A few days ago, coinciding with the Shenzhen Tea Expo, a friend and I had an extensive chat about Matcha. She, somewhat forgetting her roots, mentioned that the invention of matcha demonstrated the refinement of Japanese culture. All I could do was tell her in a roundabout way that in the Song Dynasty, there was a “matcha enthusiast” who anthropomorphized twelve tea implements (a specialty of Japanese manga artists), and even gave each one an official title. Isn't that quite a leap through time?

More seriously, matcha, also known as point tea, is not only a marvel of Chinese Tea culture but was also once very popular. The practice of grinding tea leaves is said to have been inspired by the actions of Shen Nong when he chewed various herbs. Initially, however, the main methods of using tea were chewing and boiling tea blocks. By the Sui and Tang dynasties, the precursor to matcha powder—loose tea made from steamed Green Tea—began to gain popularity. Soon after, matcha was fully developed during the culturally advanced Song Dynasty and became the most popular beverage of the time. From the imperial palace to the common folk, various tea gatherings flourished. People would appraise different teas, compare tea implements, and compete in the art of preparing matcha, creating a lively scene.

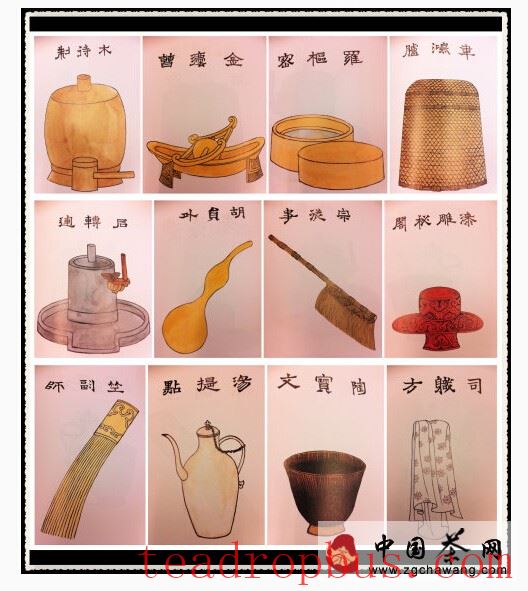

The Tea Implements Chart Praise from the late Southern Song Dynasty is a cultural gem from this “matcha golden age.” The true identity of its author, “Elder Shen'an,” remains unknown, but the creative “Twelve Gentlemen” in the book are a classic combination of Chinese Tea ceremony, Confucian culture, and entertainment for the Song scholar-official class—the twelve matcha implements were given surnames, names, courtesy names, and titles based on the Song Dynasty's official system. Here, we will list the surnames and titles of each “gentleman” in order of use and function (heating, grinding, sieving, preparing water, pouring into a cup, whisking):

First, your tea cake should be heated and dried by “Wei Honglu,” making it crisp. “Honglu” refers to the court official responsible for announcements, a pun on “roasting stove”; “Wei” represents “reed,” resembling the bamboo strips used in the roasting basket. Using a bamboo basket over the fire prevents the tea from being scorched.

At this point, “Mu Daiji” is already waiting impatiently. “Daiji” is an advisor on duty for the emperor, here referring to the wooden tea mortar used to crush the tea cake into small pieces, which are then passed to “Jin Fazao” to grind into powder. “Fazao” originally oversaw postal services but later became a judicial official, with “Cao” representing the grooves in the metal tea grinder. Subsequently, the small particles of tea need to be further ground to become sufficiently fine tea powder, which requires the assistance of “Shi Zhuanyun.” Originally a local official managing transportation and taxes, “Zhuanyun” vividly describes the use of the stone tea mill.

Once ground, don't rush to prepare the tea. “Luo Shumi” must first sift the tea powder to ensure it meets the standard. “Shumi” is a high-ranking military officer, whose meticulousness is like the small holes in a tea sieve. Additionally, any tea residue scattered on the table should not be wasted and needs to be collected by “Zong Congshi.” “Zong” refers to the fibers used to make the tea brush, while “Congshi” indicates the brush's position as an assistant to a provincial official.

After the tea has been milled, it's time to boil water. Tea connoisseurs emphasize “three boils,” controlled by “Hu Yuanwai” to manage the rolling of the hot water. “Yuanwai” originally referred to a non-regular imperial secretary but here describes the round shape of the tea ladle, made from half a gourd, hence the surname “Hu.” Hot water, referred to as “soup” in ancient times, should be poured into the “Tang Didian” soup bottle. “Didian” is a criminal justice official, symbolizing the act of “lifting the bottle and pouring water.”

The final recipient of the hot water is the tea bowl “Tao Baowen.” “Baowen” was the deputy director of the royal archives, an apt description for the beautiful patterns on a ceramic tea bowl. Before using the bowl, it should be wiped by “Sizhifang.” “Si” represents silk, while “Zhifang” refers to a handkerchief, originally denoting an official responsible for military defense in a region. A tea bowl filled with water can be hot to handle, requiring assistance from “Qidiao Migao.” “Migao” was an imperial librarian, phonetically similar to “ge,” meaning a tray to hold the tea bowl, possibly made of lacquered wood.

Finally, the grand entrance is made by the “Deputy Commander Zhu” tea whisk. “Deputy Commander” refers to the act of whisking the tea with a bamboo whisk, the most skillful step in preparing matcha. Skilled tea masters can quickly create a dense and long-lasting foam, and through a second pour or by using a tea spoon, they can create designs similar to “coffee latte art,” known as “tea hundred games.”

Having learned about the matcha skills of the “Twelve Gentlemen,” do you feel like trying your hand at it yourself? As Ming people said, “I wish to interact with the Twelve Gentlemen, tasting the finest mountain spring water, living out my life in this leisurely opulence.” For some reason, the custom of matcha was gradually replaced by steeping tea, and these twelve tea implements gave way to Teapots and teacups. When matcha became a refined “Japanese culture” and re-entered the public eye in China, I felt a bit guilty towards the “Deputy Commanders Zhu.” Matcha is not a relic; we need to keep it alive.