China is the birthplace of Tea and the first country in the world to discover and utilize tea leaves. Tea is also one of our main local specialties and traditional export goods. Chinese Tea is renowned worldwide for its long history, wide variety, and high quality. The ancient Bashu region was among the earliest places in China for Tea drinking and cultivation, making it one of the cradles of the tea industry in the country. Today, almost every county and city in Sichuan Province produces tea, each with its unique advantages. The province ranks highly among tea-producing provinces in terms of both annual production and exports, contributing significantly to enriching people's lives and generating foreign exchange earnings.

The ancient Bashu region covered a vast territory, including present-day Sichuan, Yunnan, Guizhou, as well as parts of western Hunan, western Hubei, and southern Shaanxi. According to current tea-producing regions in China, this area falls within the Southwest Tea Region, one of the four major tea regions in the country. As previously mentioned, this region is the origin or peripheral area of tea trees and has had tea trees distributed throughout since ancient times.

The History of Huayang State, written by Chang Xu, a historian from Jiangyuan (present-day Chongzhou City, Sichuan Province) during the Eastern Jin Dynasty in 347 AD, is an invaluable local chronicle. In the chapter titled History of Ba, it mentions that some ethnic minority tribes in the Bashu region followed King Wu of Zhou in his campaign against the Shang Dynasty, and the local products, including “…cinnabar, lacquer, tea, honey… were all offered as tributes.” The same book, in the chapter History of Shu, records: “The king of Shu separately enfeoffed his younger brother Jiameng in Hanzhong, with the title of Marquis Jia, and named his domain Jiameng.” Yang Shen's Examination of Prefectures and Barbarian Lands states: “Jiameng, according to the Records of Han, is the name of a prefecture in Shu, pronounced ‘mang.' According to Dialects, the people of Shu called tea ‘jiameng,' hence the name of the prefecture derived from tea.” According to annotations in the Ciyuan (Dictionary), the ancient Jiameng Prefecture was located fifty li southeast of today's Zhaohua County, Sichuan Province. Naming a prefecture after an alternative name for tea indicates that there was a substantial amount of tea produced locally. The History of Shu also lists “Shifang (today's Shifang City) mountains produce good tea,” and “Nan'an (today's Leshan City) and Wuyang (today's Pengshan County) all produce famous teas.” These areas were under the rule of the King of Ancient Shu, King Kaiming, which corresponds to the Warring States period. Therefore, it can be seen that the tea-producing regions in Bashu were already quite extensive before the Qin Dynasty.

So why are there no records of tea in pre-Qin works? It is widely known that before the Qin Dynasty, the cultural and economic center of the country was in the Yellow River basin. Bashu was geographically isolated and culturally lagging, lacking written records about tea. Additionally, the towering mountains cut off its interactions with the Central Plains, so the knowledge of tea drinking and cultivation in Bashu did not reach the north at that time. Since the year 316 AD when “Qin attacked Shu and destroyed it” (as recorded in the Chronological Tables of Six Dynasties in the Records of the Grand Historian), the “gateway” to Bashu was opened. Later, General Sima Cuo of Qin led troops from Shu downstream along the Yangtze River to conquer the south, and Emperor Liu Bang of Han relied on the human and material resources of Shu to defeat Xiang Yu and unify the country. During these large-scale wars involving massive migrations, the economic and cultural exchanges between Bashu and other regions in the south and north were promoted, and the spread of tea from Bashu to other regions was facilitated. From this perspective, Gu Yanwu's statement in Records of Daily Knowledge that “only after the Qin conquered Shu did people start to know about tea drinking” aligns with historical facts.

After the unification of China by the Qin Dynasty, Wen Weng, the governor of Shu Commandery, promoted education, while Li Bing developed water conservancy projects, leading to rapid development of culture and agriculture (including tea) in the Western Sichuan Plain. By the Western Han Dynasty, numerous scholars and writers emerged in Shu, and their writings began to include records related to tea.

During the reign of Emperor Wu of Han, Sima Xiangru, a famous writer from Chengdu, recorded nineteen medicinal plants in his work General Will Chapter, among which “chuancha” was an alternative name for tea. At the end of the Western Han Dynasty, another writer from Chengdu, Yang Xiong, wrote in his Dialects: “In the southwest of Shu, tea is called jia” (both texts are cited in the Treatise on Tea). Yang Xiong's Capital of Shu Fu also contains the lines: “A hundred flowers bloom in spring, faintly fragrant, tea and reeds flourish, green, purple, and yellow.”

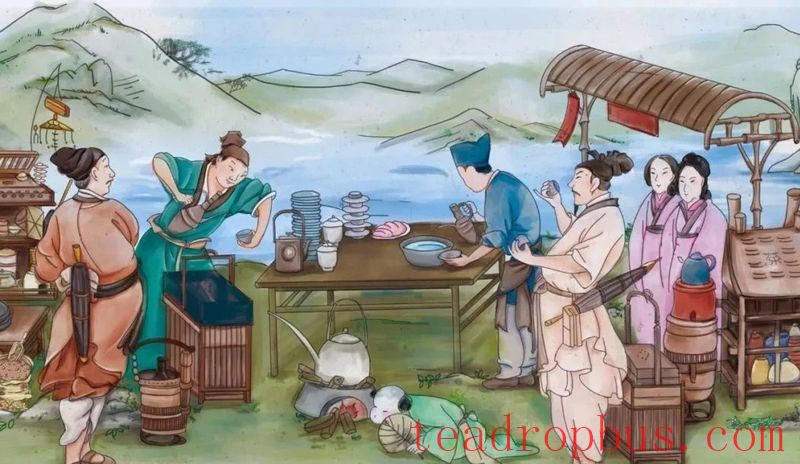

A particularly important document for tea historians is Wang Bao's Tongyue from the third year of the Shenque era (59 BC) during the reign of Emperor Xuan of the Western Han Dynasty. Wang Bao was from Zi County (now part of Ziyang City) in Shu Commandery and held the position of Counselor. Tongyue is a contract he wrote when purchasing a servant, specifying various tasks the servant should perform, including “prepare tea utensils” and “buy tea in Wuyang.” The ancient city of Wuyang is now Shuangjiang Town in Pengshan County, not far from Chengdu, with convenient land and water transportation, and is a place mentioned in the History of Huayang State as producing famous tea. This proves that the gentry class in the Western Han Dynasty had the habit of Drinking Tea in their daily lives, and tea had become a commodity traded in the market.

By the Han Dynasty, the tea varieties and cultivation methods of Bashu had spread to the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. The county of Chaling in Hunan Province, founded in the early Western Han Dynasty, was named after its tea production. According to anecdotal historical sources, the Immortal Old Man's Tea Garden on Mount Gaizhu in Zhejiang was planted by Ge Xuan, a famous scholar of the Han Dynasty.

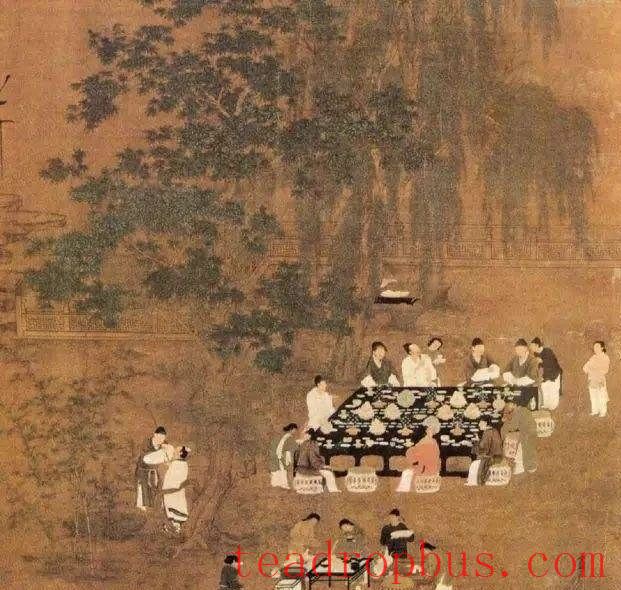

During the Jin Dynasty and the Southern and Northern Dynasties, tea production gradually increased in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River and extended into the Huai River basin. During the reign of Emperor Yuan of the Eastern Jin Dynasty, Minister Wen Qiao, who was stationed in Xuancheng, submitted a memorial offering over a thousand catties of tea. During this period, northerners were accustomed to drinking sour gruel, while southerners generally preferred tea. Especially among the gentry, who avoided reality and valued clear discussions, sipping tea and composing poetry became popular, thus forming an enduring connection between tea and poetry. For example, the line “Fragrant tea surpasses the six clear elixirs, its taste spreads through nine regions” in the poem Ascending the White Rabbit Tower in Chengdu by Jin Dynasty poet Zhang Zai is a praise of Shu tea.

Zhang Ji's Broad Learning from the Northern Wei Dynasty records: “In Jing and Ba, they pick leaves and make them into cakes. When the leaves are old, they use rice paste to shape the cakes. To prepare tea for drinking, they first roast the cakes until red, grind them into powder, place them in porcelain ware, pour boiling water over them, and