Are you annoyed why we've been posting about humid weather recently? Well, it's all for today's content!

Once at a Tea Expo in Guangzhou, a lady walked up to our booth, picked up the dry tea on display, smelled it, and asked, 'Why doesn't your tea have a storage smell?' Feeling proud, I waited for her compliment, but she suddenly said, 'It's not authentic Liu Bao Tea—it doesn't have a musty smell!' (What?! Did I hear that right?)

Who's been misleading our dear consumers? Step forward—I promise not to beat you up!

(By the way, Liu Bao tea doesn't have the concept of dry or wet storage. Would a 300-year-old brand not know this?)

But in the north (where the dry climate is hard to imagine, just as southerners struggle to grasp northern humidity, like the song says: 'You'll never understand my sorrow, like day can't understand night's darkness~~cut!!'), some people think our subtle aged flavor, including the iconic betel nut aroma, is musty (Betel nut aroma sighs: Blame me~).

Today, we defend Liu Bao tea's aged flavor! What's the difference between musty and aged flavors?

Aged flavor is the natural, unique aroma developed during Liu Bao tea's aging process.

(I'm Liu Bao tea—don't judge me by green tea standards. I refuse to wear a green hat!)

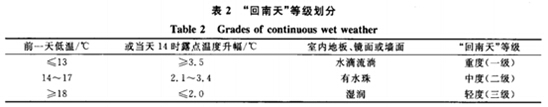

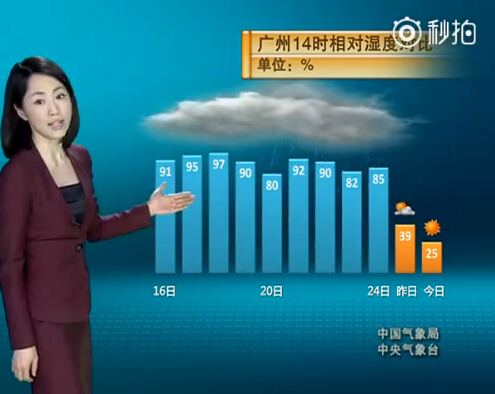

Yesterday, we explained professionally that Liu Bao tea's origin is sheltered by the Mengzhu Ridge, with its highest peak at 1,787 meters, blocking cold air and maintaining mild temperatures. Wuzhou, at the confluence of three rivers, enjoys unparalleled humidity. The annual average temperature is 19.9–21.5°C, with 78–80% humidity. In spring and winter, a sudden temperature rise of 3.5°C after cold spells brings 'humid weather,' causing walls to 'sweat.' (We repeat this to include two scientific tables omitted yesterday and to reinforce the point.)

Cited from Chen Jian, Li Jiaying, Gao Anning, Liang Weiliang, Zhao Jinbiao. 2015. Characteristics and Forecast Focus of 'Humid Weather' in Guangxi. Meteorology, 41(3)

Cited from 'Hezhou City Records': Chapter 3 — Climate and Phenology

She said: After 20+ days of rain, we finally got two sunny days—just enough for everyone to dry clothes (Wuzhou is even more humid than Guangzhou).

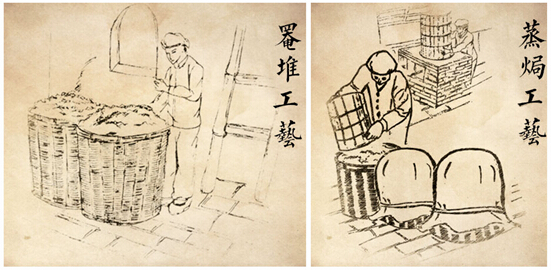

Wuzhou's environment, with its large humidity and temperature swings, fosters plants like Liu Bao tea with natural dehumidifying properties. It also aids traditional fermentation ('Yan,' 'Steam,' 'Bake') and aging.

Four Flavors Scholar • On Liu Bao

Four Flavors Scholar: Liu Bao tea fermented or aged in this climate, especially during humid weather, develops a stronger 'activity,' leading to a pronounced 'fermentation aroma.' Northerners often mistake this for 'mustiness.' It's not mold—it's normal fermentation. No reputable brand would sell moldy tea.

So, what does truly musty tea smell like?

Real musty tea has a sharp, off-putting odor—you'd recoil instantly (unless you're stubborn). It's like the stench of compost. Another trait: this smell persists from the first brew to the last, lingering unpleasantly (ew!).

Do you think mustiness comes from storage issues?

No! This persistent odor stems from 'processing': e.g., fermenting tea in a sealed, damp room to speed up fermentation, then 'airing' it. Even drying it for millennia won't help!

Professor Cai Zheng'an from Hunan Agricultural University summarized it succinctly:

Raw materials are the foundation,

Processing is the key,

Aging is the升华.

Thus, our ancestors followed ancient wisdom: 'Follow yin-yang, harmonize with techniques.' They used traditional 'Yan,' 'Steam,' and 'Bake' fermentation, then aged the tea in Wuzhou's unique climate. Historical records show Guang Sheng Xiang soaked wooden planks in tea to make storage barrels for mellow teas.

300+ years of traditional 'Yan,' 'Steam,' 'Bake' techniques—potent tea with strong dehumidifying effects.

Q: But what if I dislike this 'fermentation aroma' yet want the dehumidifying benefits?

Five words float by: Not a problem!

No need to ask Four Flavors Scholar—here's the answer: Unpack the tea (no need to air it), and in a few days (or hours in some places), the smell fades without losing potency. Or skip the first 2–3 brews—the aroma disappears afterward.

By the 15th brew, sniff the leaves—that fresh plant scent is divine! Pass the rice!

Traditional Liu Bao tea is versatile: boil, steep, or brew—simple and satisfying.

Summary

Everything in nature 'dies,' rots, and attracts microbes that feast and excrete 'waste.' Hence, spoiled things smell foul—nature's way of warning us. But ancient wisdom revived tea through fermentation ('Yan,' 'Steam,' 'Bake'), giving it a second life. Aging under Wuzhou's climate preserves its herbal aroma, offering both pleasure and health benefits.

'Everything is medicine; treasures abound.' But we must respect and harmonize with nature—defying it invites ruin.