Leaving Qizong Town at the southern end of Weixi, I continued to head north along the Jinsha River Gorge. The landscape was a stark contrast to the snow-capped highlands of the past two days. The valley carved by the river nurtured a different Tibetan land. After passing Jiangdong Village, the Xiangwei Highway turned east and began to ascend, gradually revealing the highlands once again as the mountains and river faded into the distance.

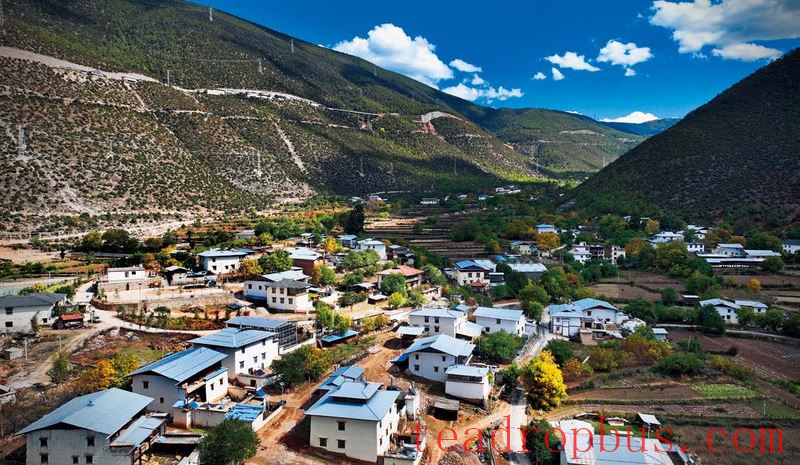

Twenty minutes later, following my navigation, I arrived in Tangdui. Unlike the icy winds hovering around the freezing point at Wunongding on the previous morning, Tangdui Village, nestled among the hills and scattered across the gentle slopes of the valley, had warm and soft air. Despite being nearly 3,000 meters above sea level, it enjoyed gentle sunshine that wasn't harsh and autumn breezes that were cool but not cold.

In early November, the city of Shangri-La already had a chill in the air during the early mornings and evenings, but thirty kilometers away, at the foot of Shika Snow Mountain, Tangdui was still warm and pleasant. The afternoon sun spread evenly over the valley, while a few children played and laughed in front of old trees and ancient houses, and yaks wandered leisurely through the village.

The prayer wheels beside the spinning prayer flags swayed with auspicious colors. The simple houses and rural fields were tranquil, occasionally interrupted by the sounds of roosters crowing and dogs barking. Everything was pure, just like what is depicted in Tao Yuanming's works, the scene that the wealthy urbanites, weary of worldly life, would spend their family fortunes to pursue. It was probably something akin to this.

I had imagined the ancient route where black Pottery was produced to be bustling and lively, but Tangdui was quiet everywhere. Upon inquiry, I learned that it was the farming season, and most villagers were working in the fields. Occasionally, some people took breaks from their work on the field edges, and if not for necessary tasks, they rarely made pottery during this season. My plan to visit Sunuo Qilin's Intangible Cultural Heritage workshop had to be abandoned.

On my way back to the village entrance, I met Anwon, who had returned from working in the fields. Seeing leaves blocking the water ditch, he put down his farming tools and started cleaning. After exchanging greetings, Anwon shouted a few words in Tibetan towards a nearby courtyard, then turned to me and said that his family was still making pottery, and I could go take a look. Entering the courtyard, the elderly man greeted me with a hand covered in clay, then continued with his work.

He said he was making a few earthen pots for some friends from Fujian. If I wanted to see the whole village engaged in pottery making, I could come back when spring flowers bloom next year. At that time, the sight of smoke rising from the kilns would surely be lively and vibrant. Of course, it had to be before the matsutake mushroom season, or else it would be another “empty city” scenario.

During my chat with the elderly man, the people and scattered tools, a beam of sunlight shining through the window, and the unfinished pottery by my side instantly evoked the flavor of folk craftsmen. The traces of time from the Tea Horse Road became visible.

In the past, Tangdui was a must-pass place on the Tea Horse Road, and handmade black pottery was sold throughout the Tibetan areas by horse caravans. The pottery-making tradition in the Nixi Tangdui area can be traced back to around 850 BC. With the development of history, the craftsmanship has become increasingly mature and perfected, forming a relatively stable production process that is still in use today. In Deqin, many families cannot do without a few black pottery hotpots and Teapots.

One can imagine that in winter along the Yunnan-Tibet line, with howling cold winds and flying snow outside, the stores are warm and cozy with blazing fires. The chicken soup in the earthenware pot is steaming hot, and crushed Longba peppers are added to the rich broth. Accompanied by stir-fried potatoes and Tibetan smoked pork, one eats until they sweat all over. Then, a pot of warm sweet tea is served, satisfying not only the taste buds but also the warmth of this world and the leisure of half a day.

Sitting under a wooden shed drying stalks and Sugar beets, I looked up the meaning of Tangdui. It is a transliteration of the Tibetan pronunciation, with “tang” meaning “valley” and “dui” meaning “high place.” However, this village, which isn't considered particularly high in the Hengduan Mountains, seems to be what Shangri-La looks like in “Lost Horizon.” To the north of the village lies the Xigui Holy Mountain, with fluttering prayer flags halfway up and nine white stupas built at the foot. The walnut tree beside the stupa is said to be a thousand years old, with lush branches and abundant fruit. This is the perfect season for them to ripen.

The footsteps of the ancient road have gradually faded into the distance, and today, Tangdui is peacefully stepping into the world.

Originally published in Pu'er Magazine