Water is the mother of Tea, and ware is its father.

Tea ware comes into being because of tea, and it is made beautiful by tea.

In the Tang dynasty, tea was boiled; in the Song dynasty, it was whisked; and from the Ming to the Qing dynasties, it was steeped.

Throughout history, different drinking methods have led to various uses of tea ware.

Over a thousand years, each era has had its own tea-drinking fashion, and tea ware serves as the carrier of these fashions.

Today is International Museum Day, so let's explore the trendiest tea ware across the dynasties and feel the charm that spans a thousand years!

Seizing the Verdant Peaks

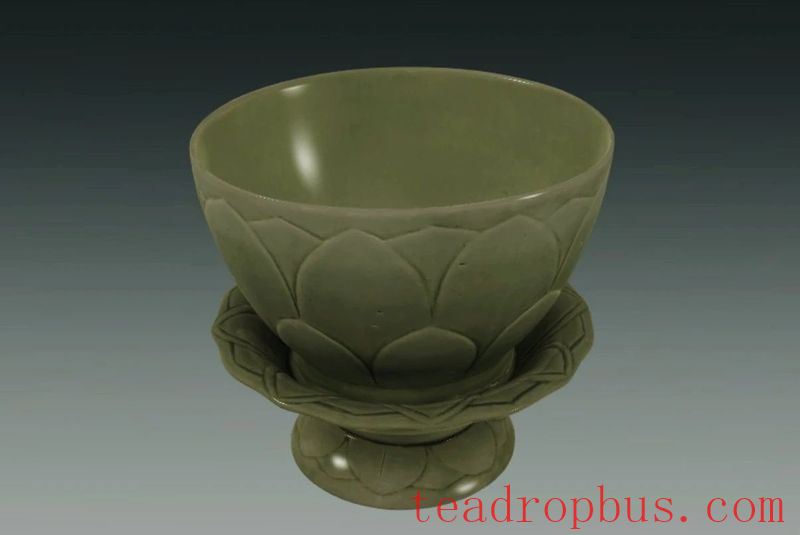

Tang Dynasty Yue Kiln Celadon Tea Bowl

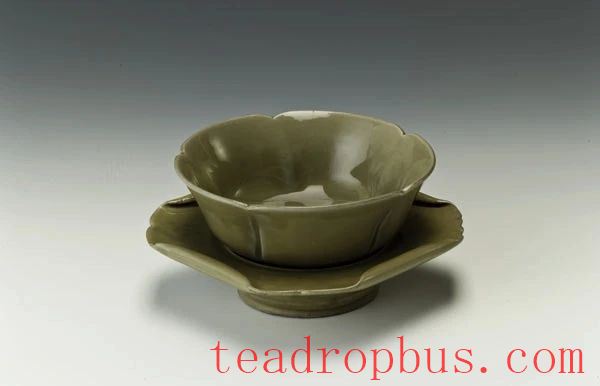

Tang Dynasty Yue Kiln Celadon Lotus Leaf Tea Cup with Saucer

Ningbo Museum Collection

Excavated in 1975 from the Heye Road Dock Site in Ningbo City, this set consists of a tea cup and saucer. The body is finely textured, and the glaze is a vibrant green, glistening like dew. The tea cup is shaped like an open five-curved lotus flower, while the saucer's edges are slightly curled, resembling a leaf supporting a blooming lotus on a tranquil water surface, swaying in the breeze.

When Chinese people first started drinking tea, they did not have dedicated tea ware. Bowls for food, cups for soup or wine could all be used for tea. Even the name for tea was not standardized, with terms like “jiǎ,” “shè,” “míng,” and “chuàn” all referring to tea. Lu Yu was the one who ended this chaotic situation and became the founder of Chinese tea aestheticism.

Lu Yu favored Yue ware, which was mainly produced in the region around Yue Prefecture (present-day Ningbo and Shaoxing areas in Zhejiang Province). He believed Yue ware surpassed Xing ware for three reasons: “Xing ware is like Silver, while Yue ware is like jade; Xing ware is like snow, while Yue ware is like ice; Xing ware is white and makes the tea color red, while Yue ware is green and enhances the greenness of the tea.” (The Classic of Tea – Chapter Four: Ware)

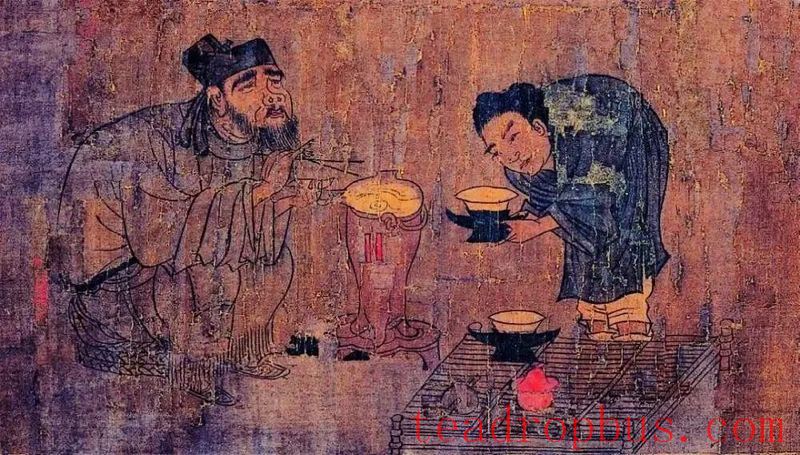

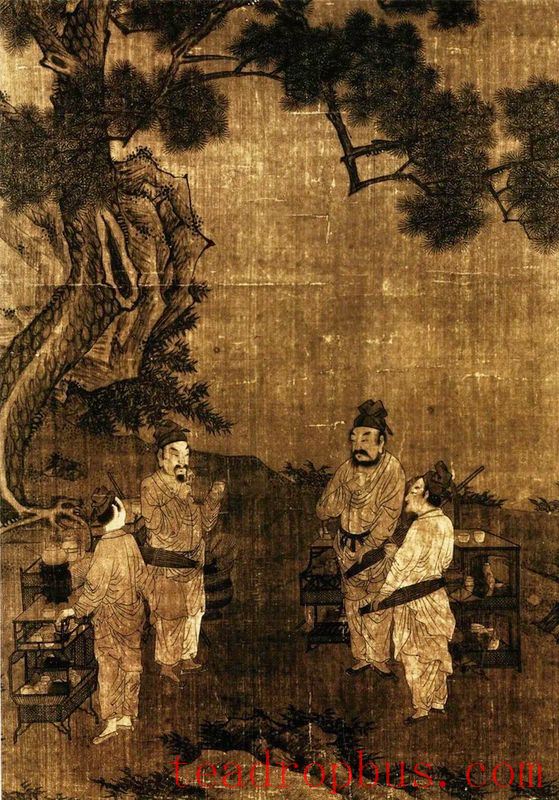

Tang Dynasty Yan Liben's “Xiao Yi Obtains the Preface to the Orchid Pavilion”

(Southern Song Dynasty replica, National Palace Museum, Taipei)

Without comparison, there would be no harm. He judged the quality of the ware based on whether its color enhanced the tea color: “Both Yue and Yue kilns produce celadon, which complements tea well.”

Shanglin Lake Yue Kiln National Archaeological Site Park

The Secret-Color Yue ware of the late Tang and Five Dynasties refreshed the technical and artistic heights of Yue kiln ceramics. “After nine autumn winds and dew, the Yue kiln opens, seizing the verdant peaks.” (Tang Dynasty Lu Jiumeng, Secret-Color Yue Ware) “Cleverly carved out of the moon and dyed with spring water, thinly spun ice holds green clouds.” (Tang Dynasty Xu Yin, Secret-Color Tea Cups Offered as Tribute). In the poets' words, Secret-Color ware is filled with the brightness and gentleness of Jiangnan landscapes.

Wuyue Dynasty Secret-Color Celadon Lotus Bowl (Suzhou Museum Collection)

Due to geographical proximity and cultural ties, Japanese envoys, monks, and students came to China in batches. With the eastward transmission of Chinese tea and Buddhism, celadon tea ware represented by Yue kiln profoundly influenced the formation of Tea culture in the Korean Peninsula and Japan.

Goryeo Celadon Five-Petal Flower-Shaped Saucer (circa 12th century)

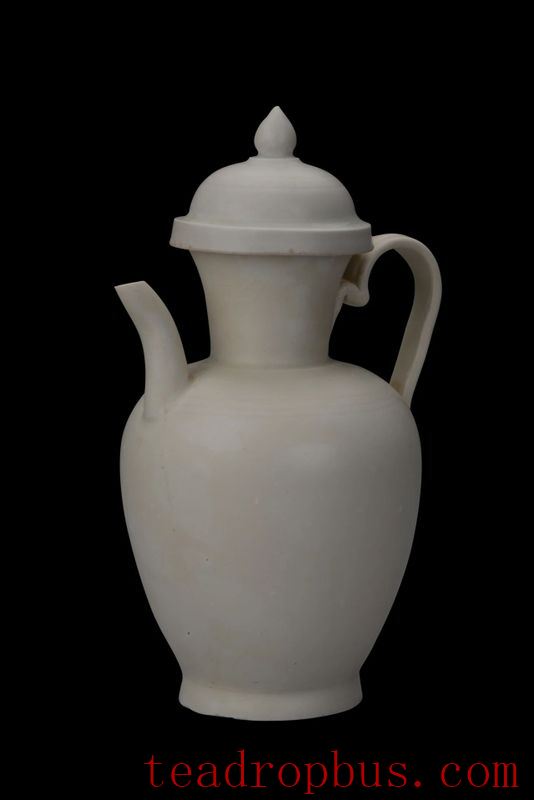

However, we cannot overlook the status of Xing ware in Tang Dynasty tea ware. “The craftsmen from Xing and Yue both make such vessels. They are round like fallen moon spirits, light like rising cloud souls.” (Tang Dynasty Pi Rixiu, Miscellaneous Verses on Tea – Tea Cups). Yue and Xing wares, “green in the south and white in the north,” shared equal prestige.

Tang Dynasty Xing Kiln White Glazed Jug (Zhengzhou Elephant Ceramic Museum Collection)

R. MUSEUM

Rabbit-Hair Patterned Cups Brew Cloud Liquid

Song Dynasty Jian Kiln Black-Glazed Tea Cup

Song Dynasty Jian Kiln Black-Glazed Rabbit-Hair Patterned Cup

National Museum of China Collection

The body is iron black, glazed inside and unglazed at the bottom outside. The glaze is thicker at the lower abdomen, and white streaks appear, commonly known as “rabbit-hair patterns.” These patterns are loved for the yellow or white hair-like lines formed by crystallization in the glaze.

Jian cups, also known as “Black Jian” or “Black Mud Jian,” were the mainstream tea ware for whisking and competing tea during the Song Dynasty, both in terms of functional design and aesthetic appeal.

“White tea looks best in black cups.” During the Tang Dynasty, green tea was favored, hence Lu Yu recommended Yue kiln celadon tea bowls that resembled ice and jade. In the Song Dynasty, white tea was valued, like snow or willow fluff. Using black to contrast white is the most direct and visually impactful way to present whiteness.

The glaze colors include dark blue-black, rabbit-hair, oil-drop, iridescent, and variegated, with “dark blue-black” (referred to as “qinghei” by Emperor Huizong Zhao Ji) being the most revered.

Emperor Huizong Zhao Ji preferred black cups with rabbit-hair patterns for whisking tea: “The color of the cup should be dark blue-black, with clear and distinct rabbit-hair stripes as the best, as it enhances the color of the tea.”

Song Dynasty white tea is perfectly complemented by the black Jian kiln cups.

Song Dynasty Liu Songnian's “Tea Competition” (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

In addition to Jian kiln, the wood-leaf Tenmoku cups from Jizhou kiln in Jiangxi Province were also highly regarded in Japan. Hebei Ding kiln and Cizhou kiln also produced black