The history of Jingdezhen's colored glaze porcelain is long and renowned both domestically and internationally. It can beautify ceramics as well as people's lives. Poets and scholars from all times have admired the colored glazes of Jingdezhen, describing them as “green like spring water on the day it emerges, red like dawn breaking at sunrise.” “As bright as the waters of southern Jiang in spring, as pure as the ice of northern lands.” Some describe the enchanting colors of the porcelain capital with phrases like “the changing colors of the kiln resemble rolling waves,” “red glaze is like a beauty drunk,” “variegated glaze changes endlessly,” and “celadon glaze is clear after the rain.”

As one of the four traditional famous porcelains of Jingdezhen, colored glaze porcelain has always been highly regarded. It is made using various metal oxides and natural minerals as coloring agents, which are then applied to the body and fired at over 1300°C. The kiln position requirements are extremely strict, especially for some precious colored glazes, there is a saying that “an inch of gold kiln produces an inch of gold porcelain,” hence its reputation as a “man-made gemstone.”

The outstanding achievements of colored glaze porcelain are the result of the hard work and wisdom of our people and are one of the valuable cultural legacies of our country; they have made significant contributions to the exchange of world science and culture.

I. The Beauty of Colored Glaze Decorated Porcelain

The variety of colored glaze porcelains in Jingdezhen is extensive, with vibrant colors. In terms of classification, there are those classified by firing temperature, by the melting properties of the glaze, and so on.

There are many types of high-temperature colored glazes, nearly a hundred with specific names, which can be generally divided into the following systems:

1. Red Glaze System including sacrificial red, Jun red, Lang Yao red, underglaze red, drunken beauty, flame red, Rose purple, etc., primarily colored with copper.

2. Celadon Glaze System including sky celadon, Longquan celadon, pea celadon, translucent celadon, powder celadon, plum celadon, jade celadon, Tea celadon, winter celadon, duck egg celadon, etc., primarily colored with iron.

3. Blue Glaze System including stormy blue, faience blue, stormy celadon, etc., primarily colored with cobalt.

4. Others include changing variegated glazes, Song Jun variegated glazes, purple gold glazes, black gold glazes, tea leaf glazes, eel yellow, ancient bronze green, emerald green, faience green, faience purple, etc., which are colored by mixing various materials.

Although the colors of the colored glazes are striking and captivating, their production presents great difficulties: the firing is very unstable, and obtaining a flawless and satisfactory finished product is exceptionally difficult. Even if the exact same formula is used with the same thickness of colored glaze, if the placement in the kiln is slightly different, the color effect after firing will be almost unrecognizable.

From this, we can see that the technical and manual requirements for colored glazes are relatively high, and the presentation of their colors and varieties are unpredictable and numerous. Among all colored glaze porcelains, the most precious are sacrificial red, drunken beauty, and Three Yang Open.

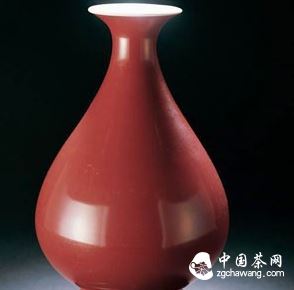

Sacrificial red is one of the outstanding products of traditional Chinese porcelain. It is a jewel among high-temperature colored glazes. Qing dynasty scholar Xiang Kangbian (Compendium of Named Terms Through the Ages) wrote: “Sacrificial red, its color is as brilliant as crimson clouds, truly the foremost of all named porcelains through the ages!” Its glaze features a red that is not too harsh on the eyes, fresh but not overly so, the glaze does not run, and no cracks appear. It has many aliases, such as “stormy red,” “chicken red,” or “extreme red,” but these are all referring to the same variety. Since they are all colored with copper oxide and are fired once, their appearances are not too dissimilar, so people often mistakenly take “Lang Yao red” for “sacrificial red.”

Throughout history, “sacrificial red” has been one of the most challenging varieties to produce. However, upon close examination, there are significant differences between “sacrificial red” and “Lang Yao red” in terms of tone, glaze characteristics, and firing temperatures. For example, “Lang Yao red” displays an extremely vivid red color, with high transparency and large, open cracks. There is a slight running of glaze on the upper part of the piece. On the other hand, the red of “sacrificial red” is deeper, the glaze surface has no cracks, no luster, and no running. Both the rim and base have a wick-like edge. Producing a successful “sacrificial red” porcelain today is already quite difficult, let alone in ancient times when scientific and technological advancements were far behind. Nevertheless, in formulating “sacrificial red,” ancient craftsmen spared no expense. Materials like coral, carnelian, ice stones, pearls, and even gold were sometimes added to the mix. Despite this, the firing success rate remained low. Even with good formulas, if the firing conditions were unsuitable, entire kilns of porcelain could turn out as waste. This is because the firing of “sacrificial red” remains an art of fire. Today, there are still many new research topics related to “sacrificial red” that await technical experts to explore and solve.

Drunken beauty is the most vivid tone among peach blossom pieces. Its tone contrasts with Jun red, sacrificial red, Lang Yao red, and other copper reds. In most cases, it is not a deep red but rather a light red, resembling the hues of peach blossoms and crabapple flowers, hence it is also called peach blossom pieces and crabapple red. Additionally, there are terms like drunken stormy and drunken sacrificial, but they all refer to the same variety. As someone once described the glaze color of drunken beauty with Hong Liangji's poem about apples, “Green like spring water on the day it emerges, red like dawn breaking at sunrise.” Due to the particularly difficult firing process, samples of drunken beauty are mostly small vessels. Even so, truly excellent samples, whether ancient or contemporary, are rare. As Qing dynasty poet Gong Shi noted in his “Jingdezhen Ceramic Songs,” “Official ancient kilns emphasize stormy red, the most challenging to achieve, requiring skilled labor. Under clear skies, they carefully combine elements, yet a hundred differently shaped pieces emerge from the same firing.”

Three Yang Open is one of the prestigious varieties of high-temperature colored glazes in China. It is based on a black tone, complemented by red, resembling flickering red clouds, beautiful and extraordinary. The colors are balanced, with primary and secondary tones. The distribution and pairing of the colored glazes on the vessel also consider the shape and characteristics of the glaze. At the top of the vessel, the fluidity of the red glaze creates a band of celadon hue, giving the entire vessel a sense of ease and openness. In fact, this is a natural result of the firing process. Without this lighter band at the top, the entire vessel and its colors would seem dull. Upon closer inspection, there is a lighter bluish-green hue where the red and black glazes meet on the neck of the flat-bellied vase, blending naturally and harmoniously without any sense of forcedness. The red seeps into the black, lively and dynamic, yet natural and smooth. Although the colors are rich and varied, changing endlessly, they blend together harmoniously