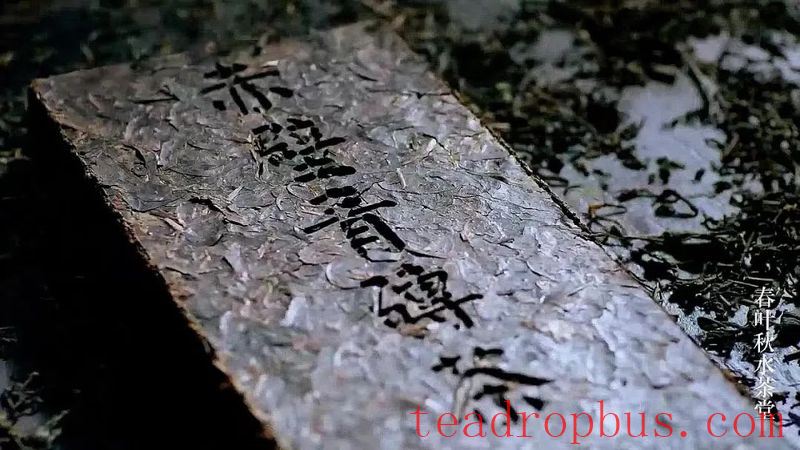

In regions like Inner Mongolia, people prefer to use Qing brick tea for making Milk tea. The tea has a dark green-brown color, is shaped like a brick, has a pure aroma, and a mellow taste. When brewed, it produces an orange-red infusion and its leaves turn dark brown. It belongs to the category of dark teas. Its main production area is in the Xianing region of Hubei Province, including counties such as Pochi (now Chibi), Xianning, Tongshan, Chongyang, and Tongcheng. As it was first produced in Yangludong, it is also known as “Dong Brick.”

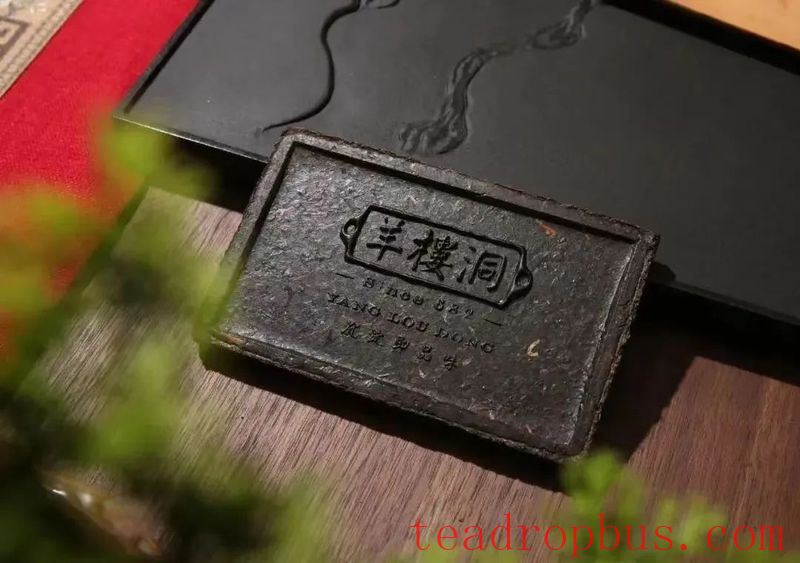

According to the “Hubei General Gazetteer,” in 1871 during the reign of Emperor Tongzhi, a revised regulation for tax collection on Black Tea and old tea was established for the six counties of Chongyang, Jiashan, Pochi, Xianning, Chengcheng, and Shancheng. The term “old tea” referred to here is Lao Qing tea, which has been produced for over 100 years. Around 1890, fried and basket-packed tea began to be produced in Yangludong, Pochi (now Chichi City). This involved frying the tea dry, breaking it into pieces, and packing it in bamboo baskets for transport to the north, known as fried basket tea. About ten years later, Shanxi tea merchants set up businesses in Yangludong, using Lao Qing tea as raw material for steaming and pressing to experiment with producing Qing brick tea. Because the surface of the pressed bricks had the trademark “Chuan,” it was also called “Chuan” tea.

Some curious friends may ask, why do these tea bricks have the character “Chuan”? After all, Qing brick tea is produced in Hubei Province, mainly sold to Mongolia and Russia in the north, not in Sichuan. In fact, this character “Chuan” is primarily related to the tea houses and merchants who operated the Qing brick tea business. The earliest merchant in Yangludong associated with “Chuan” was the largest Mongolian trading company from Shanxi, “Dashenggui,” which operated the “Dayuchuan” tea house (later renamed San Yuchuan).

According to the Inner Mongolian historical records in “Traveling Mongolian Merchants Dashenggui,” the famous traveling Mongolian merchant Dashenggui invested in the “San Yuchuan” tea house, which was based in Yangludong, Pochi County, Hubei Province. The name “Dayuchuan” originated from a set of tea ware made in honor of the tea sage Lu Tong, called “Mr. Dayuchuan.” Lu Tong, who wrote “The Song of Seven Bowls of Tea,” styled himself as Yuchuanzi. Additionally, the “Chuan”-related businesses were also associated with the Qu family from Qixian, Shanxi.

The founder of the Qu family's business, whose given name was Bai Chuan, after arduous efforts, gradually became wealthy. Most of the tea houses operated by the Qu family in Yangludong were related to “Chuan,” such as “Changyuanchuan,” “Changshengchuan,” “Sanjinchuan,” and “Hongyuanchuan.” The words “Nachuang” hung on the gate tower of the Qu family mansion not only symbolized the meaning of embracing all rivers and accumulating wealth but also embodied the concept of “tolerance,” a lesson passed down by the entrepreneurial ancestors to their descendants.

From the 1870s to the 1880s, in the town of Yangludong, now part of Chibi City, which is less than one square kilometer in size, there were over 200 tea houses and tea processing workshops gathered together. It was truly an international tea trade town. In 2012, Yangludong was designated by the State Administration of Cultural Heritage as one of the sources of the Ten Thousand Li Tea Road, the hometown of Qing brick tea. As an important supply and processing center for tea in modern China, Qing brick tea started from here, traveling along the Ten Thousand Li Tea Road to reach the world, promoting the development of the two major tea markets in Hankou and Jiujiang.

Speaking of the production techniques, Qing brick tea is divided into three parts: top dressing, second dressing, and inner tea.

The top dressing is finer, while the inner tea is coarser. First-grade top dressing tea consists mainly of green stems, with a slight amount of red stems at the base, tightly twisted, slightly white-stemmed, and dark green in color. Second-grade second dressing tea consists mainly of red stems, with a slight amount of green stems at the tip, the leaves are in strips, and the leaf color is dark green with a hint of yellow. Third-grade inner tea consists of red stems from the current year without any old stems from the previous year. The process of making the top dressing includes seven steps: killing, initial kneading, initial drying, re-frying, re-kneading, piling, and drying. The process of making the inner tea includes four steps: killing, kneading, piling, and drying. Fresh leaves are processed into rough tea first, and then the rough tea undergoes sifting, pressing, drying, and packaging to produce the final product of Qing brick tea.

The fermentation degree of Qing brick tea is lighter compared to other dark teas. When drinking, first pry off a piece with a tea knife and Rinse it with boiling water. Rinsing the tea facilitates the subsequent release of flavor and aroma. Qing brick tea has a neat and smooth appearance, uniform thickness, a dark green-brown color on the brick surface, a bright orange-yellow infusion, and a special fragrance unique to Qing brick tea. When drinking, there is no greenish or astringent taste, and the leaves are coarse and dark brown when fully infused.

With the development of the times, advances in science and technology, and the acceleration of life rhythms, the traditional advantages of Qing brick tea for transportation and storage have been weakened, while the inconvenience of brewing has been somewhat magnified, affecting market expansion. To solve this problem, tea merchants have actively adapted to changes in the market, launching small-packaged tea products that are easier to Brew, allowing a broader range of consumers to enjoy the fragrance and experience the unique charm of Qing brick tea. We believe that in the future, Qing brick tea will certainly achieve greater development.