In the previous topic, we explored the significance of enzymatic reactions and microbial activities in Pu'er Tea. Indeed, one of the greatest advantages of Pu'er tea production methods is the utilization of various microbes' differing oxygen requirements, dividing fermentation into aerobic and anaerobic processes, also sometimes referred to as pre-fermentation and post-fermentation.

The reason for distinguishing between these two types of fermentation is that the microorganisms involved in Pu'er tea fermentation can be divided into aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, each with a specific role.

Functionally, aerobic fermentation primarily handles the biological oxidation of the compounds within Pu'er tea, while anaerobic fermentation breaks down complex organic compounds into simpler substances, complementing the work of aerobic bacteria.

In terms of their targets, aerobic fermentation mainly acts on raw tea leaves. Once the tea leaves are compressed into shape, only the surface remains exposed to air, while the interior becomes an oxygen-deprived environment, creating conditions for anaerobic fermentation. This is also why it's not recommended to store loose tea with long-term exposure to the air.

After gaining a basic understanding of the principles of Pu'er tea fermentation, we can now proceed to analyze the Pu'er tea production process step by step, following a clear main thread: everything is done for the sake of fermentation.

From the moment we pick fresh leaves from Yunnan's large-leaf tea trees, the aerobic fermentation of Pu'er tea begins and will run through the entire initial processing phase, including picking, withering, kill-green, rolling, and sun-drying, among others.

“Enzyme Preservation” and “Enzyme Destruction”

Freshly picked leaves contain a high amount of water and are very tender. They need to be stacked up to 10 centimeters high and laid out in a withering trough. The ideal temperature during withering should be maintained between 23°C and 29°C, and the duration should not exceed 24 hours, as this could trigger premature fermentation, causing the leaves to turn red, known colloquially as “red change.”

Generally, withering is considered to allow natural dehydration of the fresh leaves to achieve a soft, shriveled state. However, more importantly, withering activates the enzymes in the fresh leaves, degrading some of the chlorophyll, clearing the way for subsequent fermentation.

Following withering, the next step is kill-green. Both Yunnan Pu'er tea and Green Tea use pan-firing, but the techniques differ significantly. This is mainly because Yunnan Pu'er tea requires fermentation, whereas green tea does not, leading to different approaches summarized as “enzyme preservation” and “enzyme destruction.”

To achieve the “three greens” (green color, green infusion, and green leaf base), green teas often use high-temperature pan-firing with leaf temperatures exceeding 75°C. The process often involves more smothering than tossing and may even include “re-frying” to completely destroy the activity of polyphenol oxidase, preventing the degradation of chlorophyll and blocking further fermentation, ensuring a bright green appearance and a high aroma.

Pu'er tea, on the other hand, is more complex. During kill-green, it is necessary to destroy most of the polyphenol oxidase activity to prevent excessive oxidation of polyphenols while preserving some enzyme activity to avoid a “grassy” or “Black Tea” aroma, allowing for proper post-fermentation.

In addition, the kill-green process in Pu'er tea serves to further degrade chlorophyll (ensuring a bright yellowish hue in the infusion and a fresh green appearance in the leaf base), eliminate the grassy smell (ensuring the emergence of tea aroma), and evaporate moisture (making the leaves soft and easier to roll into shape).

Technical Points for Kill-green

Kill-green is not only important but also relatively challenging, with temperature control being the most difficult aspect. This is because the enzymes in fresh leaves are highly sensitive, and their activity changes continuously with the temperature of the leaves.

If the temperature during kill-green is insufficient, the protein structure of the leaf enzymes will denature and solidify, enhancing the activity of polyphenol oxidase and leading to enzymatic oxidation. This causes the originally colorless polyphenols to convert into red oxidation products, resulting in “red stems and red leaves.”

If the temperature is too high, the proteins in the leaf enzymes will solidify more quickly, completely losing their activity, transforming the process into that of green tea. The tea leaves may develop burn marks, spots, or even become charred, known as “smoky burnt tea.”

The general pattern is as follows:

When the leaf temperature is greater than 20°C, the activity of the leaf enzymes gradually increases;

When the leaf temperature reaches 40°C to 45°C, the activity of the leaf enzymes reaches its peak;

When the leaf temperature exceeds 45°C, the activity of the leaf enzymes gradually diminishes;

When the leaf temperature is above 65°C, the activity of the leaf enzymes is virtually lost.

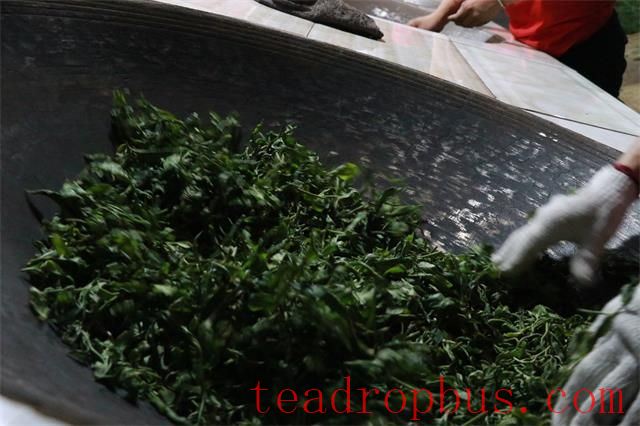

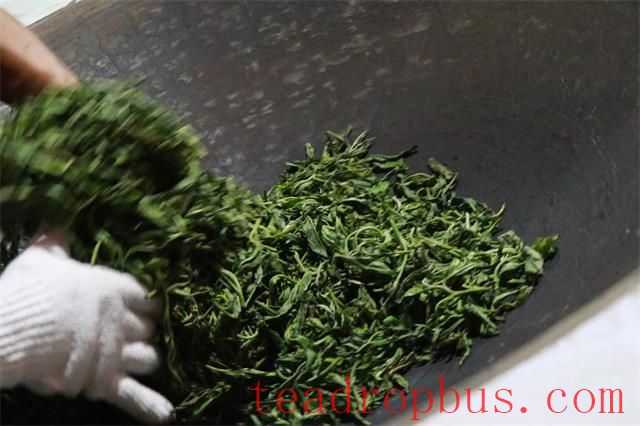

Therefore, to achieve the appropriate temperature, the temperature of the pan used for manual kill-green in Pu'er tea is generally controlled below 180°C. In the past, few people would specifically measure the temperature of the pan, relying instead on experience.

There is a saying about observing the temperature of the pan: “grayish in daylight, dark red at night.” More experienced masters would listen for the sound of the temperature when the fresh leaves hit the pan. If they do not hear the popping sound of the leaves in the pan, there is a high probability of red stems and red leaves, and a grassy flavor.

Moreover, the climate, rainfall, grade of tea leaves, and quality of the tea vary from year to year, so manual kill-green must adhere to a crucial principle: adapt the process to the tea. Here are a few simple examples.

First, let's consider the handling of rain tea, which appeared frequently last spring. Fresh leaves picked early in the morning typically have a moisture content of about 20%, while those picked during rainy weather can have a moisture content of up to 40%. Therefore, a higher heat level is required during kill-green to ensure normal evaporation of the leaf moisture.

Thus, to avoid sticking and ensure successful kill-green, rain-soaked leaves should undergo extended withering to promote dehydration; the pan temperature should be increased, and the amount of leaves added should be reduced to maintain sufficient heat. For example, for every 5% increase in the moisture content of 100 pounds of fresh leaves, an additional 2% to 3% heat is needed during kill-green.

Second, there is the commonly mentioned “kill young” and “kill old” in the context of kill-green. When the leaf temperature is the same, the length of time for kill-green varies. Shorter times mean less moisture is evaporated from the fresh leaves, referred to as “kill young,” while longer times are “kill old.”

Typically, young leaves have a higher water content, stronger enzyme activity, and greater toughness, making them more prone to sticking together. Killing them “old” is beneficial for shaping. Older leaves have lower water content and weaker enzyme activity, and killing them “young” reduces the risk of producing broken tea leaves, which is also beneficial for shaping.

Finally, there are the common temperature and humidity control techniques of “suffocating kill” and “ventilating kill.” Covering the pan to retain steam and heat is called “suffocating kill”; uncovering and shaking the leaves to lower the temperature and reduce steam is “ventilating kill.”

In Pu'er tea kill-green, there is a technique called “ventilate, suffocate, ventilate,” meaning to ventilate for about two minutes, wait for the leaves to be evenly heated, then suffocate for about one minute once the leaf temperature rises. As soon as steam rises from the pan, immediately uncover and ventilate. This technique stabilizes the leaf temperature and avoids “smoky burnt tea” and