Pu'er Tea has a unique phenomenon: the market customarily refers to Pu'er teas produced in earlier years and still preserved as “aged tea.” Representative examples include “badge-level tea” and “print-level tea.”

An interesting phenomenon is that these teas are not referred to as “aged tea,” but instead are given the title of “aged tea,” which not only extends the shelf life of Pu'er tea indefinitely, but also implies a higher quality.

In essence, “aged tea” has become synonymous with the highest quality or the pinnacle of tea tasting.

The emergence of the concept of “aged tea” is actually related to the “post-fermentation” of Pu'er tea. Since Pu'er tea's post-fermentation process possesses the “ripening action” function in tea storage chemistry, it has the characteristic of becoming more fragrant over time. The term “aged” represents maturity, naturally forming the representative of the highest quality of Pu'er tea.

This article attempts to find several key points of the biological characteristics of “aged tea” through qualitative and quantitative analysis of certain specific physicochemical indicators based on sensory evaluation.

Preparation method: Steep ten grams of “aged tea” (dry leaves) with boiling water, then combine the fourth and fifth infusions and pour them into a round glass pitcher. Evaluate from the aspects of color, aroma, taste, and appearance.

Color of the tea infusion: A gemstone red hue

Gemstone red can be further divided into redness, brightness, and deep red (dark red). This is an initial sensory evaluation. Additionally, two auxiliary conditions are needed: one is to observe under natural light and spotlight conditions using a frontal view, presenting clarity and brightness; the second is to observe from above, where the reflection point at the bottom of the cup (a golden yellow dot) can be seen. Chemical analysis reveals:

①Theaflavins account for 1% to 2% of the solid matter and are the primary substances that make the tea infusion of “aged tea” appear bright.

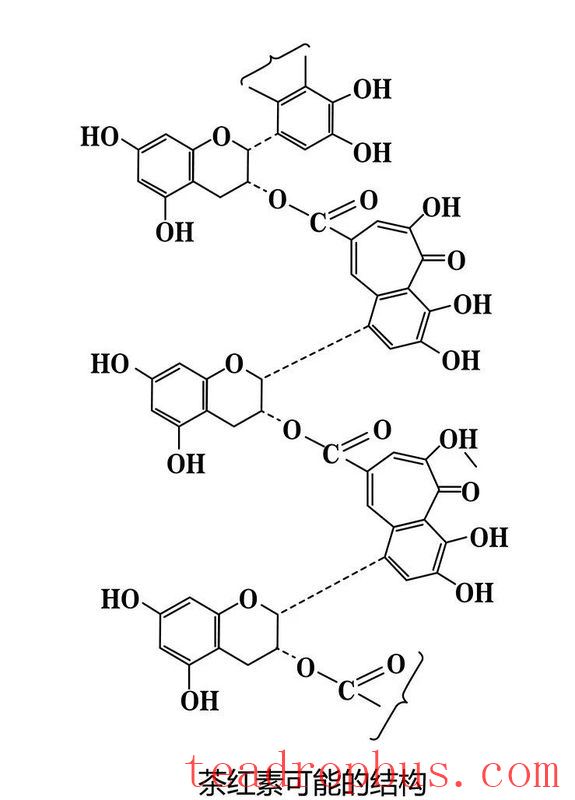

②Tearubigins are the dominant substances that give “aged tea” its redness, accounting for 10% to 15% of the solid matter. They are the main pigments in “aged tea” and are unique to “aged tea,” being very precious fermentation products. These tearubigins, accurately speaking, are tearubigin groups, derived from a class of complex heterophenolic pigment substances. They are complex brownish-red phenolic compounds. Therefore, they contain the non-enzymatic reaction products of catechin oxidation products, polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids, and proanthocyanidins, as well as enzymatic oxidation and polymerization products of tea polyphenols. (Illustration: Chemical structure of the tearubigin group)

③Theabrownins account for 4% to 9% of the solid matter and are the main substances that give “aged tea” its dark red and heavy appearance.

Possible structure of tearubigins

When theaflavins, tearubigins, and theabrownins intermix in moderate proportions, they collectively create the unique “gemstone red” color of Pu'er tea. This “gemstone red” is naturally produced during the post-fermentation process and, more accurately, is the exclusive pigment system of “aged tea,” serving as its signature substance.

Aroma: A faint scent of agarwood and wood

Raw Pu'er tea contains aromas such as camphor, orchid, honey, and lotus leaf, while ripe Pu'er tea has jujube and caramel aromas, among others. There are over a hundred aroma substances. However, after post-fermentation lasting over thirty years, many of these aroma substances have naturally volatilized and decreased. By the stage of “aged tea,” there are only twenty to thirty aroma substances remaining, mainly originating from linalool compounds. The scent of agarwood is the expression of the aroma of linalool in the linalool compounds, with a faint medicinal scent.

The wood scent comes from the aromatic substances produced by the interaction between linalool and yeast during post-fermentation.

The “ginseng aroma” found in many “aged teas” is the result of reverse use of the method employed in ancient China (mainly during the Ming and Qing dynasties) to prevent ginseng from molding by wrapping it in tea leaves (for reference, see the author's article “Where Does the Ginseng Aroma in Pu'er Tea Come From?” published in November 2016).

The study of aromatic substances in “aged tea” is the most complex. Because the cellular pores of large-leaf tea are relatively large, they have strong adsorption of external odors. Therefore, different storage methods and different external odors may penetrate the tea leaves. Many of the aroma types associated with “aged tea” circulating in the market do not originate from Pu'er tea itself but are due to the intrusion of external odors.

The aromatic substances in Pu'er tea follow only one path: microorganisms produce large amounts of enzymes when acting on Pu'er tea. These enzymes serve as “catalysts” in the fermentation process of Pu'er tea, degrading and converting large quantities of phenolic substances. Among the converted substances are small amounts of alcohol compounds, which further convert the small quantities of lipids in the tea leaves into various aromatic substances. These aromatic substances are present in very low concentrations, almost at the level of one or two parts per ten thousand, and their aromas are extremely weak, at about one or two percent of the level of new tea.

These substances almost all come from linalool in the tea leaves, hence the faint scents of agarwood and wood, which are the primary aromas of “aged tea.”

Taste: Rich and smooth, the taste of no taste

During long-term post-fermentation, the content of tea polyphenols in Pu'er tea decreases from the initial 25% to 32% to between 5% and 9%. Large quantities of lipid-soluble substances in the tea leaves are converted into water-soluble substances (natural plant biotransformation), giving rise to many small molecule compounds, creating the feature of “aged tea” having a higher content of water-soluble substances than new tea. Because there are more water-soluble substances, the “density” of the tea infusion is naturally higher, giving the impression of being “rich”; simultaneously, the vast majority of substances in the tea infusion are small molecules (products of fermentation) that easily blend with water, forming the concept of a “juice,” leaving an impression of “smoothness” upon entering the mouth. Thus, the terms “rich” and “smooth” are commonly used in popular descriptions.

In addition to “rich” and “smooth,” “aged tea” also has the saying of “the taste of no taste.” This phrase first appeared during the Qianlong era of the Qing dynasty, when Qianlong gave this evaluation after tasting Longjing tea in Zhejiang, roughly meaning: At first sip, Longjing tea seems tasteless, but upon further sipping and savoring, one perceives a gentle sweetness. He thus remarked that the taste of no taste is the supreme taste. Nowadays, Longjing tea no longer uses this description, having changed its clientele, and it now applies to “aged tea.”

In fact, describing “aged tea” as “the taste of no taste” is accurate, because after long-term storage, “aged tea” should not have a strong aroma or a “hard” flavor (like the intensity of new tea), but rather a gentle and elegant sweetness. At the same time, this “gentleness” is not the tastelessness of “plain water,” but rather a rare and even indescribable individual experience. Only analogous exaggerated artistic words can be used to summarize it, aiming to convey the meaning of “supreme taste.” Clearly, this phrase is highly emotional.

Shape of the infused leaves: A special cicada wing-like shape

The infused leaves of “aged tea” are dark brown, with a slight luster appearing after immersion in boiling water. However, this alone is difficult to distinguish. Here is a little trick: spread out the leaves and observe them against a well