow glow, mixing with the steam rising from the tofu and vegetable soup and fried local eggs on the stove, creating a cozy atmosphere. I sat on a small stool, needing to sit up straight to see my food, while at eye level were bowls decorated with blue-and-white Peony and fish patterns painted by Jianshui potters. The lines were firm and lively, full of vibrant energy.

I have a great love for Jianshui blue-and-white ware. I've always felt that the dots and lines on Jianshui blue-and-white bowls are reminiscent of the brushwork style of Han and Wei folk calligraphy, even resembling the characters in the Yumen Sleeping Tiger Bamboo Slips. In terms of brushwork, this style likely dates back before the era of Wang Xizhi and Wang Xianzhi. Its color is not as vivid as Su-ma-li-qing; rather, it is a simple bluish-brown, like distant mountains, serene and tranquil.

As I ate, I admired the bowl in my hand, praising it sincerely. Many years ago, an older generation potter told me that the brushes used to paint Jianshui blue-and-white are made from the fine hairs of a local dog's neck, and they must be from Jianshui. According to “Essential Records of Calligraphy,” “Wang Xizhi wrote the Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Gathering using a brush made from mouse whiskers, which he received from Mr. White Cloud.” “Notes on Dongpo” states, “I wrote the Moon Pagoda Inscription using a brush made from mouse whiskers, Chengxin Hall paper, and ink by Li Tinggui, all selected choices of their time.” Both Wang Xizhi and Su Dongpo produced masterpieces with brushes made from mouse whiskers. Though not a calligrapher myself, I have since always used a brush made from dog hair to paint blue-and-white designs. I believe that all beauty is given by nature and heaven, and without the local environment and human touch, it is impossible to create true living beauty.

I often asked the potters who painted flower vases at the factory how they learned such exquisite skills. Some told me that when they were young, they thought the bowls at home were beautiful and learned to paint them as they grew up. Others mentioned that while working in the fields, they saw grass swaying in the wind and wanted to paint it onto jars and vases. I marvel at how easy it is in the southern reaches of Yunnan, in the countryside of Wanyao Village, to encounter the beauty of tradition and the truth of nature. These rural women, preoccupied with firewood, rice, oil, and salt, become extraordinary artists when they touch Jianshui blue-and-white. I admire and praise their works as much as I would appreciate the charm of Tang tri-color ware or the elegance of Song dynasty porcelain. I firmly believe that the essence of Chinese Ceramic tradition lies not in the titles of “masters” or the works of “academic” ceramic artists, but quietly within the hands of these craftsmen.

Most of these women have not received formal education and do not know what “art” truly means. They simply work day after day, treating their neighbors kindly. They rise with the sun and rest at sunset. They are ordinary, low-key, and simple people, and the flowers they paint are also ordinary, low-key, and simple. Their innate talents and temperaments are natural and humble, like clay. They have not been transformed by so-called “art”; painting flowers is as commonplace for them as planting rice, fetching water, cooking, washing clothes, breastfeeding. The beauty in their brushstrokes is natural, everyday, living, and ordinary. They don't even think about leaving their names on their works, believing themselves to be the most ordinary and common people in the world. The important traditions and virtues of ancient Jianshui permeate their lives.

Unfortunately, contemporary Chinese art has degenerated into vulgar commercial gimmicks. Morality, cultural education, and monetary gain are intertwined, and there is a relentless pursuit of novelty and uniqueness, hoping to gain respect, nobility, and prominence through these means. Living in bustling cities, we have lost the ability to recognize ordinary beauty and be ordinary people. We fear not being praised and worry about becoming ordinary. In this world, ordinary things, ordinary people, and the virtue of kindness and traditional normalcy cannot escape contempt! Only extravagant displays of wealth and extraordinary appearances can beg for respect from others and oneself. Do we still have ordinary things and ordinary people around us? Can we still receive the teachings of ordinariness, simplicity, and normalcy? I am reminded of the dialogue between Chan Master Zhaozhou and Master Nanquan:

“The master asked Nanquan: ‘What is the Way?' Nanquan said: ‘An ordinary mind is the Way.' The master asked: ‘Can one aspire towards it?' Nanquan replied: ‘If you try to aspire, you miss the mark.' The master asked: ‘Without aspiring, how do you know it is the Way?' Nanquan replied: ‘The Way does not belong to knowing or not knowing; knowing is delusory perception, and not knowing is non-recollection. If one truly reaches the Way without doubt, it is like boundless space, vast and empty, how can one forcefully make distinctions of right and wrong?' The master suddenly understood the profound meaning, his mind like a bright moon.”

Today, traditional Jianshui blue-and-white ware is hard to find, and fewer women know how to paint flowers. The tranquility of Wanyao Village has been torn apart by the neon lights of the new city, much like an unsophisticated country child forced to mature in