Tea Collection (Part 1)

China is the homeland of tea, with a history that can be traced back to the "Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors." Today, tea is not only for drinking; some types can also be stored and collected. In fact, collecting tea is similar to collecting wine—it preserves value while reflecting personal taste. In recent years, it has gradually gained recognition and popularity among many collectors. The prices of new teas have surged, and aged teas naturally follow suit. In reality, tea collections can appreciate by about 30% annually, making them highly favored by collectors.

The Yunnan horse caravan's arrival in Beijing sparked a Pu-erh tea craze. Regardless of subsequent praise or criticism, years later, Pu-erh tea, a drinkable "antique," has become the primary form of tea collection. However, as Pu-erh tea enters thousands of households, how much do we truly understand about it? How much do people know about collectible teas? With this in mind, what other teas can be collected?

Before understanding collectible teas,

let’s first explore the prices of tea collections.

Every year, tea prices rise due to increasing costs, especially this year. In some major tea-producing regions like Yunnan and Guangxi, persistent low-temperature and snowy weather delayed the arrival of some tea products by nearly half a month. This intensified the pressure on tea merchants and factories to集中采茶, leading to a nearly 20% increase in labor costs. Industry insiders expect tea prices to generally rise by 5%-10%. However, the emergence of sky-high tea prices seems unrelated to production costs and more like an investment operation.

From a market perspective, 500 grams for 180,000 or 130,000 yuan is not particularly astonishing, as teas priced above 30,000 yuan per 500 grams are quite common. Especially during the peak of Pu-erh tea speculation in previous years, prices of over 1 million yuan per 500 grams have appeared. A Southern Metropolis Daily reporter visited multiple tea shops in Nanshan and Luohu and found that a beautifully packaged 150-gram Longjing tea was priced at 12,000 yuan, equivalent to 38,000 yuan per 500 grams. A well-known chain tea institution in Shenzhen offered an aged Pu-erh tea, 1,400 grams for 80,000 yuan, equivalent to 29,000 yuan per 500 grams. Teas priced between 3,000 and 10,000 yuan per 500 grams are even more widespread.

*Excerpted from "Beijing Daily"

Not All "Cakes" Are Worth Collecting

Mr. Zhengyan believes that raw Pu-erh tea cakes, charcoal-roasted rock tea, and some black teas are suitable for collection. I personally prefer rock tea, as discussed in previous articles. During the Song Dynasty, there were "Dragon and Phoenix Cakes"; in the Qing Dynasty, "Wuyi Tea Bricks"; and today, there are "Rock Tea Da Hong Pao Tea Bricks."

This issue focuses on Pu-erh tea...

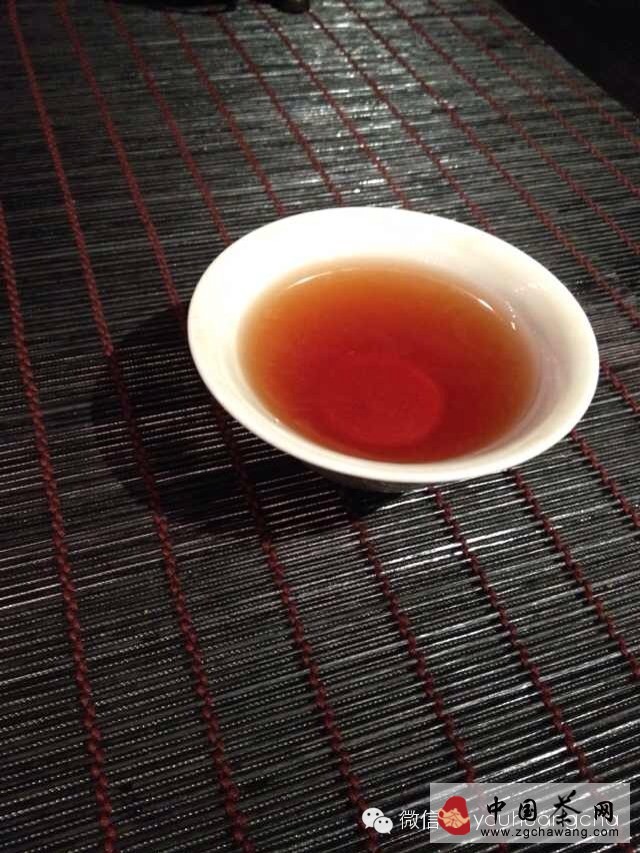

Some people appreciate the color, aroma, and taste of good tea, while others are familiar with the health benefits of aged tea. But what exactly defines good tea? Is there a unified standard for good tea? Does Pu-erh tea improve with age? This requires an understanding of the era classification of Pu-erh tea.

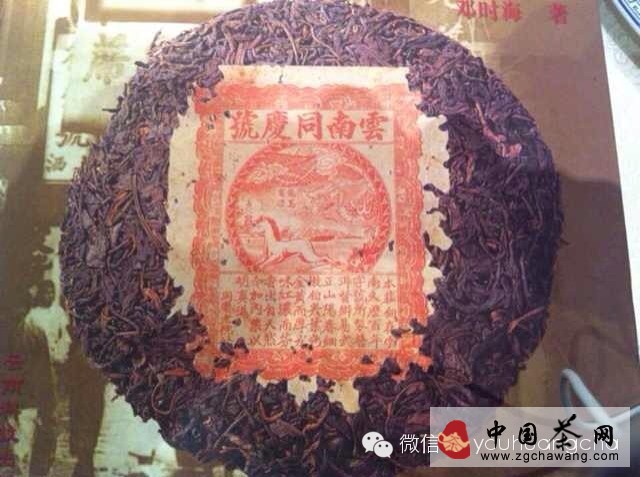

In tea history, teas produced from the opening of the Pu-erh Prefecture Tongqing Tea House in 1733 to the founding of New China are referred to as "Haoji Tea." Today, tea cake collections generally regard 1733 as the upper limit. Teas before this, so-called high-antiquity teas, have largely exited market circulation. Haoji Tea was managed by old-established tea houses and characterized by: raw materials from arbor trees, seed-planted tea trees without grafting, and no mixing of other tea varieties during production. The quality of tea cakes depends on botany, production techniques, circulation packaging, and storage processes. Botanical attributes ensure the quality of raw materials. Tea trees are divided into arbor and shrub types, with seed-grown and grafted varieties. Each seed-grown arbor tea tree has a unique flavor, with strong disease resistance, pest resistance, and infection resistance. In contrast, grafted or layered Pu-erh tea not only lacks the rich flavor of seed-grown arbor tea but also has the drawback of species degradation. Additionally, the absence of chemical pollutants like fertilizers and pesticides ensured the pure and rich taste of Haoji Tea. Due to entirely traditional manual production techniques,优质 soil, and climatic conditions, Haoji Tea became the "nobility" of Pu-erh tea.

By the early 1970s, large-scale blending began, and teas from this period are known as "Yinji Tea." During this time, state-owned tea factories replaced old tea houses. Tea cakes were packaged in paper printed with the word "tea." Although methods were no longer traditional, the raw materials still came from seed-grown Pu-erh trees, and careful selection and meticulous production maintained a relatively high overall standard, making Yinji Tea the "golden collar" of Pu-erh tea.

With the large-scale promotion of grafted tea, Pu-erh tea raw materials entered an unprecedented new era. Marked by the formal establishment of the China National Native Produce & Animal By-Products Import & Export Corporation Yunnan Branch in 1972, the large-scale blending method pioneered by the "Seven Sons Small Yellow Mark" gradually became mainstream, altering ancient production methods. Tea products from this period were printed with "Yunnan Seven Sons Cake" and are referred to as "Qizi Bing Tea," becoming the "white-collar workers" of Pu-erh tea. This period lasted until around 1992.

In the subsequent period, the use of fertilizers and pesticides in tea gardens affected raw material quality. The emergence of large-scale counterfeiting further compromised tea purity. Driven by profit, people pursued yield, leading to overly dense tea tree planting and soil degradation, severely reducing Pu-erh tea raw material quality. A more serious phenomenon was the bulk purchase of non-local teas and their blending into Pu-erh tea cakes, facilitated by logistics development. Tea products from this period have almost no collection value.

Entering the 21st century, some tea enthusiasts who had tasted traditional Pu-erh could not tolerate the poor quality of contemporary teas. They began personally cultivating, harvesting, and producing teas using traditional methods, using seed-grown ancient and large trees, ushering in a new phase of high-quality tea products.