From the Ming dynasty to the early Qing Dynasty, Pu'er Tea was already born in the territory of Cheli Xuanweisi in the southwestern frontier, but the term “Six Great Tea Mountains” was not popular. Instead, the term “Tea Mountain” appeared more frequently, referring to an independent region in Xishuangbanna, or a separate tax unit under the jurisdiction of Cheli Xuanweisi.

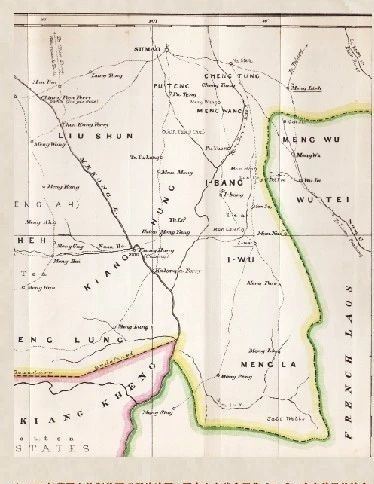

In 1661, Wu Sangui divided half of the Pu'er area to Cheli and the other half to Yuanjiang. He placed Pu'er, Simao, Puteng, Tea Mountain, Mengyang, Mengnuan, Mengpeng, Menglao, Mengxie, Mengwan, Mengwu, Wude, Zhengdong, and thirteen other regions under the jurisdiction of Yuanjiang Prefecture.

Three years later, each of the regions on both sides of the river returned to the jurisdiction of Cheli Xuanweisi.

In 1729, a Jiangxi tea merchant went to Mangzhi to purchase tea. At that time, the Tea Mountain was bustling with merchants from various provinces who came to buy tea for profit. Among them, Jiangxi merchants were known for their hard work and thrift. This Jiangxi merchant had a conflict with his host, Mabupeng, while purchasing tea and staying at his place. The “Yunnan Annual Historical Records” recorded it as follows: “Mangzhi (Tea Mountain) produces tea, and merchants often stay at tea farmers' houses when buying and selling tea. A Jiangxi guest committed adultery with Mabupeng's wife, which was exposed. Mabupeng killed the Jiangxi guest and cut off his hair as proof, showing it to the other merchants. The merchants then reported a robbery and murder, claiming that ‘it was instigated by Dao Zhengyan, the head of Oladamba.' Dao Zhengyan was well-known for his wealth, and it was said that he was involved in the robbery.”

Eertai heard that the local leader, Dao Zhengyan, “had called upon the Hani people to attack merchants and harm civilians,” and was starting a rebellion. Busy suppressing the rebellion in Wumeng (today Zhaotong), Eertai immediately ordered General Haoyulin to send troops to suppress the uprising. In Yibang, Youle, and areas within the river, the local ethnic minorities gathered to fight against the government troops. Due to the unfamiliarity with the terrain, the government troops suffered heavy losses multiple times. However, the disorganized rebels could not match the well-trained government troops. The following year, Mabupeng was captured, and Dao Zhengyan, the chief of Oladamba in Mengla Tea Mountain, was also caught and executed by Qiu Mingyang.

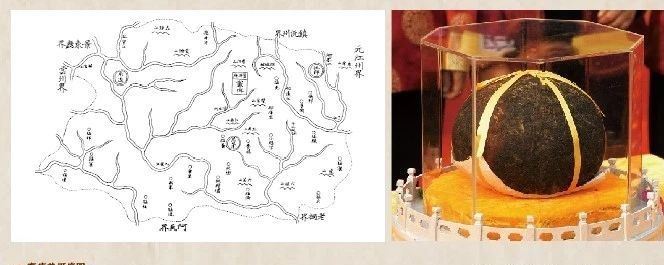

To permanently resolve the Tea Mountain issue and prevent those opposing the Qing government from using the Tea Mountain as a place to escape, the Tea Mountain was surrounded. People would enter to collect tea for a living and leave to raid for survival. Eertai suggested the implementation of the “replacement of native officials with imperial officials” policy in the Tea Mountain. This meant restricting the power of local leaders in the regions east of the Lancang River (within the river) and setting up officials appointed by the central government to oversee them. In the seventh year of Yongzheng (1729), Pu'er Prefecture was established, and a magistrate was placed in Simao. One military commander was stationed in each of Oladamba, Yibang, and Mengwu (now part of Laos) with troops. As a result, the Six Great Tea Mountains came fully under the control of the government troops. To avoid conflicts between tea merchants and local indigenous tea farmers, Eertai recommended to the Emperor: “The Tea Mountain is a strategic location in Cheli. Previously, unscrupulous tea merchants heavily indebted the people, monopolizing the mountains, leading to desperate resistance from the locals. It is estimated that the Six Tea Mountains produce around six to seven thousand loads of tea annually.”

This means that the total production of tea from the Six Tea Mountains (with each load being about 120 catties) amounted to between 7,000 to 8,000 piculs. This tea had to be transported to the main tea store in Simao for trading. All the power was centralized in the hands of the government, which reduced conflicts between merchants and the indigenous population to some extent but also fostered corruption and broader oppression. On the other hand, Eertai's report differed significantly from what General Haoyulin, who was suppressing the uprising in the Tea Mountain, reported to the Emperor: “Upon investigation, it is claimed that the Tea Mountain is vast, producing no less than one million catties of Pu'er tea annually.” It is unclear whether this discrepancy was due to normal error or a decrease in tea production caused by the suppression.

Since then, the name of the Six Great Tea Mountains has become increasingly prominent. In reality, it referred more to six tea-producing regions rather than specific mountains, collectively known as the Six Great Tea Mountains.

The specific mountains included in the Six Great Tea Mountains varied at different times. For example, in 1799, Tan Cui's “Yunnan Maritime Balance Record” stated: “Pu'er tea is renowned throughout the world, and it is the product of Yunnan that provides significant economic benefits. It is produced in six tea mountains belonging to Pu'er: 1. Youle, 2. Gedeng, 3. Yibang, 4. Mangzhi, 5. Manzhuang, 6. Mansa. These mountains span 800 li, and hundreds of thousands of people enter the mountains to make tea. Tea merchants buy and transport tea to various places, making it a significant source of income.”

Later, Shifan and others held similar views, only differing slightly in the spelling of “Manzhuang” as “Manzhuan.”

In 1825, Ruan Fu's “Record of Pu'er Tea” presented two versions: the first version was as mentioned above, and the second version was: “(Simao) Prefecture has always had six tea mountains: Yibang, Jiafu, Shanxikong, Manzhuan, Gedeng, and Yiwu, which differ from the names recorded in the ‘General Records.'

After the liberation, Cao Zhongyi, the last local leader of Yibang, recalled that apart from Youle, which was managed by Cheli (now part of Jinghong City), there were five other tea mountains in Mengla. “The origin of the Five Great Tea Mountains is related to the burden of tribute and the distribution of tea plantations, forming a management system. Those under the jurisdiction of Yibang (local leader): Mansong Mountain, Man Gong Mountain, Manzhuan Mountain, Niu Gantang Half Mountain, and three and a half mountains; those under Yiwu: Yiwu Mountain and Manla Half Mountain.”

At the end of the Qing Dynasty, there was also the concept of Seven Great Tea Mountains (as seen in the major ticket of Tongxing tea products): “Pu'er tea from Yunnan is produced in seven mountains in Pu'er Prefecture: Yiwu, Yibang, Manlai, Manzong, Youluo, Manla, and Mansa.”

In summary, the Six Great Tea Mountains were a contiguous tea-producing region in the past, and thus they were also a geographical administrative region recognized by the authorities. Apart from Youle, the other five mountain regions were under the jurisdiction of two local leaders, the Yibang and Yiwu local leaders.

The specific mountains included in the Six Great Tea Mountains varied over time and were as follows:

1. Youle, Gedeng, Yibang, Mangzhi, Manzhuan, and Mansa.

2. Yibang, Jiafu, Shanxikong, Manzhuan, Gedeng, and Yiwu.

3. Mansong, Mangong, Manzhuan, Yiwu, Niu Gantang Half Mountain, Manla Half Mountain, and Youle.

The sizes of these six mountains