India's tea production surges while industry rival, Kenya, experiences a shocking slip in numbers.

India’s tea gardens are buzzing this year. From the plains of Assam to the misty slopes of Darjeeling and the Nilgiris, bushes are heavy with leaves. The warehouses are full, the auctions busy. Yet behind the bustle, the numbers reveal a far trickier picture — one of plenty in the fields but pressure in the markets.

A Season of Plenty

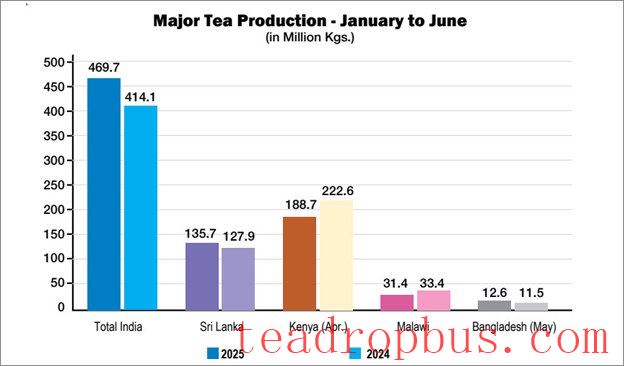

Between January and June 2025, India harvested 469.7 million kilos of tea, a 13% jump over the same period last year. North India, home to Assam and Darjeeling, produced 352.8 million kilos, while South India, led by Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Karnataka, contributed 116.9 million kilos.

Assam led the charge with close to 200 million kilos in the first half of the year, reinforcing its role as the backbone of Indian tea. West Bengal’s Terai and Dooars bounced back strongly, cushioning a minor dip in Darjeeling. Production in Darjeeling remained modest at 1.9 million kilos, but its reputation as the “champagne of teas” kept it valuable in global markets.

Internationally, India’s surge contrasts with mixed fortunes elsewhere. Sri Lanka gained around 8 million kilos, Bangladesh, too, showed an uptick, but Kenya — a heavyweight in exports — slipped by nearly 34 million kilos, tilting global supply lines in India’s favor.

The Price Puzzle

But in the auction halls, optimism is harder to find. North Indian auctions in July averaged ₹229 ($2.62) a Kilo, well below last year’s ₹258–300 ($2.63–3.44) range. South India, too, saw prices dip even as volumes rose.

Different categories tell different stories. Cut-Tear-Curl (CTC) teas, the workhorse of India’s domestic market, are weighed down by oversupply. Orthodox teas, however, continue to shine, often fetching more than ₹300 ($3.44) per kilo in auctions. Darjeeling remains untouchable, with July averages soaring past ₹570 ($6.53) per kilo.

“Good liquoring teas are expected to hold their ground despite higher overall production this year,” said a senior tea industry professional. “In contrast, medium and plainer grades will face pressure, with demand settling at lower price points due to their abundant availability.” As the season enters its busiest months, he warned of a “price concertina” effect, stating: “During this period, the divide between premium teas and the rest will become especially pronounced.”

Global Ripples

For international buyers, India’s expanded crop is a relief at a time when Kenyan exports are shrinking. Still, producers worry that higher availability will not automatically translate into higher earnings.

With Sri Lanka yet to reach its pre-crisis strength, Indian orthodox teas are finding more space in the Middle East, Russia, and Europe. Buyers short on Darjeeling are shifting toward Assam orthodox and Nilgiri whole-leaf teas.

Planters’ Dilemma

Back in Assam and West Bengal, the mood is cautious. Labor, fertilizer, and energy costs are rising sharply, eroding margins. Small growers, who contribute nearly half of Assam’s production, are feeling the squeeze the most.

“The Indian tea industry in 2025 stands at a critical crossroads, grappling with production fluctuations, falling auction prices, and an influx of imports that are straining domestic realizations,” the Indian Tea Association (ITC) warned in a statement.

Climate stress is making matters worse. “A 2°C rise in average day temperatures and reduced rainfall in June created dry conditions that stressed tea growth,” ITC noted. “This led to a 20–25% production drop in key tea-growing regions of Assam and West Bengal, while July output is projected to fall 15–20% compared to last year.”

A consultant from Assam described the sector’s predicament as the 4C challenge: “The tea industry in India — particularly in Assam — stands at a crossroads, caught in what growers call the 4C challenge: Climate, Compliance, Cost, and Capability. Of these, only one — Capability — is within the industry’s control. And it is here that technology offers a fighting chance.”

“The tea industry of North India is presently passing through turbulent times,” said Bidyananda Barkakoty, adviser, North Eastern Tea Association. He pointed out that the average price realization at the Guwahati Tea Auction Centre up to August 14 was lower by ₹25 ($0.40) per kilo compared to last year, while unsold teas climbed to 35% from 24% a year ago. Imports, too, have surged, rising to over 50 million kilos in 2024–25 compared to about 30 million kilos in 2022–23, mainly from Kenya and Nepal.

On the production side, Assam’s output up to June was 5% higher than last year, with all-India production up 13%. By mid-August, production was nearly at par with 2024. Barkakoty’s warning was blunt: “If tea prices do not rise in September, all tea estates and many factories will face a heavy cash crunch.”

The Road Ahead

Plenty of tea in the fields, plenty of worries in the markets — that is the paradox of 2025. Whether this year proves a blessing or a burden for India’s planters may depend on how prices move in the coming months, and how quickly the industry can harness the capability to withstand the blows of climate, compliance, and cost.