For most Chinese people, tea is a delicacy and a cultural symbol. However, in the long river of history, tea has repeatedly acted as a trigger for wars. The reason lies in the idea of "using tea to control foreign tribes," which was a consistent strategy of Central Plains dynasties since the Tang and Song periods, reaching its peak in the Ming Dynasty. The Qing Dynasty merely inherited this governance philosophy.

The consensus on "using tea to control foreign tribes" was built on a broad foundation. The American scholar Morse, who studied China's foreign relations, reiterated this popular notion in his work The International Relations of the Chinese Empire: "There has always been a belief among the Chinese that tea and rhubarb are necessities for the West, and only China can supply tea and most of the rhubarb." This contradiction finally emerged during the Ming Dynasty, when capitalism began to sprout. The Ming fought a war with no victor over tea, while the late Qing Dynasty declined due to tea.

From a historical perspective, tea has never been merely a good thing for self-cultivation.

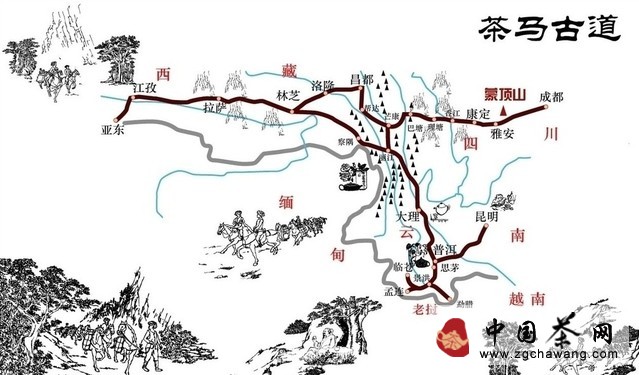

Tea's importance lay in its role as a strategic resource. During the Song Dynasty, tea was closely linked to warhorses. By then, the Central Plains dynasties had lost control over northern grasslands and regions like Hetao, which were suitable for horse breeding. This meant that obtaining warhorses could only be achieved through trade with horse-producing ethnic groups.

So, what did the Central Plains have that could interest these minority groups?

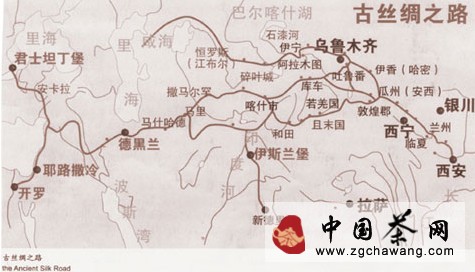

The famous Silk Road served as a bridge for trade between East and West. The main goods transported along this route—silk, cotton, tea, and porcelain—were all specialties of the Central Plains. Tea, undoubtedly, was more suitable than other items for exchanging warhorses. More importantly, tea was a crop unique to Central Plains civilization. The northern minority regions were entirely unsuitable for tea cultivation. Thus, tea became a weapon used by Central Plains dynasties to manage or control northern nomadic tribes.

Shortly after the Wanli Emperor ascended the throne, Chief Grand Secretary Zhang Juzheng issued an edict in the emperor's name, ordering the closure of border trade. The Ming Dynasty's intention was to strictly crack down on private tea merchants and punish corrupt officials while shutting down the border tea markets. However, these severe measures completely cut off the supply of tea through border trade.

The Mongol and Jurchen tribes in the north immediately fell into chaos, petitioning the Ming Dynasty to reopen border tea trade. Yet the response was a firm refusal.

A war triggered by tea finally erupted. The conflict lasted three years, with no clear victor. The Mongol tribes suffered heavy casualties, and although the Ming army ultimately defended Qinghe Fort, their commander Pei Chengzu died in battle, with countless soldiers and civilians killed or wounded...

Such wars provoked by the interruption of tea trade were not uncommon in Chinese history. Unlike tea-drinking habits in other regions, tea consumption among northern ethnic groups was a physiological necessity. The diets of nomadic peoples like the Mongols consisted largely of greasy, hard-to-digest foods such as beef, mutton, and dairy. Tea, rich in vitamins, tannic acid, theophylline, and other nutrients lacking in fruits and vegetables, provided essential supplementation. The abundant aromatic oils in tea could dissolve animal fats, reduce cholesterol, and strengthen blood vessel walls. The functions of tea perfectly compensated for the deficiencies in the nomadic diet.

Therefore, while tea was a lifestyle调剂品 for the Central Plains people, for northern minority groups, it became a daily necessity like grain and salt. Cutting off the tea supply almost severed their lifeline.

Around the time of the Opium War in 1840, tea was not only a passport for the late Qing Dynasty to engage with the world but also one of the most thoroughly globalized trade commodities. It was such hard currency that enabled the late Qing to establish its place in the world and attract global traders.

By monopolizing China's tea trade, the British East India Company became the world's largest corporation and a synonym for Britain itself. By 1718, tea had replaced raw silk and textiles as the top product exported by the East India Company from China. The tea trade was vital not only to the company's survival but also to British government revenue.

Some argue that, economically, the Opium War was essentially a tea war. The initial issue stemmed from the trade deficit caused by tea imports to Britain. To reverse this deficit, Britain began exporting opium to China. Thus, tea was the cause, and opium the effect. The influx of opium led to a massive outflow of Chinese silver, prompting the anti-opium movement. The cycle of tea, silver, and opium ultimately triggered the Opium War.

From 1867 to 1894, even with Britain's massive opium imports, China's tea export value balanced its import value. Tea prices were entirely determined by China.

However, as the British began successful tea cultivation experiments in India, tea was no longer exclusive to China. The invisible Great Wall of tea collapsed almost instantly. Subsequently, as Japanese tea gained prominence in the international market and even re-exported to China, China lost its trade and discursive power over tea, becoming a mere spectator...

Anthropologist Alan Macfarlane, in Green Gold, argues that tea created Britain and enabled it to become the world's largest empire. He believes that the origins of the British Industrial Revolution are closely linked to tea.