“Brewing tea” and “boiling tea” are common tea drinking methods today, but what is “Diancha”? What is the relationship between “Diancha” and the long-lost traditional skill “Chabaixi”?

Today, let's clarify the differences between “Diancha, Doucha, and Chabaixi”.

Diancha

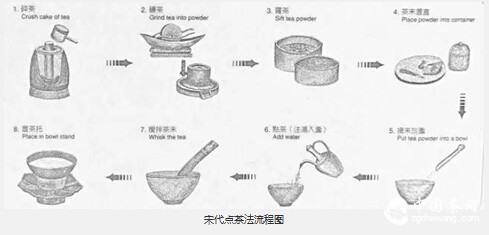

In the Song Dynasty, tea was still consumed from compressed cakes, but most were no longer boiled directly. This method was called Diancha. For Diancha, finely ground tea powder was placed directly into the tea bowl, then boiling water was poured over it, stirred slightly, and then drunk.

Before Diancha, the cup was rinsed with boiling water to preheat the vessel, ensuring the “cup stays hot so the tea cools slowly, preserving its flavor”. Tea powder was placed in the cup, and the best water from a suitable pot was used to pour directly and forcefully into it, without interruption. Then, “mixing the paste” involved adding a specific amount of tea powder to the cup based on its size, injecting boiling water, and mixing it into a thick, oily paste. Finally, a tea whisk was used to whip and froth the mixture, completing the tea soup.

Doucha

Building upon the Diancha method, Song people created an entertainment form known as “Doucha”.

“Doucha,” also called “Tea Battle,” was a competition comparing the quality of tea and the skill of preparing Diancha. The trend of Doucha began in the Five Dynasties period and became extremely popular in the Song Dynasty,热衷于此 from scholars and officials to common people. Su Dongpo once recorded the prevalence of “Doucha” in the Huizhou area of Lingnan: “Outside the mountains, only the Huizhou custom enjoys Doucha.”

Doucha initially aimed to judge tea quality but later became widely popular as a folk game. Before Doucha, tea leaves were crushed and sifted; the finer the powder, the better, as it would float easily in water and produce abundant, gathering foam, thus “fully displaying the tea's color.”

Lavish court Doucha emphasized “foam” and “color.” The ideal color for the whipped tea was pure white, with bluish-white being secondary. It also required the tea powder to be finely ground and sifted.

Folk Doucha, focusing on the intrinsic quality of tea, emphasized the tea's “aroma” and “taste,” valuing the evaluation of fragrance and flavor over whether the tea soup was white or green.

The outcome of Doucha primarily depended on the color and evenness of the tea foam, and the “water mark” where the tea soup met the cup. Uniform, bright white foam was considered superior. Foam that clung tightly to the cup walls for a long time without dispersing was highly valued, called “biting the cup” (Yaozhan), while foam that scattered quickly was termed “disorderly cloud feet” (Yunjiao Huanluan).

Fencha (Chabaixi)

Fencha emerged as Diancha skills advanced. Fencha, also called Chabaixi, Water Ink Painting, Soup Play, or Tea Play, is an ancient tea way where patterns and images are formed by the veins and textures in the tea froth. It not only created rich foam but also formed characters and pictures within the tea soup, enhancing the artistry and entertainment of Diancha and further boosting the popularity of Doucha.

This art form roughly began in the Tang Dynasty. Without modern records, we glimpse its spectacle through literature.

Tang poet Liu Yuxi described in his poem: “The sound of sudden rain enters the tripod; white clouds fill the bowl, flowers linger.” depicting the nascent form of patterns appearing in the tea soup.

In the Song Dynasty, favored by the court and literati, Fencha flourished. Tao Gu of the Northern Song recorded in “Chuanming Lu” an entertainment called “Chabaixi”: “Tea became popular in the Tang. Recently, some, using the spoon in the soup with special skill, can make the soup's lines and veins form images—birds, beasts, insects, fish, flowers, and plants—as delicate as paintings. But they scatter and vanish in a moment. This is the transformation of tea, called Chabaixi by contemporaries.” The “Chabaixi” Tao Gu described is what later became known as Fencha; the method was the same.

Many literati enjoyed “Chabaixi,” including the famous poet Li Qingzhao, who wrote lines like “Raw fragrance scents the sleeves, the lively fire divides the tea,” and “Cardamom stems boiled together in water, do not divide the tea.” Emperor Huizong of Song, Zhao Ji, was also skilled in Fencha. Thus, during the Song, from emperors to scholars, monks, and even street vendors, many could perform Fencha.

After the Yuan Dynasty, the elegant Diancha way and the art of Fencha declined. Traces persisted into the Ming and Qing dynasties. According to Qing poet Gao E's “Tea”: “An earthen pot boils spring snow, a light fragrance arises from ancient porcelain. After dividing the froth by the sunny window, comes a guest on a cold night.” By the late Qing, no detailed records of Fencha practice remain; this exquisite tea art had been lost.

In summary, “Chabaixi” is a tea art technique that酝酿ed in the late Tang and Five Dynasties, formed in the early Northern Song,流行ed during the two Song dynasties, declined in the Yuan, and was lost by the late Qing period.